How Congress Can Engage the American Public on Foreign Policy

Legislators should consider strategies to boost congressional influence as they craft public-facing messages about foreign affairs.

This piece is adapted for Lawfare from a memo submitted as part of the following Bridging the Gap & Library of Congress workshop, which took place on Dec. 13, 2024:“Strengthening the Role of Congress in Foreign Policy: A New Voices in National Security Workshop,” sponsored by Bridging the Gap and The John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress.

In early 1965, James Reston of the New York Times embarked on a 2,000-mile journey through the American South and mid-Atlantic to assess public sentiment toward the Vietnam War. Reston concluded that despite shifts in the government’s approach to the war, the American public was disinterested, uncertain, and seemed to hold a “mood of acquiescence.”

Reston largely blamed Congress. He judged that the institution “never really debated fully” the premises of the war and concluded that the public was dispassionate toward Vietnam at least in part “because even the major questions have not been debated in an orderly manner” by the legislature. As a remedy, Reston presciently suggested that “the Congress, or its appropriate committees, could reexamine the policy.” To stir the public on a war that would become one of America’s greatest foreign policy disasters, in this journalist’s view, Congress had to engage. Indeed, Sen J. William Fulbright’s subsequent public-facing hearings that revealed the executive branch misrepresentations about the war’s progress are often credited with turning the tide of public opinion against the war, and ultimately facilitating its cessation.

Half a century later, President Trump’s striking foreign policy maneuvers—including sending migrants to third-party countries, halting foreign aid, enacting tariffs against allies, freezing and then restarting support for Ukraine, bombing Iran, intimidating Greenland and Panama, and more—have so far spurred little formal congressional resistance. Republicans enjoy majority status in both chambers and in turn control the constitutionally allocated policymaking tools of the institution. Due to Republicans’ institutional control as well as their powerful partisan incentives against challenging the president, Congress has remained largely uninvolved as Trump redesigns U.S. foreign policy through executive orders.

However, Congress has a series of informal tools at its disposal to shape foreign policy. Although a Republican-dominated Congress wouldn’t permit serious investigations into Trump’s foreign policy conduct, Fulbright’s Vietnam hearings illustrate a broader point: Congressional engagement with the American public can mold foreign policy. Congressional messaging on foreign affairs issues is consequential because it can shape public opinion, influencing the contours of U.S. foreign policy in the long run. Crucially, speaking up on foreign policy is relatively straightforward. Unlike formal tools, issuing a message does not require holding majority status, or achieving constitutionally allocated levels of consensus. Any legislator, at any time, can make a compelling statement on a foreign relations issue. And these statements can matter.

How, then, should legislators shape their messaging about foreign policy? Three strategies of congressional public engagement may be both actionable and useful.

Strength in Numbers

While individual statements are important and worthwhile, legislators can accomplish more in foreign policy messaging collectively. Joint statements, even if issued by only a handful of legislators, can be both powerful and politically viable.

Bipartisan messaging on foreign policy is useful because it can be particularly persuasive to both Democratic and Republican audiences. When some endorsers have military or other foreign policy experience, this messaging can be even more compelling; legislators with this kind of experience are perceived by Americans of both parties as more likely to have expertise on foreign policy issues, boosting their credibility. Sens. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and John Kerry (D-Mass.), for example, were thought to have been important foreign policy voices within their parties precisely because of their significant military experience. When possible, then, legislators without significant foreign policy experience should consider issuing joint statements with those who do possess such experience.

Unsurprisingly, however, legislators do not often publicly criticize the foreign policies of presidents of their own party, as doing so can risk retaliation from a sitting administration. President Trump, for example, has not been shy about retaliating against Republicans who criticize him; this has likely chilled intraparty resistance across a range of issues. Trump is not the first president to crack down on and prevent criticism from his own party, nor will he be the last.

In-party hesitancy to criticize a president, unfortunately, can seriously undermine congressional influence in foreign policy. In-party legislators are often best positioned to exert costly oversight against a sitting president because their criticism receives outsized media attention, and is more likely to be seen as credible. Indeed, some of the most important episodes of congressional oversight on foreign policy feature legislators who publicly broke with presidents of their own party. Consider Fulbright’s opposition to Vietnam, flagged above.

Consider, also, Republican Sen. Charles Sumner’s individual opposition to his fellow Republican President Ulysses S. Grant’s proposed annexation of the Dominican Republic. As the United States stitched itself back together in the years following the Civil War, President Grant looked abroad for solutions to challenges posed by Reconstruction at home. He pushed to annex San Domingo, today known as the Dominican Republic, at least in part because he believed it could accommodate the emigration of Black Americans in the South. The particular merits of this proposal aside, it ultimately failed at least in part due to in-party opposition: On March 24, 1870, Sumner delivered a four-hour floor speech in Congress opposing Grant’s plan that received prominent coverage in the New York Times. The historian Joan Waugh observed that Grant’s proposed annexation failed following Sumner’s speech because “public opinion had turned against the treaty, and the issue disappeared from public debate.” Sumner’s individual opposition, which moved the American public, is thought to have been a crucial roadblock.

Joint statements may help with this co-partisan dilemma, providing some political cover for in-party legislators who participate. Legislators likely find it politically easier to break with an in-party president (or support the policy of an out-party president) if many of their fellow partisans do it with them.

Policy, Not President

Evidence suggests that foreign policy messaging on the substance of the policy, not on the president who implements it, is more likely to be effective. Since at least World War II, however, there has been a trend away from substance and toward the personalization of foreign policy, with legislators invoking the executive in their foreign policy communications to serve partisan aims.

Specifically, presidential co-partisans in Congress reference the president when they praise foreign policy and avoid referencing the president when they voice hesitation. Out-party legislators, for their part, reference the president when they attack the policy and avoid naming the president when expressing some support for the maneuver. Legislators who share partisanship with a sitting president can benefit politically from tying foreign policy praise to the president, just as out-party legislators can benefit by explicitly attaching criticism.

Republicans, for example, often attacked President Biden’s 2021 withdrawal from Afghanistan in personal terms, directly referencing him as the architect of a foreign policy disaster. Those who preferred a drawdown—if they spoke up at all—were less likely to cue Biden. Many Democrats similarly referenced Biden by name in their earlier commentary praising his decision to end the longest war in American history. Democrats who publicly criticized the withdrawal’s execution, however, were less likely to tie it to their co-partisan president.

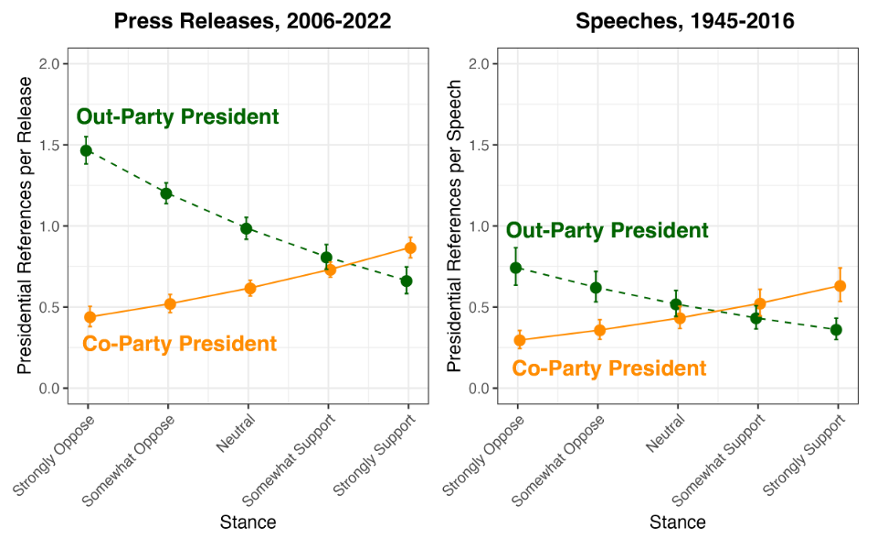

This pattern has recurred across the modern history of U.S. foreign relations. Figure 1 shows the relationship between the expressed stance of a legislator’s foreign policy messaging, partisanship, and the predicted number of presidential references in the legislator’s message. To construct this estimate, I assembled a new list of just over 100 major U.S. uses of force and diplomatic initiatives spanning 1945-2022, collected plausibly relevant legislator press releases and floor speeches, and used computational techniques to determine the message stance and whether or not the message references the sitting president by name. For more information on these particular estimates (and for an explanation of broader patterns of congressional messaging and American public opinion on foreign relations), see my 2025 dissertation here.

Figure 1. Predicted presidential references in foreign policy messaging by stance and partisanship.

The topline takeaway is that the more presidential co-partisans in Congress praise foreign policy, the more they explicitly associate it with a sitting president. Out-partisans, conversely, increasingly invoke a president as they increasingly attack their foreign policy. Naming a president explicitly associates policy criticism or praise with the administration.

But this personalization of foreign policy presents meaningful trade-offs. By explicitly contributing to partisan conflict, it can reduce the feasibility of a joint statement. (To be sure, Democrats would have hesitated to sign on to a statement that explicitly bashed Biden just as Republicans would have hesitated to join one that heaped direct praise onto the administration.) Personalizing a foreign policy also shapes how Americans interpret the legislator’s statement. All else equal, presidential co-partisans reflexively become more supportive of the policy just as presidential out-partisans become more opposed.

Moreover, this form of partisan framing can reduce informational takeaway. The public tends to recall less news content overall when information is presented in a partisan way.

This particular finding raises the broader question of what productive, substantive congressional debate on foreign relations and other important issues looks like in practice. After all, James Madison (often dubbed the ‘“father” of the Constitution) envisioned Congress as the locus of reasoned government deliberation on national policy. Philip Wallach wrestles with these issues at length in a remarkable treatment of why we need Congress, what the institution can be at its best, and the ways in which it has fallen short of that ideal.

Here, I make a narrower contention that may inform that broader discussion: Legislators who want to maximize reach across partisan lines and substantive recall of their commentary might focus their statements on the merits or failings of a particular policy, not on the strengths or weaknesses of the president who crafted it.

Move First and Persist

Congress is usually broadly reactive to presidential foreign policy maneuvers. The majority of legislators—if they do take a stance on a particular foreign policy issue—wait until the president has announced or has begun to implement a particular policy.

This reactive position-taking is important to public opinion formation and shaping policy over the long run. But position-taking could be even more powerful if initiated earlier in the process—perhaps right at the outset of an international crisis and before a president has clearly staked out a position.

Legislative messaging about what the United States should do in foreign policy can be most persuasive to the public early on, as undecided Americans look to make sense of still undefined issues. Early messaging can also constrain presidents by increasing the political risk of using force. Examples where congressional reticence regarding a prospective use of force plausibly prevented it include Dien Bien Phu (1954), the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis (1958), the Six-Day War (1967), Iran weapons of mass destruction (WMD) (2007), and Syria WMD (2013), among many others.

Congressional hawkishness can also push presidents to take action despite hesitations. During the Cuban missile crisis, for example, President Kennedy decided to escalate toward the brink at least in part due to public-facing congressional hawkishness. Thus, while early messaging can amplify congressional influence, it may not always lead to normatively better outcomes. But it is a useful legislative tool.

Even after the initial stages of a foreign policy crisis have passed, legislators should continue to engage the public about them. Public attention to major foreign policy issues often hinges on sustained congressional engagement. This continued engagement, over time, can generate pressures on presidents to adjust policy in Congress’s preferred direction.

Legislators’ collective failure to raise public awareness of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, for example, made it politically feasible for the Clinton administration to look the other way. And important moderate Democrats’ equivocation during the early stages of Israel’s war in Gaza perhaps facilitated President Biden’s uncritical embrace of the humanitarian suffering that the nation has inflicted. Mainstream Senate Democrats have only recently adopted a reportedly “major shift in tone,” denouncing Israeli human rights violations.

Today, this congressional mandate is no less pressing. While public engagement on foreign policy in Congress is an informal and indirect tool of influence, it can nevertheless be consequential. Legislators who wish to play a larger role in foreign policy should seize the initiative in their public messaging, even if formal actions remain out of reach. Taken together, these three accessible and politically viable messaging approaches—strength in numbers; policy, not president; and move first and persist—might help legislators amplify their influence over public opinion and, in turn, over U.S. foreign policy.