How to Resolve a Contested Election, Part 3: When Elections Fail

In the most desperate scenarios, the voters may not be the ones who decide who becomes president after all.

This post is part three of a three-part series on the legal process for selecting a president and the possibility of a contested 2020 election. Anderson will be discussing these articles and answering questions from Lawfare patrons at a Lawfare Live online eventthis Friday, Oct. 23, at 12:00 noon EDT. For more information on how to join, click here.

The first two posts in this series covered the presidential selection process more or less as it’s intended to work. The states elect (or appoint) individual electors pursuant to state law, who in turn cast electoral votes for president on their behalf. Congress then receives and—once the newly elected Congress is able to sit and compose itself—counts these electoral votes to determine the winner of the election, resolving disputes along the way. Whichever candidate receives votes from a majority of the electors appointed becomes president, and his or her running mate becomes vice president.

But what happens if no candidate secures the support of a majority of electors? Or if this process breaks down, as a result of either good-faith disagreement among the participants or deliberate obstruction by key officials? This post takes up these last two important questions. The answer to the first is a special constitutional process called a contingent election. And the answer to the latter is a law called the Presidential Succession Act. Neither, however, is straightforward.

Contingent Elections

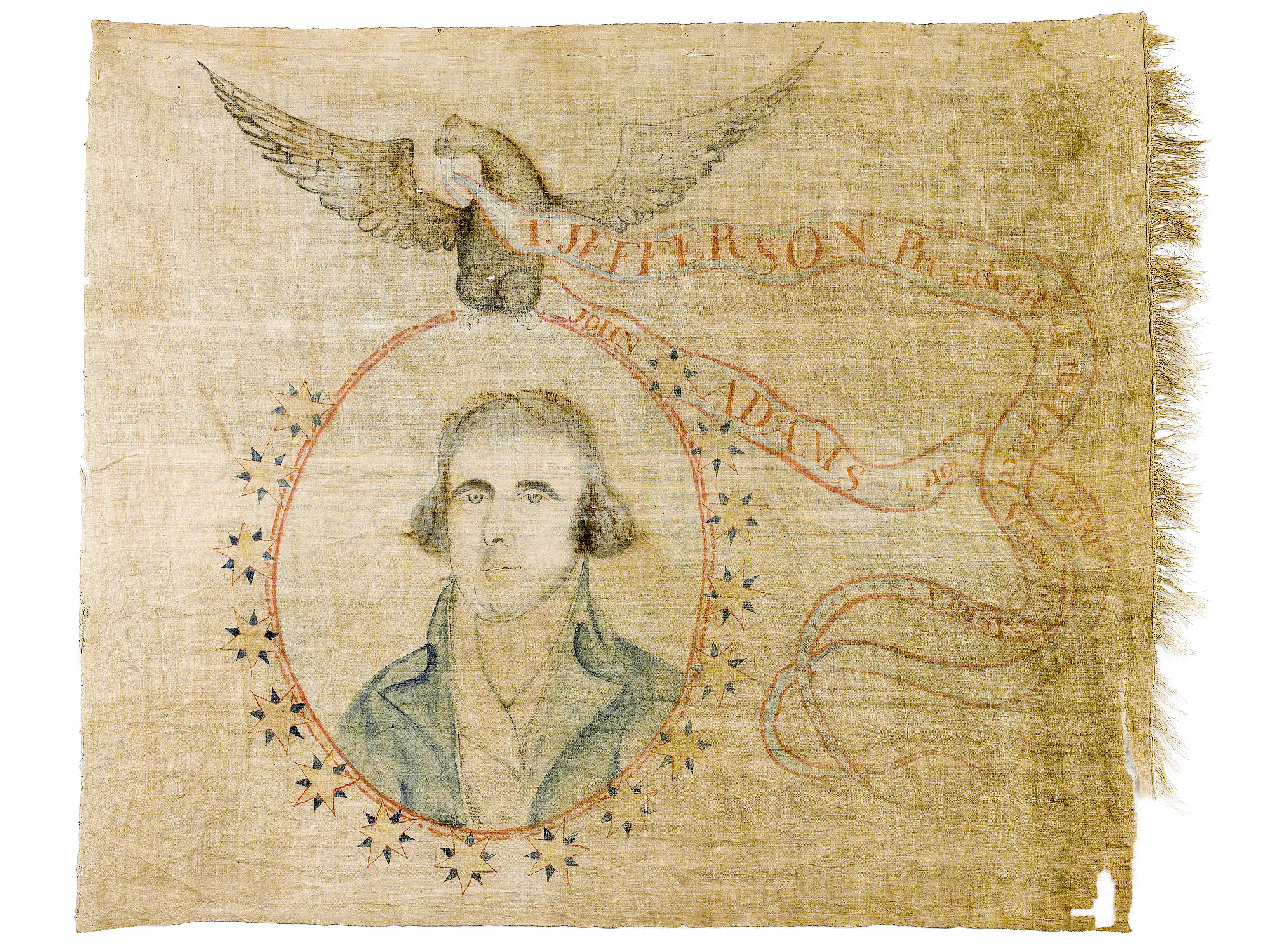

Those who have seen the musical “Hamilton” are likely to be familiar with the concept of a contingent election. In 1800, a tie vote between Aaron Burr and Thomas Jefferson in the Electoral College threw the presidential contest into the House of Representatives, where Alexander Hamilton successfully lobbied on the behalf of Jefferson. Following the Burr-Jefferson contest, the process for resolving a tie was amended by the 12th Amendment in 1804. This revised process has been used only twice since—to elect a president in 1825 and a vice president in 1837—leaving a paucity of useful precedents for how such proceedings should operate.

The 12th Amendment states that, if no candidate receives the majority of electoral votes needed to be president, then the House “shall choose immediately, by ballot, the President” from among the three candidates who received the most electoral votes. This echoes the original language in Article II of the Constitution—superseded by the 12th Amendment—which required that the House “immediately chuse by Ballot one of [the candidates] for President” among those who received the most electoral votes. The House seems to have adhered to a literal interpretation of these requirements in 1801 and in 1825: It entered deliberations directly from the joint session for counting electoral votes without considering other business, and used written paper ballots submitted in secret. Members of Congress do not each submit their own votes, however. The 12th Amendment indicates that members’ votes are to “be taken by states, the representation from each state having one vote[,]” with each state delegation receiving a single vote. In 1801 and 1825, the House executed this unorthodox process through a two-tier voting system, through which each state delegation decided its vote internally on a majority basis and then cast a unified second ballot on that basis as a delegation. The 12th Amendment requires that at least one member from only two-thirds of the states be present to establish a quorum for this process but demands that a candidate receive the support of a majority of all states in order to be elected president. The District of Columbia has no vote and plays no part in this process, despite having been granted electoral votes by the 23rd Amendment.

While the House resolves any tied count among presidential candidates in the Electoral College, any tie between vice presidential candidates goes to the Senate. The Senate has used this process once, in 1837. During that contest, the Senate entered into the process directly from the joint session for counting electoral votes, even though the 12th Amendment doesn’t require that this process be started “immediately.” Unlike their House counterparts, senators are free to vote individually, with two-thirds necessary for quorum but support from a majority of all senators necessary to become the new vice president.

The rules governing these sessions are not addressed by the Electoral Count Act or other provisions of federal law and are instead left largely up to the House and the Senate. In 1825, the House managed its proceedings by forming a special select committee composed of a representative from each state that settled on the applicable rules, including meeting in closed session and requiring that motions be made and seconded by state delegations, not individual members. By contrast, the 1837 proceedings in the Senate appear to have been conducted by the conventional rules applying to proceedings in that chamber; the matter of who became vice president was ultimately resolved in short order by voice vote. The modern House and Senate would presumably not be bound by these precedents if a contingent election were to arise today but, instead, would be similarly empowered to select their own rules.

Contingent elections are democratic only in an imperfect and indirect sense. Because each state has an equal number of votes in a contingent election, regardless of population, the process inherently gives greater weight to states with lower populations and disfavors those with higher populations and denser urban areas. As a result, there is a substantial chance that the outcome of a contingent election would depart from the popular vote.

In 2020, this weighting strongly favors the Republican Party: 26 state delegations in the House are currently controlled by Republicans, though Democrats make up a majority of members in the chamber. As Nate Silver discussed recently on FiveThirtyEight.com’s “Model Talk” podcast, current projections for the 2020 vote suggest that, while there is about an equal chance that either party will control a majority of delegations come 2021, the most likely scenario is an even split. Any disputed congressional elections would also figure into this math: For example, members-elect whose seats are in the middle of an election dispute could throw control of a given state delegation in one direction or another, even if they later prove to have lost the election. Of course, that depends on whether the supposed member-elect would be able to fill the seat in the first place with a dispute ongoing. And this is where continued Democratic control of the House is important, because a Democratic Party that holds onto its majority could have substantial control over who fills a seat during a dispute. Needless to say, if it begins to look like a 2020 election will come down to a contingent election, a great deal of partisan jockeying around House seats is almost certain to ensue.

When it comes to selecting a new president, the contingent election process is more or less the end of the road—which is not necessarily a reassuring prospect. In 1801, it took the House more than 30 ballots over the course of almost a week to select a president. A future House may well be even more evenly divided among the three candidates it is permitted to consider. This could result in enduring gridlock—a paralysis that may well extend past the two weeks between the counting of electors and the beginning of the next presidential administration.

Presidential Succession

The 20th Amendment makes one thing crystal clear: Regardless of the results of the most recent election, the terms of the incumbent president and vice president end at noon on Jan. 20, unequivocally and without question. By this point in 2021, Donald Trump will, unless reelected, no longer be president. But if the electoral votes are still being counted or contingent election procedures are still being pursued—or if both have resulted in stalemate—who becomes president?

The amendment itself—adopted in 1933 to reduce the postelection lame duck periods and give newly elected congresses, rather than incumbent congresses, the central role in deciding presidential election disputes—provides the first answer. It states that “[i]f a President shall not have been chosen before the time fixed for the beginning of a new term[,] ... the Vice President elect shall act as President until a President shall have qualified.” After all, even if the House is deadlocked in a contingent election, the Senate may have had more luck selecting a new vice president. If no vice president has been selected either, however, then the 20th Amendment says that “Congress may by law provide” an appropriate remedy for selecting an acting president, who will fill that role until a president or vice president is qualified. In many ways, this parallels the original language on succession in Article II of the Constitution, which holds that “Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President[,]” but does not specifically authorize Congress to address vacancies arising from a failed or stalled electoral process.

Congress appears to have used this authority when it enacted the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, now codified at 3 U.S.C. § 19. The law expressly covers situations where “there is neither a President nor Vice President” by reason of “failure to qualify.” While some observers have questioned whether this would necessarily apply to all of the doomsday scenarios that might emerge from the 2020 election, the law would clearly seem to cover an outcome where the electoral vote counting or contingent election process is inconclusive or still ongoing when the offices of president and vice president suddenly become vacant at 12:01 p.m. on Jan. 20.

Under the act, the first contingency in such circumstances would be for the newly elected speaker of the House to become president as soon as he or she resigns from Congress. If there is no speaker—an outside possibility if electoral disputes truly derail the entirety of the 2020 elections—then the presidency passes to the president pro tempore of the Senate, an elected position traditionally given to the most senior senator of the majority party on the same conditions. The same is true if the speaker of the House is ineligible for the presidency—for example, if he or she is not a U.S. citizen or 35 years old or, perhaps, declines to resign from the role of speaker. In both cases, the individual appointed serves as acting president until a qualified and competent president or vice president emerges—or, if that never happens, until the end of the current presidential term.

If neither the speaker of the House nor the president pro tempore is available and qualified, then the Presidential Succession Act turns to another set of officials: the cabinet, or at least those members who have been “appointed, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate,” prior to the vacancy. (This provision leaves it unclear whether cabinet officials who received Senate advice and consent for another position and are serving on the cabinet in an acting capacity—a common phenomenon in the Trump administration—are eligible.) In this case, this would almost certainly be the incumbent cabinet of the Trump administration, because cabinet officials’ terms in office do not automatically end with the presidential term. Instead, cabinet officials continue in their roles until they resign or are removed by the president.

The Presidential Succession Act establishes a sequence in which these officials will fill the presidency if available and qualified, based on seniority: The secretary of state is first, then the secretary of the treasury, secretary of defense and attorney general, followed by the remainder of the cabinet until the most recent addition, the secretary of homeland security. Whoever ultimately takes on the role of acting president automatically resigns from their cabinet role as soon as they take the requisite oath of office. If a speaker of the House or president pro tempore of the Senate becomes qualified and eligible during the cabinet member’s time as acting president, then the speaker or president pro tempore will supplant the cabinet official in question as chief executive.

Some constitutional doubt surrounds the Presidential Succession Act, as Jack Goldsmith and Ben Miller-Gootnick have written. Scholars have argued that the presidency is limited to members of the executive branch under Article II, which states that Congress may “declar[e] what Officer” inherits the role—a term usually used in the Constitution to refer to officials within the executive branch, meaning that Congress cannot constitutionally pass the presidency to the speaker or president pro tempore. This view has been a minority one since the first Congress, which installed legislative officers in its original line of presidential succession. Nonetheless, it has always had adherents and continues to carry substantial weight among contemporary lawyers who tend to see the Constitution as requiring a sharp separation between the political branches—a community that includes Attorney General William Barr, who will most likely still be in office on Jan. 20 if he has not resigned or been removed.

But the situation is arguably different when it comes to the Presidential Succession Act’s provisions governing what happens when every candidate “fail[s] to qualify” for the offices of president and vice president. Article II isn’t what gives Congress the authority to address such circumstances. The 20th Amendment provides that authority—and it uses the term “person[s]” to identify who may serve as acting president, not “Officer[s]”. This suggests that the universe of people who may be made acting president pursuant to the 20th Amendment may well be less limited than those who may be made acting president in the scenarios covered by Article II, even if the word “Officers” refers only to those within the executive branch. Consistent with this view, the 20th Amendment elsewhere gives Congress the authority to determine which “persons” may fill vacant candidacies for president and vice president if the original candidates were to die before a contingent election could be performed. Certainly the authors did not mean for these appointments to be limited to incumbent cabinet officials, who may well be from a different party or have little to no relationship to the deceased candidate or his supporters. This in turn suggests that the 20th Amendment’s use of “persons” was not intended to be limited to members of the president’s cabinet.

Such an arrangement would make some structural sense as well. The cases of removal, death, resignation, and inability addressed by Article II can all occur in the middle of a presidential term, when the mandate from a prior election remains intact. Handing the presidency over to a legislative official who may represent a different party would arguably upset the intent of the voters, which is why Article II may favor keeping the presidency within the executive branch in those circumstances. But in the situations addressed by the 20th Amendment, the prior presidential administration’s term has fully ended. Instead of remaining true to an electoral mandate, limiting Congress to current cabinet officials might prolong the time in office of an administration that was just rejected (or at least was not clearly reelected) by the voters. In this scenario, it makes sense that the authors of the 20th Amendment might have wanted to provide Congress with the authority to place a broader range of individuals in the line of presidential succession that they had under Article II. As a result, even if the Presidential Succession Act’s placement of the speaker and president pro tempore in the line of succession could be unconstitutional in cases of presidential death or resignation, these provisions may be constitutional when applied in cases where the election process fails to make a choice by the appointed time.

Nonetheless, some adherents to a strict vision of the separation of powers have persisted in the view that the speaker of the House and president pro tempore can never serve as acting president—and it’s entirely possible that Barr will share this view, as a matter of either good faith or political convenience. As Goldsmith and Miller-Gootnick describe, this could result in a scenario where Barr—whose legal views as attorney general are normally binding on the executive branch unless superseded by the president—issues a legal opinion recognizing Secretary of State Mike Pompeo as acting president, even while the speaker or president pro tempore lay claim to the office themselves.

How this standoff might be resolved is not entirely clear, though incumbent Trump administration officials are likely to have an edge in creating “facts on the ground” when it comes to who exercises control over the executive branch. At a minimum, the issue seems likely to involve substantial litigation, which may take days if not weeks to resolve and could bring into question the validity of any actions pursued by whoever holds the position of acting president. Some observers have even suggested that the courts may consider the issue a political question and decline to resolve it, though the Supreme Court has proved bullish on its duty to address the constitutionality of statutes in more recent cases. Regardless, until the issue is resolved by the judiciary—or the relevant parties reach some sort of compromise—the result may be true ambiguity, for the first extended period in American history, as to who is president.

That said, the Presidential Succession Act does provide Congress—specifically, the currently Democratic-controlled House of Representatives—with a final point of leverage in such scenarios. While cabinet members generally must meet the same qualifications for office as others in the line of succession, they also must fulfill one more requirement that does not apply to the speaker or president pro tempore: They must “not [be] under impeachment by the House of Representatives at the time the powers and duties of the office of President devolve upon them.” Moreover, as impeachments carry over across congresses—as made clear by the fact that officials have been removed by the Senate on the basis of impeachment by the House of the prior Congress—such action could arguably be pursued by either the House of the current 116th Congress or the incoming 117th Congress, so long as it is done before the presidential and vice presidential vacancies arise on Jan. 20.

In theory, this provides a mechanism by which the House could effectively modify the line of succession to land on members of Trump’s cabinet who they believe will be more amenable to compromise. Of course, the House could pursue impeachment only if adequate grounds exist—a legal determination over which members of Congress exercise broad authority, but that is nonetheless rooted in objective law and historical practice. That said, members of the House and others have already accused several members of Trump’s cabinet, including Pompeo and Barr, of conduct that might warrant impeachment. Normally, an impeachment of a Trump cabinet official might seem quixotic given that the Republican-controlled Senate is unlikely to remove cabinet members from office. But if the House becomes concerned by the role these officials may come to play under the Presidential Succession Act, then it may find reason to pursue impeachment proceedings in order to block their eligibility for the presidency. Alternatively, to avoid the public embarrassment and political risks that impeachment might entail, these officials might be persuaded into resigning prior to Jan. 20 as part of some compromise, removing them from the line of succession and allowing the acting presidency to pass to another member of Trump’s cabinet.

The end result would be a compromise candidate of sorts: a member of Trump’s cabinet, but one selected through a process of elimination from his or her peers by the Democratic-held House. This person would be no one’s first choice—or, for that matter, anyone’s choice at all. But the official would serve as acting president until Congress can finally count the electoral votes, the House or Senate could complete their contingent elections, or consensus is reached—through the Supreme Court or elsewhere—that a qualified speaker of the House or president pro tempore can stand in the line of presidential succession.

***

The process for selecting the president is, if nothing else, immensely complex. But this complexity has most likely contributed to its stability over time. Vesting different parts of the process in so many state and federal officials makes it difficult for any one faction to corruptly dictate the outcome. And for this reason, meddling in the result would require control of numerous state legislatures, governors and members of Congress—and a willingness on the parts of all of these entities to compromise the legitimacy of the very system that empowers them.

That said, such a scenario isn’t as difficult to imagine today as it may once have been. And the closer the race, the easier it becomes to manipulate the process. When victory is just a manner of a few electoral votes, the universe of actors who need to collaborate to affect the outcome becomes much smaller. And previously inconsequential ambiguities in the system can take on new relevance as they provide political actors with ways to pursue their political interests without openly undermining the system.

Of course, this same logic works in reverse as well, allowing those who may simply lose the race for the presidency to cast it as stolen. This in turn can provide incentives for perhaps the most dangerous scenario: one in which a particular faction facing defeat instead seeks to undermine the system in order to weaken its opponents. There are countless pressure points that the right political actors could use to derail the process altogether if doing so was in their political interests. Ideally, norms of good faith and adherence to liberal democratic principles would prevail over these efforts. But even in the best of times, those principles do not always carry the day.

Various actors can take steps to reduce some of these risks. But for the most part, in 2020, the die has already been cast. At this point, the best way to avoid many of the worst scenarios is simply for one candidate or another to win by a large enough margin that the costs of chicanery outweigh the likely benefits. If the margins are instead close, then the incentive for manipulation grows greater. In that case, the United States may well find itself walking down some of these difficult paths in the weeks and months to come.

.jpg?sfvrsn=3f72484e_5)