Just How Outrageous Was the Lewandowski Hearing?

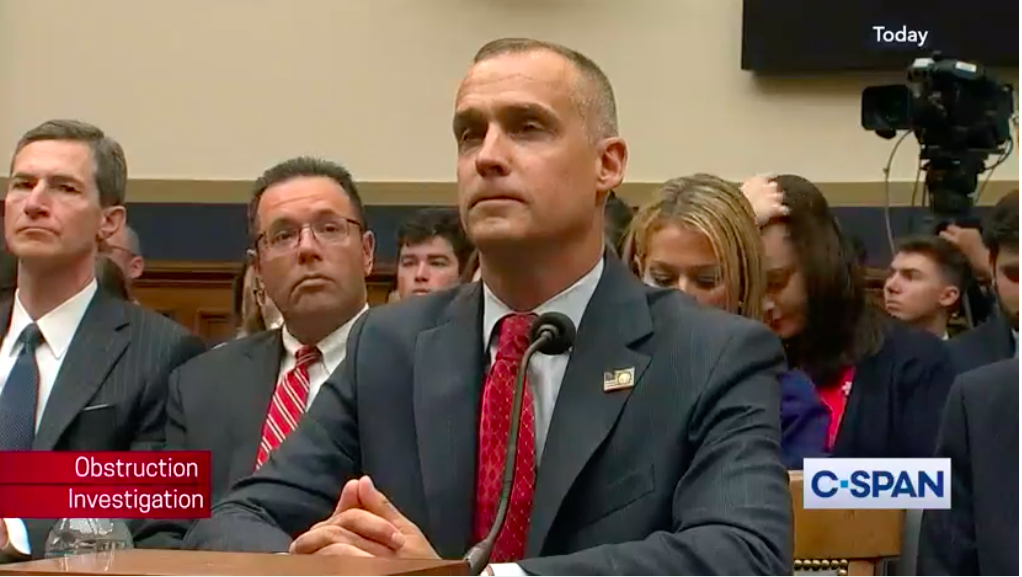

On Sept. 17, former Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski testified before the House Judiciary Committee in an impeachment investigation hearing titled “Presidential Obstruction of Justice and Abuse of Power.” He had been subpoenaed by the committee to testify, along with Rick Dearborn (former White House deputy chief of staff) and Rob Porter (former White House staff secretary).

On Sept. 17, former Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski testified before the House Judiciary Committee in an impeachment investigation hearing titled “Presidential Obstruction of Justice and Abuse of Power.” He had been subpoenaed by the committee to testify, along with Rick Dearborn (former White House deputy chief of staff) and Rob Porter (former White House staff secretary). All three play key roles in parts of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report, submitted to Congress last April, on Russian interference in the 2016 election and the president’s efforts to impede that investigation.

Dearborn and Porter did not show up for the hearing. The day before, Chairman Jerrold Nadler received a letter from the current White House counsel, Pat Cippollone, including copies of memos from the Department of Justice to the president advising that the president could “lawfully direct” Dearborn and Porter not to appear based on a legal theory of “testimonial immunity.”

At the five-and-a-half-hour hearing, Lewandowski was at times combative. He forcefully defended President Trump and admitted without remorse that he lies to the media. He also confirmed several key facts in the Mueller report related to the president’s efforts to impede the investigation—under focused questioning from the committee’s Democrats and committee counsel. At the same time, however, he refused to answer questions about the substance of any conversations he had with the president or senior presidential advisers beyond the information expressly contained in the report. Whenever asked to do so, he repeated the same line: “Congressman, the White House has directed I not disclose the substance of any discussion with the president or his advisors to protect executive branch confidentiality. And I recognize that this is not my privilege, but I am respecting the White House’s decision.” A separate letter to Nadler from Cipollone confirmed Lewandowski was so directed and offered as support various legal rationales based on the doctrine of executive privilege. Lewandowski also declined to answer some questions about his communications with Trump during the presidential transition—periodically consulting with White House lawyers sitting directly behind him in the hearing.

Was Lewandowski’s conduct unprecedented? The executive branch has, for decades, been developing and applying to itself legal theories, rooted in the separation of powers, to limit information and testimony provided to Congress. But in applying these doctrines to Lewandowski, Dearborn and Porter, the administration has stretched these theories in unprecedented ways that could significantly erode Congress’s constitutional powers—including the power to investigate, as well as Article I, Section 2, Clause 5, which states that “The House of Representatives ... shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.”

What can the House of Representatives do in response to protect its own constitutional equities? The options are either not immediately satisfying or controversial. The House is already pursuing several civil contempt actions—most notably against former White House counsel Don McGahn—but such cases could take years to resolve. Another option is exercising Congress’s so-called inherent contempt power to detain a contemnor. A third option—fining the contemnor for noncompliance as part of an exercise of the inherent contempt power—is starting to get more serious consideration in the House but is unprecedented and untested.

Porter and Dearborn: “Testimonial Immunity”

Letters provided by the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) to the White House the day before the hearing assert that both Dearborn and Porter are “absolutely immune” from any compelled congressional testimony in their capacities as former advisers to the president, meaning that the two do not even have to show up at a hearing. The letters state that these claims of “testimonial immunity” are “rooted in the separation of powers and derive[] from the President’s status as the head of a separate, co-equal branch of government.” The substantive argument is that, because the president’s advisers serve as his alter ego, compelling them to testify would undercut the independence and autonomy of the presidency. Lawfare contributor Jonathan Shaub has written extensively, here, here and here, on how prior administrations have framed and applied the theory of testimonial immunity.

Between World War II and 2008, as described here, close presidential advisers (including former counsels and special assistants) appeared before congressional committees to offer testimony on “more than seventy occasions.” The executive branch’s theory of testimonial immunity, also called absolute immunity, dates to a 1971 memo written by William Rehnquist, then the head of OLC. President George W. Bush asserted absolute immunity to prevent his former counsel Harriet Miers from testifying before Congress in 2007. That case went to court, and the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia considered—and rejected—the theory of absolute immunity. The Miers case settled before the appellate court issued an opinion on the merits of the immunity doctrine, however, and the lack of appellate law on the subject has allowed OLC—under both the Obama and Trump administrations—to reject the reasoning of the district court’s opinion and continue to assert absolute immunity for senior presidential advisers.

Unlike prior administrations, however, the Trump White House has applied the theory of testimonial immunity repeatedly and much more broadly, claiming it protects a wide swath of former White House staffers from talking to Congress, rather than a select few who are extremely close to the president. And it is unclear whether there are any meaningful boundaries that would limit its application even further. The administration relied on it to direct Hope Hicks, the former White House communications director, not to answer the committee’s questions in a closed-door interview and to direct senior adviser Kellyanne Conway not to appear at a congressional hearing about an official conclusion that she had violated the Hatch Act numerous times in her public appearances. The White House was set to try to block former White House counsel Don McGahn’s former chief of staff, Annie Donaldson, from answering the committee’s written questions until Donaldson struck a deal with Nadler that allowed her to submit written responses instead of giving public testimony.

The letters asserting absolute immunity for Porter and Dearborn cite as precedent an OLC memo dated May 20 justifying a claim of testimonial immunity for McGahn. That claim is currently being tested in court: On Aug. 7, the House Judiciary Committee filed a lawsuit asking a federal court in Washington, D.C., to force McGahn to comply with the committee’s subpoena for his testimony. (The timeline for a decision in the case is unclear.)

Notably, in its filings in that case, the committee raised the stakes by stating that the Judiciary Committee is in the process of determining whether to recommend articles of impeachment against the president based on the obstructive conduct described by the special counsel, and that it “cannot fulfill this most solemn constitutional responsibility without hearing testimony from a crucial witness to these events.” Likewise, the Sept. 17 hearing in which Lewandowski appeared was conducted under the auspices of a resolution passed by the committee on Sept. 12 outlining certain procedures that apply to “the presentation of information in connection with the Committee’s investigation to determine whether to recommend articles of impeachment with respect to President Donald J. Trump.”

This is another way that the application of testimonial immunity to Dearborn and Porter is unprecedented: It is being made in the context of impeachment proceedings and in the face of the committee’s exercise of the House’s power to impeach pursuant to Article I, Section 2, Clause 5, of the Constitution.

The outcome of the McGahn case could thus have far-reaching consequences for the executive branch theory of testimonial immunity, and for Dearborn and Porter. The White House counsel is considered one of the closest advisers to the president. If a court finds McGahn does not enjoy testimonial immunity, it is virtually assured that neither Dearborn, nor Porter, nor Hicks would either. Even if the court held in favor of McGahn, however, the opinion’s reasoning would almost certainly be premised on his position as one of the president’s closest advisers. Its application to Porter, Dearborn, Hicks and others would likely remain quite tenuous, and that issue would probably still require litigation.

Lewandowski: Presidential Communications Privilege and “Prophylactic Executive Privilege”

The claims of privilege the White House asserted with respect to Corey Lewandoski’s testimony took several forms. The first type—an assertion of presidential communications privilege—represents the core of executive privilege that was first recognized in U.S. v. Nixon. As John Bies’s primer on the subject notes, protecting the confidentiality of communications between presidents and their senior advisers serves to protect candor in presidential deliberations. The relevant letter from Cippollone to Nadler asserts that:

Mr. Lewandowski’s conversations with the President and with senior advisers to the President are protected from disclosure by long-settled principles protecting executive branch confidentiality interests and, as a result, the White House has directed Mr. Lewandowski not to provide information about such communications beyond the information provided in the portions of the Report that have already been disclosed to the Committee.

Is anything unprecedented here?

First, the idea that the White House can “direct” Lewandowski—who was never an official in the Trump administration—is unprecedented. Prior efforts to direct individuals in this way have been addressed only to current or former government officials. As Shaub and others have pointed out, the White House does not have effective control of former officials because such individuals are not formally subject to the direction of the president or other superior executive branch officials. The same is true, of course, of those who have never been government officials—like Lewandowski. (This is why, traditionally, subpoenas to third parties who are not subject to executive branch control are a particularly effective oversight tool for gaining access to otherwise confidential information.)

But Lewandowski was plainly eager to follow the president’s direction. Going forward, then, the question arises of what effect, if any, the precedent-setting nature of such direction by the president will have on a private citizen who wants to testify about communications the president asserts are protected by executive privilege.

Then there is a question of whether the president can validly assert executive privilege over communications between the president and an individual who is neither a current nor a former official. The Cipollone letter confidently claims that “[t]he confidentiality interests protecting Presidential communications are not limited solely to communications between the President and his advisers within the Executive Branch. Rather, a President must frequently consult with individuals outside of the Executive Branch, and it is well settled that those communications are also subject to protection.” It cites an earlier Department of Justice memo, from 2007, in which Paul Clement, then the solicitor general and acting attorney general, concluded “that communications between White House officials and individuals outside the Executive Branch, including with individuals in the Legislative Branch, concerning the possible dismissal and replacement of U.S. Attorneys, and possible responses to congressional and media inquiries about the dismissals, fall within the scope of executive privilege.” No court ever addressed this assertion, however.

The 2007 memo also went a step further in its analysis. It noted that the committees offered no compelling explanation or analysis as to why access to confidential communications between White House officials and individuals outside the executive branch are “demonstrably critical to the responsible fulfillment” of the committee’s functions and that, “absent such a showing, the Committees may not override an executive privilege claim.” Notably, this additional analysis does not appear in the Cipollone letter.

The doctrine of executive privilege, as described generally by the courts in several executive privilege cases, is not strictly limited to internal executive branch communications. It is not clear, for example, that Congress could automatically gain access to all of a president’s emails that go to an outside party. (Of course, records that relate to, or have an effect on, the president’s carrying out of constitutional, statutory, or other official or ceremonial duties are supposed to be captured by the Presidential Records Act—so there is a question of why Lewandowski’s notes were not.) Bootstrapping from there, the question is whether the president can validly assert executive privilege over communications between the president’s close advisers and someone who is neither a current nor a former official. Again, no court has addressed this issue, though the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit has found that executive privilege applies to communications with senior White House advisers solicited by and received from others in the executive branch.

But based on the substance of Lewandowski’s testimony, there is a more fundamental question of how these doctrines can be validly asserted here. Lewandowski does not appear to have been advising the president on anything. Rather, he was summoned by the president to ferry a message to the attorney general demanding that Jeff Sessions take control of the Mueller probe. It’s not clear how the purpose of executive privilege over presidential communications—which is to allow the president to receive candid advice—is applicable here.

Finally, the Cipollone letter asserts a kind of “prophylactic executive privilege” over discussions Lewandowski had with Trump during the presidential transition that “may relate to decisions the President-elect would be making once he assumed office,” which “may implicate deliberative process privilege and other Executive Branch confidentiality interests.” The letter goes on to state that in order to preserve the president’s “ability to assert executive privilege over the information discussed above, and to protect the prerogatives of the Office of President, a member of my office will attend the hearing on September 17 and will advise, as necessary, with regard to specific questions that implicate privileged matters.”

No court has ruled on this kind of assertion or privilege and, as Shaub has pointed out, this nonspecific type of assertion represents a new and extreme conception of the president’s constitutional authority that threatens to render congressional authority immaterial.

Next Steps?

The Lewandowski hearing is a reflection of two things: (1) legal uncertainty about the scope of executive privilege, and (2) an administration willing to push all ambiguities in nearly all circumstances because it perceives no political costs associated with its actions and recognizes that Congress has no simple, uncontroversial and effective recourse. Importantly, the costs of delay here are borne entirely by Congress, not the administration; if Congress spends months litigating and ultimately wins, the administration is no worse off than if it had simply complied with the subpoena in the first instance.

On the first point, evaluating the legitimacy of the application of executive branch doctrines to these facts is difficult because there is little relevant case law from the Article III branch of government. Notably, in addition to the McGahn case, the House of Representatives has gone to the courts in a number of other cases, including to obtain copies of tax and accounting records from Mazars, Deutsche Bank and Capital One, and the Treasury Department and IRS. But all of those cases are pending, and it is unclear what the timeline for resolution will be on any of them. So for now, case law offers no concrete limiting effect on the administration’s assertions.

On the second point, in the past, the principal force guarding against unfettered use of these executive branch theories has been political fear of overreach. That fear is thought to be heightened in the context of impeachment proceedings. But there is not much evidence of such fear in this administration. So the White House will almost certainly feel free to continue to push the bounds of these doctrines as far as it can.

What else can the House do?

Without support from Senate Republicans, it will be difficult for House Democrats to muster the broader congressional tools that might have some impact. As I wrote in January, in theory, Congress could look to its other constitutional tools—like delaying confirmation hearings, refusing to move forward on legislation the president needs to achieve his agenda, using the power of the purse to withhold support for administration programs, initiating impeachment proceedings and perhaps even utilizing arcane arrest powers—to vindicate its prerogatives. But even if Democrats had such cooperation from Senate Republicans, it is not clear which tools would actually work on this president.

What programs does the president care so strongly about that he wouldn’t rather see them cut than give up information he doesn’t want to surrender? He is already utilizing emergency powers to pay for his highest priority—a southern border wall. As to legislation, it is not clear that there are any major policy initiatives from the White House that would require legislative action. Confirmations? On Jan. 6, the president actually said he is in “no hurry” to get his Cabinet members confirmed; “I sort of like ‘acting’ [because] it gives me more flexibility; do you understand that? I like ‘acting.’” And as to budgetary pressures—like, say, cutting off funds for presidential travel to his own resorts—that would require the coordinated action of both houses of Congress.

It remains to be seen whether Congress will utilize untested tools, like its inherent contempt power, to impose fines or detain those who defy congressional subpoenas. Congress’s inherent contempt power is derived from the legislative branch’s own constitutional authority to detain and jail a contemnor until the individual complies with congressional demands. There is precedent for detailing individuals pursuant to the inherent contempt power, but it has not been done since 1935 when a former Herbert Hoover administration official was held briefly in the Willard Hotel. (While there is no “Capitol Jail,” the Capitol Police do maintain a holding cell a few blocks away at the Capitol Police Department.) It is hard to see the administration not intervening to contest such an action.

Both Nadler and Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff have expressed interest in imposing fines on contemnors—rather than jailing them—pursuant to the inherent contempt power. As Kia Rahnama wrote in Lawfare in June, the law in this area remains underdeveloped but it might well be possible. Depending on how it is done, levying such a fine for contempt would likely require the House to adopt new rules for the imposition of fines and to adopt sufficient procedures to satisfy constitutional due process.

****

It remains to be seen which tools will work in the current political environment, and whether the erosion of Congress’s role as a check on the presidency can be checked by the courts. The ultimate recourse would be to impeach the president for impeding Congress’s valid assertion of its constitutional roles of investigation and impeachment. But that won’t happen if Congress is unable or unwilling, on a bipartisan basis, to position itself as the proper repository for the American public’s trust on these matters.