Minnesota FACE Off: A Deep Dive Into the St. Paul Church Protest Case

Unpacking the Don Lemon indictment, its factual allegations, the elements the government must prove to convict, and the potential defenses available to the accused.

-(1).jpg?sfvrsn=ccaf7c0_5)

Two strikingly different narratives have emerged from the Jan. 18 protest at Cities Church in St. Paul, Minnesota.

In one telling, a group of peaceful protesters briefly interrupted a Sunday worship service to call attention to an issue they considered worthy of public scrutiny: a pastor at the church who reportedly serves as a top official in a local U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement field office. Among those who entered the church were two journalists—the former CNN anchor Don Lemon and independent reporter Georgia Fort—who say they were there to cover the protest in an exercise of their First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and of the press.

The other narrative—advanced by the Justice Department and senior administration officials—tells the story of a “takeover-style attack” by a mob of “agitators” who disrupted a religious service and left churchgoers fearing for their lives. In this version, the protest was not an exercise of peaceful assembly but a concerted conspiracy to deprive congregants of their First Amendment rights to worship freely. Lemon and Fort, for their part, are cast in this telling not as journalists but as co-conspirators who took part in the disruption under the guise of reporting.

These dueling narratives—and the competing constitutional rights they supposedly implicate—will soon be tested in federal court. Last month, the government unsealed an indictment charging nine people, including Lemon and Fort, with intentionally interfering in religious worship and conspiring to deprive worshippers of their civil rights. The case is being overseen by Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Harmeet Dhillon, who recently suggested that more charges could be on the horizon. “I believe every single person who participated in this should be arrested,” Dhillon told journalist Catherine Herridge during a Feb. 5 interview.

The indictment follows a series of unusual procedural moves and aggressive rhetoric by Justice Department officials, who have made little secret of their desire to vilify the defendants and use the case to make an example of them. That broader backdrop tells a story of its own—a story about the state of justice at the Justice Department—one we tell in a separate piece entitled "When Life Gives You Lemons’: A Minnesota Case Study in How the Trump Administration Warps Justice” and published today.

Here, we focus on the indictment itself: the factual allegations, the elements the government must prove to secure a conviction, and the potential defenses available to the accused. A close analysis of the charging document reveals that the case is far from the slam dunk some officials have portrayed it to be. Not only are the charges vulnerable to pre-trial dismissal on several grounds, but the prosecution’s narrative sits in noticeable tension with facts currently reflected in the public record.

On that score, the charges appear to reflect a strained effort to force a square peg into a round hole. The Cities Church protest may fairly be characterized as disruptive, disrespectful, or even unlawful under local or state trespass law. But the federal charges look like overreach at best—and something far more troubling at worst.

The Allegations

On Jan. 29, a federal grand jury in Minnesota issued an indictment against Lemon and eight others in connection with the Cities Church incident. Among Lemon’s co-defendants are Georgia Fort, an independent journalist who has maintained that she was not participating in but reporting on the protest; Nekima Levy Armstrong, an activist and civil rights attorney; and Chauntyll Allen, a member of the St. Paul school board.

The 14-page indictment characterizes the incident as a “coordinated takeover-style attack” on Cities Church, repeatedly referring to the defendants as “agitators.” According to the charging document, the defendants and other unnamed individuals gathered in the parking lot of a shopping center near the church on the morning of Jan. 18. There, group leaders—identified as Levy Armstrong and Allen—allegedly provided instruction on how to carry out the “operation,” which prosecutors say was dubbed “Operation Pullup.”

The indictment alleges that Lemon livestreamed portions of the planning meeting, telling his audience that he was in Minnesota “with an organization that was gearing up for a ‘resistance’ operation against the Federal Government’s immigration policies.” He also allegedly “took steps to maintain operational secrecy” by reminding others “to not disclose the target of the operation” to the livestream audience.

Following the meeting, the defendants allegedly traveled by car to Cities Church, where they “entered the church to conduct a takeover-style attack.” The indictment alleges that the defendants disrupted the worship service by yelling, blowing whistles, and making what it describes as “aggressive and hostile” gestures while chanting slogans, including “ICE Out!”, “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!”, and “Stand Up, Fight Back!” According to the indictment, congregants perceived these actions as “threats of violence” and a “potential prelude to a mass shooting.”

Prosecutors further allege that the defendants “physically obstructed” churchgoers as they attempted to exit or move about within the sanctuary. According to the indictment, this conduct included “physically occupying the main aisle and rows of chairs near the front of the church.”

Lemon and Fort, specifically, are accused of standing in “close proximity” to the pastor while Lemon peppered him with questions intended to “promote the operation’s message.” At another point, the document alleges, the former CNN anchor positioned himself at the church’s main entrance, where he sought to confront congregants with “facts” about U.S. immigration policy, thereby obstructing them as they attempted to exit. Fort, for her part, is accused of standing in front of a minivan in the church parking lot while she interviewed Levy Armstrong, the supposed leader of the conspiracy.

According to the indictment, these and other actions forced the worship service to end early and caused most congregants to flee the building out of fear for their safety. Prosecutors also allege that the defendants’ conduct “resulted in bodily injury to one congregant,” though the charging document does not specify the nature of the injury or how it occurred.

The Charges

All nine defendants are charged with felony offenses under two statutes: 18 U.S.C. § 248(a)(2) and 18 U.S.C. § 241.

18 U.S.C. § 248(a)(2)—The FACE Act

The Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act may appear at first glance to be an unusual fit for a charge in this case. Best known as a 1994 law enacted in response to a series of violent and obstructive protests at facilities providing abortion services, the statute establishes federal criminal penalties, as well as a civil cause of action, against anyone who uses force, threats of force, or physical obstruction to interfere with a person seeking or providing reproductive health services.

Less well known, however, is that the act’s protections extend beyond reproductive health care facilities. Under 18 U.S.C. § 248(a)(2), it is also a federal crime to use “force,” “threat of force,” or “physical obstruction” to intentionally “injure, intimidate, or interfere with any person lawfully exercising or seeking to exercise the First Amendment right of religious freedom at a place of religious worship.”

This provision is the by-product of a failed attempt to derail the bill entirely. According to former GOP Senate Judiciary Committee staffer Ed Whelan, it was initially proposed as an amendment by Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), who opposed the bill, in an effort to complicate its passage. But to the surprise of Hatch and his staffers, Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) agreed to incorporate the amendment, citing attacks on Black churches. The result is that the FACE Act applies to sites of religious worship, though it has rarely been used in that context.

For those sorts of attacks, prosecutors have historically relied on a different civil rights law: the Church Arson Prevention Act, which was enacted in 1988 and is codified at 18 U.S.C. § 247. Section 247 prohibits, among other things, “intentionally obstruct[ing], by force or threat of force, ... any person in the enjoyment of that person’s free exercise of religious beliefs.”

In a 2016 letter to Sens. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) and Mike Lee (R-Utah), then-Assistant Attorney General for Legislative Affairs Peter Kadzik pointed out that the department had “prosecuted dozens of cases of violence directed at houses of worship and interference with the free exercise of religion under 18 U.S.C. § 247, a statute that is broader in scope than the FACE Act.” It was precisely because of “the availability of § 247,” he wrote, that the department “has not filed any criminal or civil actions under the FACE Act in this enforcement area.”

Section 247 has been employed in cases ranging from Dylann Roof’s massacre at Emanuel AME Church in South Carolina to an Arizona man’s attempt to intimidate worshippers by strapping a backpack to a toilet. In fact, just last year prosecutors used the statute to charge and convict a Virginia man who attempted to carry out a mass shooting at a church with hundreds of worshippers present. (One of the authors of this piece was part of that prosecution team.)

Against that backdrop, the Cities Church prosecution reflects something of a departure from the Justice Department’s historical preference for charging Section 247 in cases implicating attacks on houses of worship. In fact, to our knowledge, the Cities Church prosecution reflects the first time that the government has pursued criminal charges under the FACE Act’s religious worship provisions. It follows what appears to be the first-ever civil action filed by the department under the FACE Act’s religious worship provisions. Last fall, the department sought injunctive relief and damages against protesters who allegedly targeted a New Jersey synagogue. At the time, Assistant Attorney General Dhillon said it was the first use of the FACE Act to protect access to places of worship.

The government’s newfound enthusiasm to deploy the FACE Act in house-of-worship cases may stem from the statute’s broader scope when compared to Section 247. The former can apply even to nonviolent physical obstruction, while the latter requires proof of force or threats of force. That broader application may make the FACE Act more appealing in cases like Cities Church, which does not appear to involve violence, property damage, or “true threats.” This, of course, ignores some of the constitutional issues the religious worship provision presents that are detailed more fully below.

Beyond any legal rationale, the Trump administration’s use of the FACE Act’s house-of-worship provisions may reflect its political priorities. The case comes at a time when FACE Act enforcement has been scaled back significantly in abortion-related cases. During the first week of the second Trump administration, Acting Associate Attorney General Chad Mizelle issued a memorandum in which he decried “abortion-related” FACE Act prosecutions as a “prototypical example” of “weaponization” of the department under President Biden. Citing a need to ensure that federal resources are devoted only to the “most serious violations of federal law,” he announced that abortion-related FACE Act prosecutions will be permitted only in cases involving death, serious bodily harm, or serious property damage—none of which is clearly present in the Cities Church case. One day earlier, President Trump had pardoned 24 defendants who had been convicted of interfering with access to abortion facilities, declaring that they “should not have been prosecuted” at all. Against this backdrop, the administration may view the Cities Church case as a way to respond to that perceived “weaponization” with a high-profile FACE Act case of its own.

What, then, is the prosecution’s theory of culpability in the Cities Church case? The indictment appears to advance two theories.

First, the government alleges that the defendants used “physical obstruction” to intentionally “interfere” with church attendees. Although those statutory terms appear capacious at first glance, Congress defined them narrowly. The act defines “physical obstruction” as “rendering impassable ingress to or egress from a place of religious worship or rendering passage to or from such a place of religious worship unreasonably difficult or hazardous.” To “interfere with” means to “restrict a person’s freedom of movement.” Consistent with those definitions, the indictment alleges that the defendants engaged in conduct designed to obstruct congregants’ freedom of movement, including occupying the main aisle and front rows of the sanctuary, positioning themselves at entrances, and physically impeding congregants as they attempted to leave the service.

Second, the prosecution contends that the defendants used “threats of force” to “injure, intimidate, or interfere with” the church service. The statute defines “intimidate” as “to place a person in reasonable apprehension of bodily harm.” To that end, the indictment emphasizes the defendants’ alleged use of loud, aggressive tactics inside the sanctuary—yelling, chanting slogans, blowing whistles, and making what it characterizes as “hostile” gestures. Prosecutors further allege that several congregants interpreted this conduct as threatening and feared imminent violence, with some believing the disruption could be a prelude to a mass shooting. Taken together, the indictment suggests, these actions amounted to “threats of force” sufficient to place congregants in reasonable apprehension of bodily harm and thereby to “intimidate” or “interfere with” the exercise of their religious freedom within the meaning of the act.

Finally, the indictment also alleges, without specifying further, that the defendants’ conduct caused “bodily injury” to a congregant. That allegation carries significant sentencing penalties. Under the FACE Act, violators who cause such bodily injury may be imprisoned for up to 10 years. Absent bodily injury, the statutory maximum is 18 months’ imprisonment; if the violation involves “exclusively a nonviolent physical obstruction”—that is, not involving force or threat of force—the maximum is six months.

18 U.S.C. § 241—Conspiracy Against Rights

While the FACE Act targets a relatively circumscribed range of conduct, the other offense charged in the indictment—18 U.S.C. § 241—sweeps far more broadly. The statute traces its origins to the Enforcement Act of 1870, which was enacted in response to post-Civil War organized violence aimed at suppressing Black civil rights and political participation. Specifically, Section 241 prohibits conspiracies “to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate” any person in the free exercise or enjoyment of rights secured by the Constitution or federal law.

In order to secure a conviction at trial, the government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant (a) conspired with another to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate one or more persons; (b) voluntarily and intentionally joined in that conspiracy; and (c) at the time of doing so, intended to interfere with the free exercise or enjoyment of a right or privilege secured by the Constitution or federal law.

Charging Section 241 alongside a substantive FACE Act violation offers multiple advantages to the prosecution. The most obvious is sentencing exposure: A violation of Section 241 carries a maximum sentence of 10 years’ imprisonment, with enhanced penalties available if certain aggravating factors are met.

Section 241 also offers doctrinal advantages. The statute requires proof only that the defendants conspired to violate a right or privilege—not that they actually violated it. What’s more, courts have interpreted key statutory terms in Section 241 more expansively than comparable language in the FACE Act. In the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit—which includes the District of Minnesota—jurors are instructed that “injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate” are not technical terms but encompass “any conduct intended to prevent the free action of other persons.” The FACE Act, by contrast, defines “intimidate” more narrowly, requiring proof that a defendant placed another person in “reasonable apprehension of bodily harm.”

Though Section 241 casts a wide net, the Supreme Court has imposed limits to address vagueness concerns. Specifically, Section 241 requires proof of specific intent. Accordingly, liability under Section 241 attaches only where the government can prove that the defendant’s purpose or intent in joining the conspiracy was to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate a person in the free exercise of a right secured by federal law.

To that end, how one defines the relevant right at issue is central to determining criminal culpability under Section 241. The Supreme Court underscored this point in United States v. Kozminski, in which it affirmed the reversal of two Section 241 convictions because the district court had defined the scope of the underlying right too expansively in its jury instructions. In doing so, the Court stated that a predicate right or privilege for purposes of Section 241 must be “made specific” by the “express” terms of the federal law that secures that right or privilege, or “by decisions interpreting them.”

Historically, Section 241 has been applied to alleged conspiracies to interfere with a broad range of rights. Its most high-profile modern application was against none other than one Donald J. Trump. His four-count indictment for trying to subvert the 2020 presidential election alleged that he violated the statute by participating (with unindicted co-conspirators) in a “conspiracy against the right to vote and to have one’s vote counted.” That right—the right to vote—has served as a predicate in a long line of Section 241 cases.

In the Cities Church case, the underlying right is less orthodox. The indictment alleges that the right or privilege at issue is the “exercise of the First Amendment right of religious freedom at a place of religious worship, as secured by Title 18, United States Code, Section 248(c).” The number two official in the Civil Rights Division, Jesus Osete, posted that the charge reflects the “first time in U.S. history” that the Justice Department has used Section 241 “alongside the FACE Act’s provision protecting houses of worship.” (As noted above, we believe this is the first-ever criminal prosecution under the FACE Act; it is not clear whether Osete was making the further claim, which is likely accurate, that this is the first Section 241 prosecution involving a predicate right secured by Section 248.)

While unconventional, the use of Section 241 in this case may reflect both prosecutorial strategy and Assistant Attorney General Dhillon’s personal interest in the statute. Even before the indictment was filed, Dhillon publicly highlighted Section 241’s potential as a sentencing enhancement in the Cities Church case, observing on The Benny Show that the Biden Justice Department had used Section 241 alongside the FACE Act to secure longer sentences in abortion-related cases. She has also been personally involved in Section 241 litigation: Last year, she argued a Section 241 appeal before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit in a Biden-era FACE Act prosecution of abortion-rights activists—an unusually direct role in litigation for a division head at the Justice Department. All of which may suggest that the decision to charge Section 241 in the Cities Church case may reflect Dhillon’s enforcement priorities as the head of the Civil Rights Division.

The Legal Battles Ahead

The indictment raises a number of issues we’ll likely see litigated through pretrial motions and, if it gets there, the parties’ cases at trial.

The First Amendment

In a statement following Lemon’s arrest last month, his attorney, Abbe Lowell, invoked his client’s First Amendment rights. “Don has been a journalist for 30 years, and his constitutionally protected work in Minneapolis was no different than what he has always done,” Lowell said. “The First Amendment exists to protect journalists whose role it is to shine light on the truth and hold those in power accountable.”

The government, unsurprisingly, took the opposite view. “[C]laiming ‘I’m a journalist’ doesn’t give you a pass to break the law,” Dhillon wrote in a Feb. 3 post on X.

So how does the First Amendment factor in here? Are the journalist defendants shielded by any special First Amendment protections? And for that matter, are the protesters shielded by the First Amendment too? There are several possible arguments, though any direct First Amendment challenge to the indictment itself is unlikely to succeed.

Let’s start with the journalist defendants. At a basic level, both are likely to argue that they were present solely to report on the protest and did not engage in any illegal conduct. In other words, they will assert factual innocence. Their claimed role as journalists engaged in newsgathering activities may therefore play a central role at trial, potentially raising reasonable doubt as to whether they joined a conspiracy or intentionally interfered with congregants’ freedom of movement. That defense, however, does not rely on the First Amendment. It is a factual argument, not a constitutional one.

But what if one assumes that the government’s allegations against the journalists are true? Could Lemon and Fort argue that they are shielded from prosecution under the First Amendment because they were there in a newsgathering capacity?

Such an argument is unlikely to prevail. As the Supreme Court has noted, there is a “well-established line of decisions holding that generally applicable laws do not offend the First Amendment simply because their enforcement against the press has incidental effects on its ability to gather and report the news.” The Court has held that a newspaper may be held liable for breach of contract for publishing the name of a source who was promised anonymity; a journalist enjoys no constitutional shield from having to disclose sources in criminal investigations; and the press is not constitutionally protected from the execution of search warrants that conform to the Fourth Amendment. In other words: The First Amendment does not provide journalists with a special exemption from generally applicable laws.

None of which is to say that the charges against Lemon and Fort do not raise serious concerns about press freedom. Their arrests come at a time when many in the media are concerned about the chilling effect of the Justice Department’s increasingly aggressive posture toward journalists. Early on in her tenure, Attorney General Pam Bondi rescinded a policy that precluded the Justice Department from seeking records or compelling testimony of journalists in leak investigations absent limited circumstances. Then, in January, the FBI conducted an early-morning search at the home of Washington Post reporter Hannah Natanson, whose work devices were seized in relation to a leak investigation. Against this backdrop, the arrests of Lemon and Fort reflect yet another escalation.

Federal prosecutors typically do not criminally charge journalists for their conduct covering a protest that resulted in the arrest of participants. Still, the rarity with which journalists are charged for criminal violations committed in the course of newsgathering has historically reflected prosecutorial restraint, not a special constitutional protection. That restraint has long served as an informal but important buttress for press freedom. Its erosion raises serious concerns—but it does not alter the First Amendment’s limited role in shielding journalists from generally applicable criminal laws.

What, then, of the defendants writ large? Are there First Amendment arguments available even to those who are not journalists?

Any of the defendants—journalist or not—could seek dismissal of the indictment on grounds that the FACE Act or Section 241 are facially unconstitutional restrictions on speech under the First Amendment. That argument would almost certainly fail. Courts have repeatedly considered such challenges with respect to both statutes, finding that neither the FACE Act nor Section 241 violate the First Amendment on their face.

Similarly, all of the defendants could, in theory, argue that the FACE Act or Section 241 is unconstitutional as applied to the facts of this case because it infringes their rights of free speech and peaceful assembly. That argument is also unlikely to succeed. The First Amendment protects expressive activity, but it does not protect conduct that intrudes on the rights of others by employing force, threats of force, or physical obstruction. (Whether the government can prove such conduct occurred is a separate question, discussed below.) Even more importantly, the First Amendment generally does not protect expressive activity on private property.

Still, the fact that direct First Amendment challenges are unlikely to carry the day does not mean that First Amendment concerns drop out of the case altogether. To the contrary, they are likely to surface indirectly in a range of pretrial motions—whether framed as claims of selective or vindictive prosecution or challenges to the sufficiency of the indictment. At trial, meanwhile, the defendants’ expressive activity may bear on whether the government can meet its burden of proof on key elements of the charges. In other words: The First Amendment may not ultimately invalidate the indictment, but the values it implicates will likely loom large in shaping the legal battles ahead.

Selective or Vindictive Prosecution

One possible pretrial motion with a First Amendment flavor would argue for dismissal of the indictment on grounds that the defendants are being unconstitutionally subjected to selective prosecution. The equal protection component of the Due Process Clause “prohibits the government from selectively deciding whether to prosecute” based on an “unjustifiable standard.” While normally defendants allege this defense to claim the government has targeted them for membership in a protected class, like race or religion, they can also raise a “class of one” defense by showing that they have been “intentionally treated differently from others similarly situated and that there is no rational basis for the difference in treatment.”

The structure of the “class” and “similarly situated” group may look different depending on which defendants raise this defense. Lemon and Fort, as journalists, may bolster their argument, for example, by identifying examples of prior FACE Act prosecutions where journalists tagged along with violators yet confronted no charges. The other defendants, meanwhile, could highlight others who have protested at locations subject to FACE Act protections and not been prosecuted. Generally, the more similar the comparator group is to the defendant’s circumstances, the stronger the defense is. This may present a hurdle for the defendants if they cannot identify similar activity specifically at a house of worship that was not charged.

The defendants could also go one step further and argue that their charges are the result of an improper vindictive prosecution. Generally, and specifically in the Eighth Circuit, where this case was charged, a prosecution “designed solely to punish a defendant for exercising a valid legal right” violates due process. This presents a heavy burden on the defense, which must show that the government brought the prosecution as a result of a “vindictive or improper motive.”

The protester defendants could allege the government has vindictively targeted them if they have a history of lawful protests against ICE operations in Minnesota. However, absent evidence such as statements by the Justice Department, the White House, or Trump reflecting an animus against these protestors divorced from any legitimate prosecutorial considerations, it will be a difficult defense to raise successfully.

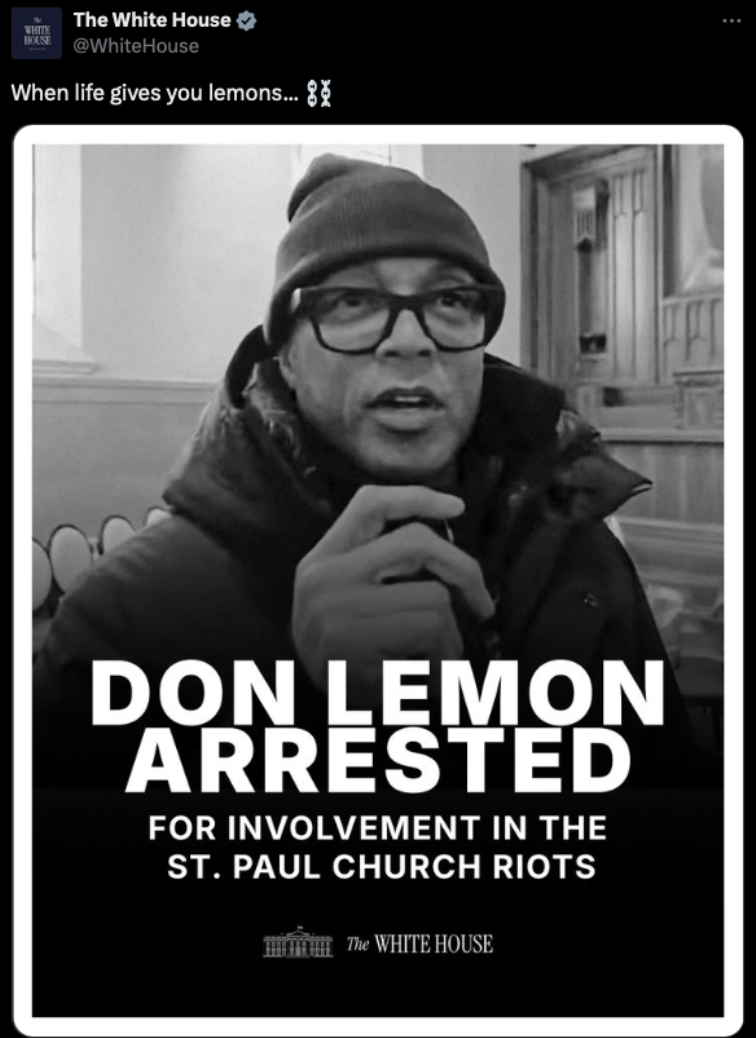

For that reason, though, Lemon’s argument may be stronger. He could argue he has over the years exercised his First Amendment right to speak out about Trump, which has ultimately led to these charges. And he could strengthen his claim by pointing to Trump’s longtime animus against him, Trump’s reaction to his arrest (calling Lemon a “sleazebag,” “a washup,” and noting that the arrest is “the best thing that could have happened to [Lemon]”), the weakness of the evidence against him (as detailed below), and the White House’s response on X to the arrest:

These motions are typically an uphill battle. Courts are often hesitant to impede upon the “broad discretion to enforce the Nation’s criminal laws” held by “the Attorney General and the United States Attorneys.” That is because “the presumption of regularity” normally supports their prosecutorial decisions and, in the absence of clear evidence to the contrary, courts “presume that they have properly discharged their official duties.” The Trump administration’s abnormal efforts to investigate and/or prosecute defendants like Kilmar Abrego Garcia and some of the president’s perceived enemies, however, have called that presumption of regularity into question. Lowell, Lemon’s criminal defense attorney, has recently made these same arguments against the government in a separate troubling prosecution against New York’s attorney general, Letitia James.

Failure to State an Offense—Right “Secured” by Law

There may also be a more pointed—and very different—First Amendment-related problem at the heart of the indictment: the government’s potentially overbroad definition of the right “secured” by U.S. law that the defendants allegedly conspired to infringe under Section 241. If so, that count may fail to state an offense, warranting dismissal under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 12(b)(3)(B)(v).

The problem arises from the indictment’s framing of the predicate right. The government alleges that the defendants violated Section 241 by conspiring to deprive congregants of a right “secured” by federal law. According to the indictment, that “right” is defined as a “First Amendment right of religious freedom at a place of religious worship,” which the government claims is “secured” by a provision of the FACE Act, specifically 18 U.S.C. § 248(c).

That framing appears vulnerable to attack on several grounds.

Most fundamentally, the government seems to articulate the “right” at issue as a generalized First Amendment right of religious freedom. The problem is that the First Amendment protects the free exercise of religion only against governmental interference, not private conduct. And courts have long held that purely private interference with rights protected solely against government action cannot support a prosecution under Section 241 unless the defendants acted “under color of law”—that is, under actual or apparent governmental authority. Here, the indictment alleges no state action whatsoever. Insofar as the predicate right rests on the First Amendment of the Constitution, Section 241 is inapplicable.

Perhaps in anticipation of this problem, the government attempts to ground its asserted “First Amendment right of religious freedom” not in the text of the Constitution itself, but in statute. Specifically, the indictment cites Section 248(c) of the FACE Act as the source of the relevant “First Amendment” right of religious freedom. But the statutory text does not support that expansive characterization.

As a textual matter, Section 248(c) does not “secure” the right described by the government. Rather, Section 248(c) is a civil standing provision. It authorizes civil actions by any person “aggrieved” by conduct prohibited elsewhere in the statute, provided that the person was “lawfully exercising or seeking to exercise the First Amendment right of religious freedom at a place of religious worship.” This language does not define a substantive right, nor does it convert the First Amendment into a statutory entitlement enforceable against private actors. Instead, it establishes a threshold requirement for who may sue under the act.

The reference to the First Amendment in Section 248(c) serves as a limiting function: It ensures that the protections of the act apply only to lawful religious exercise. For example, if a purported religious service involved unlawful conduct that is not protected by the First Amendment—such as human sacrifice—participants would lack standing under the FACE Act.

The provision that actually defines the substantive right protected by the FACE Act is found in Section 248(a)(2), which the indictment conspicuously omits. That subsection prohibits the use of “force, threat of force, or physical obstruction” that is intended to “injure, intimidate or interfere with any person lawfully exercising or seeking to exercise the First Amendment right of religious freedom at a place of religious worship.” As in Section 248(c), the reference to the First Amendment in Section 248(a)(2) merely limits the statute’s reach to conduct that interferes with lawful religious expression. It does not secure a generalized First Amendment right against private interference with religious worship.

The only right actually “secured” by the FACE Act is a narrow, conduct-specific one: the right to be free from force, threats of force, or physical obstruction intended to interfere, intimidate, or injure a person in the exercise of religion at a place of worship. That right is materially narrower than the expansive formulation advanced in the indictment.

This overbreadth is underscored by the government’s earlier characterization of the predicate right. When the case was initiated by criminal complaint, the government identified the relevant right as the “free exercise of religion at a place of religious worship secured by the FACE Act.” The complaint and supporting affidavit cited Section 248(a)(2), not Section 248(c), and made no reference to a First Amendment right to religious expression at a place of worship.

This shift in framing appears designed to broaden the asserted right beyond what the FACE Act actually secures. In doing so, however, the prosecution places the Section 241 charge on unstable footing. As the Supreme Court has explained, Section 241 requires proof of specific intent and prohibits only “intentional interference with rights made specific either by the express terms of the Federal Constitution or laws or by decisions interpreting them.” Because the indictment now rests on an expansive First Amendment right against private interference with religious expression—rather than the narrowly defined, conduct-specific right established by Section 248(a)(2)—it arguably fails to identify a right actually “secured” by law. Without a clearly established legal right as its predicate, the indictment cannot sufficiently state an offense under Section 241 and is subject to dismissal.

That said, the Section 241 charge may survive pretrial dismissal if a court construes the indictment’s reference to Section 248(c) as implicitly incorporating the conduct-specific prohibitions set out in Section 248(a)(2). Indeed, at least one district court has upheld a Section 241 charge based on a conspiracy to violate Section 248(c)’s provisions relating to reproductive health services.

Nevertheless, the indictment’s current articulation of the predicate right exposes it to significant legal vulnerability. Even if the Section 241 count is not dismissed outright, the government’s expansive framing of the right will almost certainly be contested through other pretrial motions. Those challenges could include motions in limine to restrict the scope of the government’s argument at trial, as well as briefing regarding the proper jury instructions defining the predicate right necessary to sustain a Section 241 conviction.

Failure to State an Offense—Criminal Conspiracy

The Cities Church defendants may also advance additional, discrete arguments in support of a motion to dismiss for failure to state an offense.

One arguable vulnerability lies in the indictment’s allegations concerning certain elements of the Section 241 charge. To withstand a motion to dismiss, the government must allege facts that, if true, constitute the essential elements of a Section 241 conspiracy as to each defendant.

Specifically, the indictment must allege facts showing the existence of a criminal agreement—namely, an agreement to “injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate” congregants in the free exercise of their “First Amendment right to religious freedom at a place of religious worship,” as secured by 18 U.S.C. § 248(c). It must further allege that each defendant knowingly and voluntarily joined that agreement and did so with the specific intent to deprive individuals of the right identified in the indictment.

At least one defendant has already suggested that the indictment fails to allege facts sufficient to establish the elements of a Section 241 conspiracy. On Feb. 6, Ian Austin—an Army veteran charged alongside Lemon and the others in connection with the Cities Church protest—filed a motion to dismiss for failure to state an offense. Among other arguments, Austin contends that the indictment does not adequately allege facts showing that interference with religious exercise was the object of the conspiracy. Instead, he argues, the indictment characterizes opposition to federal immigration enforcement—and to a federal official involved in that enforcement—as the objective of the “operation.” This misstep, Austin argues, is dispositive at the pleading stage.

Austin’s motion faces an uphill battle under the deferential standard governing Rule 12(b)(3)(B)(v) motions to dismiss and the relatively low bar indictments must meet to sufficiently put defendants on notice of the charges against them under Rule 7. Nevertheless, it highlights potential difficulties the government may confront in proving its Section 241 charge at trial, where it must establish both the existence of the agreement and each defendant’s knowing and intentional participation beyond a reasonable doubt. Indeed, those difficulties could arise even earlier in the proceedings. For example, if the government moves to admit co-conspirator statements under Federal Rule of Evidence 801(d)(2)(e), it must first demonstrate the existence of the agreement by a preponderance of the evidence.

Conspiracy law is admittedly broad. Under Eighth Circuit precedent, an agreement need not be formal, written, or even verbalized. Nor is membership in a conspiracy governed by a rigid evidentiary formula. There is no minimum role a defendant must play, and participation can be inferred based on the defendant’s conduct alone.

That breadth, however, is not without limits. Mere presence at the scene, parallel conduct, or association with others does not, standing alone, establish that a defendant joined a conspiracy. Nor does mere knowledge of the conspiracy’s existence—or even approval of its objectives—suffice to show joinder. Section 241’s requirement of specific intent further narrows the statute’s reach.

At trial, the government may face specific challenges in proving these elements against certain defendants such as Austin or Lemon. With respect to Lemon, for example, the evidence suggests he arrived shortly before the incident and had minimal prior communications with alleged co-conspirators, largely limited to learning the protest’s location and refraining from disclosing it. Critically, however, the law makes clear that “it is not enough” that alleged participants “simply met, discussed matters of common interest, acted in similar ways, or perhaps helped one another.” To be guilty of conspiracy, Lemon must have known of the existence and the purpose of the charged agreement and joined it. Absent such knowledge and joinder, he cannot be convicted—even if his conduct incidentally furthered the alleged conspiracy.

The Commerce Clause

For all the debate over free speech in the Cities Church case, the constitutional provision most likely to derail this indictment isn’t the First Amendment—it’s the Commerce Clause. Specifically, the defense may raise a challenge to the indictment on grounds that the FACE Act’s house-of-worship provisions are unconstitutional because Congress lacked authority to enact them under the Commerce Clause.

This argument begins with the foundational constitutional principle that Congress may legislate only within the scope of its powers enumerated in the Constitution. When Congress enacted the FACE Act in 1994, it expressly invoked two such authorities: The Commerce Clause and the 14th Amendment’s Enforcement Clause. The Commerce Clause is generally considered to be the much stronger basis for the FACE Act’s constitutionality, given that the Supreme Court has held that legislation enacted under the 14th Amendment’s Enforcement Clause must be directed at state actors rather than private citizens, a principle articulated most recently in United States v. Morrison. But whether the Commerce Clause provides a basis for the religious worship prong remains largely untested.

As the Supreme Court has explained, the Commerce Clause permits Congress to regulate “the channels of interstate commerce,” the “instrumentalities of interstate commerce, and persons or things in interstate commerce,” and “activities that substantially affect interstate commerce.” This power extends even to “purely local” activities so long as they are “part of an economic class of activities that have a substantial effect on interstate commerce.”

To ensure that legislation enacted under the Commerce Clause remains within these limits, Congress often includes a “jurisdictional hook”—a statutory requirement that the regulated conduct have some nexus with interstate commerce. The statute more commonly deployed to prosecute attacks on religious institutions, 18 U.S.C. § 247, is a paradigmatic example: It explicitly requires the government to prove that the offense “is in or affects interstate commerce.” The FACE Act, by contrast, lacks this language entirely. As former Civil Rights Division prosecutor Laura-Kate Bernstein observed recently, the absence of a “clear, court-tested constitutional hook” may be one reason why career prosecutors have historically relied on Section 247 to address attacks on religious freedom instead of the FACE Act.

The Eighth Circuit has concluded that Section 248(a)(1)—the prong of the statute regulating access to reproductive health services—is a “valid exercise of Congress’s power to regulate activity that substantially affects interstate commerce.” In reaching that conclusion, the court relied in part on congressional findings “showing that the blockading of clinics and the use of violence and threats of violence against clinics’ patients and staff depressed interstate commerce in reproductive health services.” The court reasoned that the provision and receipt of reproductive health services constitute a “commercial activity” and that Congress had a rational basis for concluding that the conduct prohibited by FACE substantially affects interstate commerce. Other courts of appeals have reached the same conclusion.

That reasoning, however, does not neatly translate to the FACE Act’s religious worship provision under Section 248(a)(2). Although there are few cases involving that prong, at least one appellate decision arising from a civil action under the act has addressed its constitutional vulnerability. Concurring in the judgment, Judge John Walker of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit would have held the FACE Act’s religion prong to exceed Congress’s powers under the Commerce Clause. “In prohibiting violence against worshippers at places of religious worship,” he wrote, the FACE Act “regulates local, non-economic conduct that has at best a tenuous connection to interstate commerce.” The statute contains “no congressional pronouncement that would tie the proscribed conduct to activity affecting interstate commerce,” nor “does the legislative history contain any findings that connects acts of worship or violence against worshippers at places of religious worship to interstate commerce.” Walker found it “telling that Congress made specific interstate commerce findings as to abortion clinics but not to places of religious worship.”

Absent a valid exercise of Congress’s Commerce Clause authority, the FACE Act’s religious worship provisions are unconstitutional and unenforceable. That conclusion is fatal not only to any prosecution under the FACE Act’s religious worship provision but also to the government’s Section 241 charge, which depends on the deprivation of a right “secured” by that provision. In other words: If the courts that hear the Cities Church case agree with Judge Walker’s analysis, dismissal of the indictment is required.

Proof Problems

More broadly, for both counts, the central question is whether the government can prove that the defendants engaged in the conduct alleged in the indictment, assuming the government’s case survives motions to dismiss.

We do not know what the government presented to the grand jury or the full scope of evidence collected during the investigation. What we do have is the government’s account in the indictment and Lemon’s livestream video. A key issue at trial will be whether the video aligns with the allegations. A preliminary review suggests significant discrepancies may undermine key elements of the government’s case at a purely factual level.

Consider, for example, the conduct described in “Overt Act #15”:

While inside the Church, defendants ARMSTRONG, ALLEN, KELLY, LEMON, RICHARDSON, LUNDY, CREWS, FORT, and AUSTIN oppressed, threatened, and intimidated the Church’s congregants and pastors by physically occupying most of the main aisle and rows of chairs near the front of the Church, engaging in menacing and threatening behavior, (for some) chanting and yelling loudly at the pastor and congregants, and/or physically obstructing them as they attempted to exit and/or move about within the Church.

As seen in the video from minute 42 through minute 51, the government alleges the defendants “oppressed, threatened, and intimidated” congregants. These terms are derived from the text of Section 241 and Section 248, and only “intimidate” is statutorily defined as to “place a person in reasonable apprehension of bodily harm to him- or herself or to another.” Some of the specific means by which the defendants allegedly did so—“engaging in menacing and threatening behavior, (for some) chanting and yelling loudly at the pastor and congregants”—may come down to whether a jury believes the protesters’ actions amounted to “threatening” or “menacing” behavior sufficient to place a person in reasonable apprehension of bodily harm. For this, the government will likely introduce victim-congregant testimony that was featured in the complaint affidavit.

A look at the video, however, raises questions about whether a jury would buy this claim. One specific manner the government alleges the protesters used to oppress, threaten, and intimidate congregants, however, is physical obstruction. Again, Section 248 defines “physical obstruction” as “rendering impassable ingress to or egress from a ... place of religious worship, or rendering passage to or from such a ... place of religious worship unreasonably difficult or hazardous.”

But consider timestamp 45:24 of the video, screenshotted below:

The video appears to depict most of the protesters standing near the sanctuary and in nearby front rows. Lemon says multiple times that he is not joining the group but instead capturing the events as a journalist and indeed moves around separately from the group talking to various individuals. Before and after this point in time, the video depicts a number of individuals, likely congregants, leaving the church through the front exit (circled on the right in the screenshot above), and two side exits (one circled on the left of the screenshot above, and one behind the cameraman visible at later points in the video). In fact, as the government’s original complaint affidavit repeatedly noted, the video shows “multiple parishioners exiting Cities Church through multiple doors”—a fact the government did not include in the indictment.

The defendants may line these facts up to each part of the legal definition of “physical obstruction” to show how they fall short. They may first argue the government cannot show the defendants’ actions were in the statute’s prohibited areas—“ingress to,” “egress from,” or “passage to or from” the church—because their conduct was inside the church and in a localized area. To interpret these terms as covering any and every path inside the church, the argument would go, would stretch these terms too broadly. In any event, they may argue that the government cannot meet its burden of proving the defendants rendered any paths “impassable” or “unreasonably difficult or hazardous,” considering the video evidence of people entering and exiting throughout the protest.

Short of proving the defendants successfully physically obstructed or interfered with the congregants’ free exercise of religion, the government may turn to “attempt” and “aiding and abetting” theories of liability included in the indictment. Section 248 also prohibits one from attempting to injure, intimidate, or interfere with the congregants by force, threat of force, or physical obstruction. Likewise, the government charged the defendants with 18 U.S.C. § 2, alleging they aided and abetted each other and others in committing a violation of Section 248. If the government succeeds under either argument, the defendants could be found guilty and face the same sentencing exposure as if they were convicted of committing the Section 248 violation themselves.

Under either theory, however, the government cannot escape the burden of proving a specific mindset. To prove that the defendants attempted to commit a violation of Section 248, the government will still need to prove each possessed the same specific intent to commit the crime and not to do something else in the church (for example, simply protest or cover protests journalistically). And not only does aiding and abetting law have the same specific intent requirement, but it also requires the government to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that someone committed the crime for the defendants to aid and abet. Absent more, the video evidence alone does not appear to satisfy these elements.

Similarly, consider the conduct detailed in “Overt Act #23”:

With other co-conspirators standing nearby, defendants LEMON, RICHARDSON, and FORT approached the pastor and largely surrounded him (to his front and both sides), stood in close proximity to the pastor in an attempt to oppress and intimidate him, and physically obstructed his freedom of movement while LEMON peppered him with questions to promote the operation’s message.

At 51:00 through 52:45, the video depicts Lemon freely moving toward the sanctuary and stating, “let’s see if we can talk to the pastor.” Eventually, Lemon positions himself near the pastor. From left to right, the video depicts Lemon, someone who identifies himself as the pastor of the church, a hand holding a blue microphone with the letters “GF” in front of the pastor (presumably Fort), and different individuals moving next to the pastor and walking away.

Throughout their brief interaction, Lemon asks the pastor questions, shifting his microphone between himself and the pastor, and the pastor answers those questions. Without more, this video does not appear to be evidence that Lemon and Fort approached the pastor “in an attempt to oppress and intimidate him.” Nor is it clear that Lemon, Fort, or any others “physically obstructed” the pastor’s “freedom of movement.” In fact, the pastor appears to view Lemon as separate from the protesters: After earlier describing “these protesters” who disrupted his service, the pastor, at 52:32, tells Lemon to “also leave this building,” and Lemon asks whether the pastor wants “us to chronicle what happened.” Eight seconds later, the pastor turns to his left and freely walks away. Lemon says, “thank you very much,” walks in the opposite direction of the pastor, and proceeds to interview a different congregant.

Finally, consider the government’s allegation in Overt Act #28:

At one point, defendant LEMON posted himself at the main door of the Church, where he confronted some congregants and physically obstructed them as they tried to exit the Church building to challenge them with “facts” about U.S. immigration policy.

Put bluntly, at no point does it appear Lemon “physically obstructed” anyone as they tried to exit the church. At 59:00, Lemon says, “Let’s go out front and see what’s happening” and proceeds to exit the church through an open side door and make his way to the front doors. By 59:45, Lemon makes it to the closed front door and states, “This is where folks are leaving.” He then opens the door, stands to the side, and holds the door open for people who appear to be congregants exiting the church. Lemon states, “The pastor is hugging members of the church as they are about to leave.” At 1:00:05, Lemon, still holding the door open and standing to the side, asks an exiting congregant, “What do you think of this?” The congregant holds his hands up as he exits the church and begins talking to Lemon, as depicted below.

Both Lemon and the congregant take steps away from the church down what appears to be a ramp. When the congregant says, “I’m sorry that you guys are so angry,” Lemon responds, “I’m just chronicling, I’m not with the group.” The congregant refers to a second person with him as his son, who walks past Lemon and away from the church. The congregant stays and answers Lemon’s questions while standing outside the church. At 1:00:57, Lemon says again, “I’m a journalist, they’re activists.” During the interview, multiple individuals exit the church and walk behind Lemon—who is turned and looking at the congregant, not the church doorways, as shown below:

By 1:02:06, Lemon has stopped interviewing the congregant, who has walked away from the church with his son. Lemon reenters the church through the front doors and remarks that the “crowd has significantly dwindled.” At 1:02:25, Lemon is standing inside the front of the church on the side of an interior doorway and asks another congregant: “Can I talk to you, sir? What do you think of this?” The congregant proceeds to stand in the doorway while Lemon remains on the side, and the congregant answers Lemon’s questions. At 1:04:00, Lemon and the congregant continue to speak, while Levy Armstrong appears to lead a line of protesters past Lemon and the congregant and out of the church. As depicted below, multiple individuals similarly walk through the interior door—past Lemon, behind the congregant, and toward the church exit.

At about 1:05:30, the congregant begins to walk away from Lemon and proceeds toward the church exterior exit. Lemon backs up, opens the church’s entry door with his back, the congregant exits through the doorway past Lemon, and Lemon continues to ask the congregant questions from behind the congregant as he departs the church.

Outside the church, the congregant turns around and speaks to Lemon a second time. By 1:05:53, the congregant turns around and walks away from Lemon and the church again. Lemon turns and faces the camera and begins speaking into his microphone. At 1:06:02, the congregant, now standing further outside the church on the steps, turns back around and begins engaging with Lemon a third time. Eventually, the congregant walks away from Lemon, turns back to the steps to the church, and reenters the church through the front doors—totally unobstructed by anyone, let alone Lemon.

Based on this video, it does not appear Lemon ever approaches or enters the church again.

In each of these instances, the congregants voluntarily stopped and began speaking with Lemon. To be sure, they each ultimately appear agitated with the substance of Lemon’s questions before they voluntarily end the interview. But the government has not, and cannot, charge Lemon with agitating worshippers. Prosecutors allege that he physically obstructed them as they exited the church. Yet each of these congregants moved freely in and out of the church while interacting with Lemon, who stands at the sides of doorways and even opens the doors for them in some instances.

The video evidence simply does not support the government’s allegation.

* * *

For weeks, political appointees at the Justice Department have advanced their account of the Cities Church case in online forums. In their telling, the defendants were a horde of agitators who conspired to “attack” a church. As the case now moves from chatrooms to courtrooms, that narrative is set to collide with fact and law.

While public attention has largely focused on the journalists’ potential defenses, the prosecution faces a host of legal hurdles and evidentiary problems that could sink the case against all defendants. And because the FACE Act’s religious-obstruction prong remains largely untested, any appellate courts reviewing these issues will, at minimum, be navigating uncharted legal terrain—whether in the context of reviewing convictions or, quite possibly, dismissals.

.jpg?sfvrsn=3792d97a_5)