Palestinian Islamic Jihad’s Balancing Act

The organization's narrow focus on armed conflict has limited its options and appeal at times, but it may now be its greatest strength.

Editor’s Note: Palestinian politics are usually boiled down to relations between Mahmoud Abbas and the Palestinian Authority, which dominate the West Bank, and their Islamist rival, Hamas, which controls Gaza. Missing from this picture is an important third actor: Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), an Islamist bedfellow of, and rival to, Hamas in Gaza. Erik Skare, a researcher at Sciences Po and the author of “A History of Palestinian Islamic Jihad” (Cambridge University Press, 2021), explains why PIJ has become stronger in recent years and the balancing act it must perform in the years to come.

Daniel Byman

***

PIJ was established in the Gaza Strip in 1981 in response to growing frustrations in parts of the Palestinian population. The founding fathers of PIJ were dissatisfied with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) because of its secularism and political concessions, which increasingly signaled a willingness to sacrifice the principle of armed struggle in its aspirations for a Palestinian statelet next to Israel. The Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood was unattractive to these Palestinian Islamists because of its quietism and refusal to participate in armed struggle. According to early PIJ supporters, the Palestinian nationalists ignored Islam and the Palestinian Islamists ignored Palestine. The only solution was to organize a new movement that would fuse nationalist armed struggle and religion. The establishment of PIJ never entailed the formation of a new, distinct ideology but, rather, the rearticulation and combination of several strands of Palestinian political thought—and there are direct lines from the Palestinian armed secular-nationalist currents of the late 1960s to the contemporary organization.

PIJ carried out its first armed operation in 1984 and grew notorious for its spectacular attacks and its uncompromising stance against the Israeli occupation: no negotiations, no two-state solution, and no recognition of Israel in the quest for one Palestinian state from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. Although considered sister movements, PIJ’s modus operandi has largely differed from Hamas, partly because it refuses to participate in Palestinian elections under occupation, essentially ignores social welfare, and prioritizes armed struggle. While Hamas evolved through internal debates concerning how to prioritize violence versus social change, PIJ has focused on armed struggle.

This narrow approach has constrained PIJ. While Hamas has survived by shifting its emphasis to social welfare in periods of intense Israeli counterinsurgency, PIJ’s commitment to violent tactics has prevented it from pursuing alternative political channels when challenged. This has also affected PIJ’s funding. While Hamas has benefited from diversified sources of income, PIJ has never branched out. It has instead depended on Iranian aid since relations were established in the late 1980s—allegedly an annual sum of $70 million, as of 2016.

From Weakness to Strength

PIJ’s one-sided approach may now be the movement’s greatest strength. Hamas must balance maintaining the ethos of a resistance movement while fulfilling its responsibilities as a ruling party. Realizing that new Israeli bombings will further deteriorate the disintegrating living conditions in Gaza, which has been under blockade since 2007, Hamas regularly sits on the fence when hostilities increase and stresses instead that it is in the “Palestinian interest” to avoid escalation with Israel. As Tareq Baconi notes in his excellent book, “Hamas Contained,” the popular support for Hamas depends now on the quality of its governance in Gaza rather than its commitment to the Palestinian resistance.

PIJ, by contrast, unencumbered by governance and its inconvenient responsibilities, continues to earn public support for its confrontational position that only armed resistance against Israel can liberate Palestine. While Hamas is blamed for the deteriorating situation, PIJ positions itself as a principled defender of Palestinian rights. The organization has grown from operating with a few hundred members organized in a loose network of cells in the 1980s to an estimated following of 8,000 people (mainly in Gaza) in 2021.

Other developments in the Gaza Strip have also benefited PIJ. The infighting between Fatah and Hamas in 2007, for example, was reportedly a new source of members for PIJ, as were clashes with Israel. While 13.5 percent of Gaza’s population preferred PIJ in April 2014, 30.8 percent of the same population supported the movement in September 2014 after Israel’s “Protective Edge” bombing campaign. This places PIJ in a similar position to that of Hamas in the mid-1990s, during which period Hamas’s political violence earned it political support and undermined Fatah as disillusionment with the peace process grew.

A More Confrontational PIJ?

PIJ has undoubtedly been aware of the void left by Hamas once it took control over the Gaza Strip in 2007. While the former PIJ leader Ramadan Shallah was careful not to strain an already-complicated relationship with PIJ’s sister movement, some observers claim that PIJ has taken an increasingly provocative line against Hamas under the leadership of Ziyad al-Nakhalah. PIJ is initiating more armed activities without taking cues from Hamas, regularly interfering with the truces between Hamas and Israel.

What happens in Gaza will largely depend on how Hamas responds to the PIJ’s confrontational approach. Hamas has always considered itself the main representative of Palestinian Islamism, and it has reacted strongly whenever it has felt sidelined by its “little brother.” Hamas has arrested PIJ militants in the past for firing rockets from Gaza, and they asked PIJ to hand over “rogue” members to the Ministry of Interior as recently as 2020. These confrontations have also led to violent clashes—for example, PIJ field commander Ra’id Qasim Jundiyya was killed by Hamas security forces in June 2013. It is no wonder, then, that the leadership of Hamas may—to some extent—have welcomed the Israeli assassination of PIJ commander Abu al-Ata in November 2019 because he had persistently interrupted Hamas’s efforts to maintain its truce with Israel. Palestinian artist Majida Shaheen caught popular sentiment when she drew a political cartoon depicting Ismail Haniyeh nervously trying to tame an angry dog with “al-Quds Brigades” on its collar.

Tensions may rise in Gaza if Hamas continues to refrain from military actions against Israel while PIJ positions itself at the forefront. The question is whether Hamas’s reaction will be directed against PIJ to check its rival or against Israel to restore its credentials.

PIJ’s Balancing Act

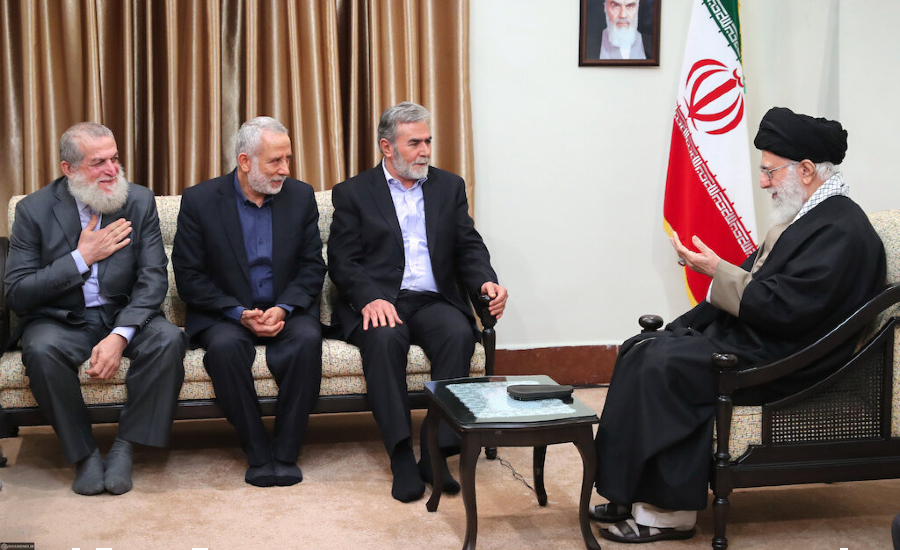

The main issue linked with al-Nakhalah’s tenure pertains to his need to maintain cordial relations with the PIJ’s main patron, Iran, while retaining some political and strategic independence. Iran’s support is required if PIJ wants to continue its growth and sustain its military professionalization, but the credibility of the movement will suffer if it is portrayed as nothing more than a proxy for foreign powers.

While it has been a delicate balancing act in the past, relations between PIJ and Iran have deteriorated since PIJ refused to take sides in the Syrian civil war or to criticize the Saudi air campaign against the Houthis in Yemen. PIJ’s rationale at the time was the perceived necessity of keeping the Palestinian struggle separate from other regional internecine struggles to avoid making Palestine just another regional flashpoint. As senior PIJ figure Khadr Habib stated in 2012, toward the beginning of the war in Syria, “We do not interfere in what is happening in Syria; this is an internal affair.”

PIJ’s leadership is presumably cautious of the ongoing realignment of the political map in the Middle East, which places Hamas and other Muslim Brotherhood affiliates in a camp with Qatar and Turkey and in contention with the “rejectionist axis” that includes Iran, Syria and Hezbollah. But PIJ has never supported the Arab regimes ideologically—PIJ considers them to be subservient stooges to Western colonial interests. As a member of PIJ’s political bureau, Anwar Abu Taha, affirmed when I interviewed him in 2018, “These Arab regimes are authoritarian, they kill their people, they are the agent of the West, and they take their orders from the White House, from London and Paris. … So, we are with those who rose up, with the Arab revolutions, and with the Arab Spring.”

Fed up with its neutrality, Iran struck PIJ activities hard when it decided to cut its funding in 2015 and instead reallocate it to the newly established (but short-lived) al-Sabirin movement in Gaza. Faced with the worst economic crisis in its history, PIJ was suddenly unable to pay the salaries to its militants in the al-Quds Brigades and was forced to lay off workers in its civic and research institutions. Some reports described desperation within PIJ as the organization’s leaders traveled to Algeria and Turkey to find alternative fiscal sources to alleviate the crisis.

Iran renewed its financial aid to PIJ in May 2016, but the restored funding was presumably not a free lunch. One month later, Hezbollah media organization al-Manar declared that PIJ suddenly “stood with the Yemeni people” and that the Saudi intervention against the Houthis was equivalent to targeting the Palestinian cause. If al-Manar’s report was accurate, it seems that one year was the approximate time required before PIJ was forced to publicly renounce its neutrality. The veracity of the report notwithstanding, the incident made clear, as al-Masdar reported, that PIJ “is no longer the spoiled son.” Al-Nakhalah now knows all too well that a light purse is a heavy curse for a movement unfamiliar with self-sufficiency.

Al-Nakhalah could transform the political fabric of the Gaza Strip for the unforeseeable future should he succeed in this balancing act. For now, that means following Iranian dictates with a “yes, but,” provided they are not perceived as too egregious by the PIJ leadership. It is uncertain how skillfully al-Nakhalah can play such a hand. It seems beyond doubt, however, that as Hamas falls farther down the rabbit hole of governance and compromises, PIJ will be able to capitalize on the popular demand for a more assertive representative.