The Quarantine Power: A Primer in Light of the Coronavirus Situation

The U.S. government has begun invoking quarantine authority, so now is probably a good time for a review of the legal architectures that both authorize and constrain the quarantine power.

From time to time, the realm of public health crosses over into precincts that are familiar ground for national security law. This is certainly true for quarantines. Given the anxieties surrounding 2019-nCoV (i.e., the novel coronavirus that emerged in Wuhan, China), and the fact that the U.S. government already has begun invoking quarantine authority as a result, now is probably a good time for a review of the legal architectures that both authorize and constrain the quarantine power.

1. The quarantine dilemma

Before we start in on the substance of the laws, let’s establish a common understanding of what we mean by quarantine and why it can be difficult to decide just when and how to impose one.

Did you know that the word “quarantine” derives from the Italian phrase “quaranta giorni”—that is, “40 days?” That was the rule in 14th-century Venice when a ship arrived and authorities feared it might be carrying the plague: The ship had to wait it out, at anchor, for 40 days. If everyone on board was healthy at the 40-day mark, then and only then could they come ashore.

Of course, quarantines now vary widely in length, but a version of the Venetian phrase has made its way to English and stuck through the centuries. The basic idea remains the same: In case of possible contagion, one must control the movement of potential carriers for a long-enough period to determine whether they are in fact infected.

This approach to risk reduction makes perfect sense. But only if one can put it into practice before the horses are out of the barn, and therein lies a policy (and political) dilemma.

The longer authorities wait to impose a quarantine, and the narrower its scope, the greater the risk that infectious carriers will slip through the quarantine net. For a particularly relevant example, consider this article forthcoming in the CDC’s Emerging Infectious Diseases journal, in which my University of Texas colleague Lauren Ancel Meyers and her co-authors calculated the chances that a person exposed to 2019-nCoV got out of Wuhan prior to China’s imposition of quarantine measures in the city. They determined that it was more likely than not that an exposed person from Wuhan made it to 128 Chinese cities, including five very large ones. Quarantines are hard to implement effectively (especially at scale), even in an authoritarian system in which the government is relatively free to take unpopular actions without facing serious political or legal pushback.

If timing is everything, might it follow that governments should impose draconian quarantines at the first hint of trouble? That might maximize the protective effect, but this isn’t always or even often a realistic option in a free society. The earlier the intervention, the less likely it is that there will be widespread public appreciation of the danger posed by the illness, so it’s more likely that the costs and burdens of a quarantine would spark a backlash. The earlier the intervention, moreover, the more room there is for critics to speculate that the threat may be overstated—perhaps unfairly so (an early quarantine can be the victim of its own success), but perhaps quite fairly so.

This dilemma should look familiar to anyone who has wrestled with whether and when the government should intervene to arrest a person whom it suspects may engage in terrorism in the future but who is not in the midst of or on the verge of such an attack now. In that setting, reducing the risk of false negatives increases the risk of false positives, and vice versa. Quick resort to quarantines at scale sometimes has a similar quality, navigating the harms of action with the potential danger of inaction under conditions of uncertainty. (To be clear, the terrorism-prevention scenario entails a completely different moral judgment, obviously, and (usually) longer lasting and more serious consequences for the persons detained.) Both scenarios also share the potential for nonmerits decision-making by officials who may feel pressure to take highly visible steps demonstrating their attention to and serious engagement with the threat.

All of this suggests we should pay careful attention to who gets to make quarantine decisions, on what grounds the decisions are permitted to be made, and how they can be challenged. So let’s turn now to the legal framework(s), and seek answers to those questions.

2. Are we talking about state law or federal law?

Both.

The ability to legislate to protect public health has always been a staple of state government authority (the classic understanding of the “police powers” belonging to the states is a formulation that expressly references protection of public health, among other things). I’ll say a few words at the end of this post about states and their quarantine powers. But first let’s talk about the federal quarantine power.

3. Explain how federal quarantine law works.

First things first: from where does the federal government get this authority?

On the one hand, the enumeration of the finite legislative powers of Congress found in Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution does not include a clause expressly referencing protection of public health (in the disease context or otherwise). As just noted, safeguarding public health was precisely the sort of thing one would expect to be addressed by the states, both in the founding era and for long thereafter, at least for quarantines applied within the country (what we might call “internal quarantines,” in contrast to “border quarantines,” which pertain to persons seeking to enter the country). On the other hand, Section 8 does give Congress authority to regulate both foreign commerce and interstate commerce. And though there are controversies regarding just how far those commerce authorities can be extended, it is not hard to justify at least some degree of internal quarantine authority for the federal government. When the scope of the interstate commerce authority expanded during World War II, with the Supreme Court’s 1942 Wickard v. Filburn decision, this became clearer.

Two years after Wickard, as it happens, Congress passed the Public Health Service Act, a broad public-health reorganization statute that included a quarantine framework that remains with us today. At the time, federal quarantine authority for persons arriving at the nation’s borders was well established, but internal-quarantine authority for the federal government was a different matter outside the military context. Post-Wickard, however, the grounds for federal legislation for quarantine authority seemed firmer. The Public Health Service Act’s quarantine provisions were indeed understood at the time as war related, yes, but there was more to it than that. Here’s how one contemporaneous observer explained the results:

In addition to the traditional authority to detain infected persons at points of entry into the United States, [the Public Health Service Act] gives a similar power, the existence of which had previously been in doubt, to apprehend, detain, and examine certain infected persons who are peculiarly likely to cause the interstate spread of disease or, in time of war, to infect the military forces or war workers. This power, which is similar to the familiar quarantine authority of State and local health officers, will not at present be exercised with respect to diseases other than the venereal diseases; but it furnishes a potentially important weapon against new infections which may be brought into the United States in the post-war period.

Simply put: Fear that venereal disease would reduce military manpower might have been the proximate cause for the creation of legislation that clarified the federal government’s “internal” quarantine authority, but, even at the time, it was expected that this authority would have broader utility. Contemporary observers saw the value of the quarantine authority in cases of novel disease outbreaks that originate overseas but eventually find their way to the United States in contexts unrelated to war.

Today, this same authority is codified as 42 U.S.C. § 264. Here’s how it works:

The statute opens by granting authority to create regulations “to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases” both from abroad and across state lines. 42 USC § 264(a). Next, the statute confirms that these regulations may include authority to seize and detain persons (to quarantine or isolate them) but only in connection with those diseases that may from time to time be expressly made eligible for this purpose via an executive order. 42 USC § 264(b).

The statute then clarifies that such quarantine authority may be applied to persons in only two situations. The first situation concerns anyone entering the country—i.e., border-quarantine authority. There, broad authority is given: Quarantine can be used on anyone entering an American state or possession from a foreign country or another possession. 42 U.S.C. § 264(c).

The second authority is the internal-quarantine authority, and it is narrower. In that case, the regulations can authorize apprehension and testing of a person only if they are reasonably believed to be in a “qualifying state”—meaning they are infected and are at the communicable or at least pre-communicable stage of that infection. In addition, there must also be a reasonable belief that the person is either moving (or about to move) across a state line, or instead that the person might infect others who are so moving (that last clause likely being pretty easy to satisfy in many if not most instances). 42 USC § 264(d).

4. Which diseases currently qualify for federal quarantine authority?

Since the 1940s, there have been a series of executive orders under the authority of the Public Health Service Act that have added various diseases to the list of those qualified for federal quarantine authority. Over time, the list of qualifying diseases expanded from plague and smallpox, to hemorrhagic fevers (Executive Order 12452), to SARS (Executive Order 13295), to flu with pandemic potential (Executive Order 13375). Then, in 2014, President Obama issued the most recent update, Executive Order 13674, which expanded the SARS-specific language with a broader formulation that captured the possibility of similar but distinct respiratory syndromes that have a potential for pandemic transmission patterns or for high mortality rates.

That 2014 expansion covers 2019-nCoV.

5. Let’s get to the details: What do the regulations implementing federal quarantine authority actually say?

The answer is found in 42 Code of Federal Regulations part 70 (42 C.F.R. 70). Here are the key things to understand:

a. Who decides?

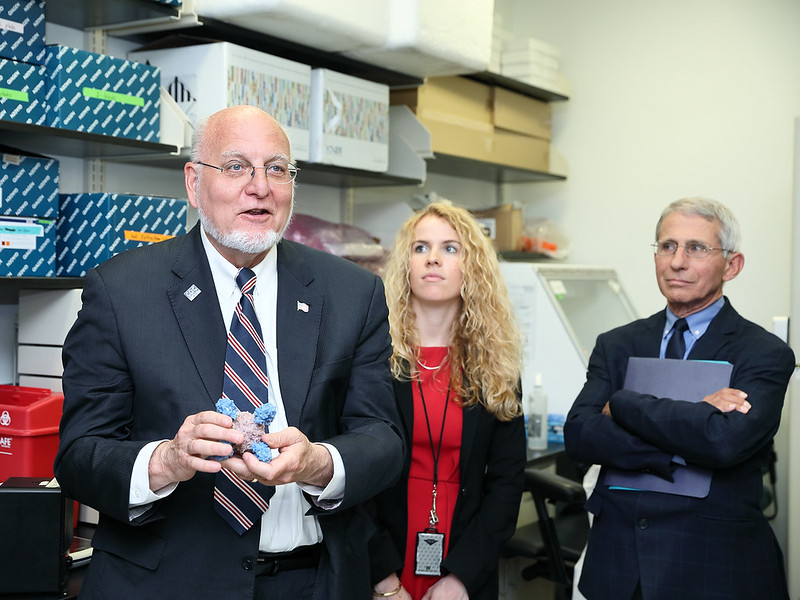

Under 42 C.F.R. section 70.6, the actual authority to issue a quarantine order (or an isolation order, or a conditional release order) is delegated to the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Currently, that’s Robert Redfield. It will be a bad sign if, a few months from now, all of us know that name.

b. What is the standard that determines when the director can issue a federal quarantine order?

The standard in the regulations is simply that of the statute itself, as described above.

c. Does the director have to give an explanation?

Yes. Under 42 C.F.R. section 70.14, the director’s order must not only identify the person or group to be detained but also must give an “explanation of the factual basis underlying the Director’s reasonable belief that the individual is in the qualifying stage of a quarantinable communicable disease.” 42 C.F.R. section 70.14(a)(3). Likewise, the director must explain the basis for believing the person or group to be detained satisfies the statutory requirement about movement across state lines or exposure to others who will so move. See id. at 70.14(a)(4).

d. Is it possible for a detained person to challenge the decision?

First, the regulations themselves require the director to reconsider the situation within 72 hours, regardless of whether the detainee has objected. 42 C.F.R. section 70.15.

Second, the regulations authorize the detainee to request a “medical review” of the director’s decision after the 72 hour reassessment, under 42 C.F.R. 70.16. That review considers two factual questions: Is there really a reasonable basis to believe the person is infected with a covered disease, and is the person in the qualifying stage of that illness (infectious or pre-infectious)?

The medical review is conducted by a designated medical professional (not necessarily a doctor) selected by the director. The detainee may have an attorney, a physician, or other help to present medical evidence and other evidence. If the detainee is indigent, the director can appoint a pro bono representative to assist the person. Additional procedural rights are spelled out in the regulation. Note that the regulations contemplate consolidated reviews where problems of scale may be present.

Ultimately, the medical reviewer does not dictate the outcome but, rather, makes a detailed written recommendation to the director. The detainee can submit a filing to the director that contests the medical professional’s findings and recommendations. The director then decides, for the second time, whether to make a change to the detainee’s status.

e. What about judicial review?

The regulations do not purport to prevent habeas litigation or the like. Indeed, they expressly state that they do not limit access to federal review. But is there any chance of getting somewhere with a federal judge, if the processes just described goes against the detainee?

Not really. Habeas jurisdiction exists, yes, but for a detainee to prevail on the merits would be quite an uphill battle.

In terms of a procedural due process challenge, it bears emphasizing that the government’s interest is at its zenith in this situation, that the consequences of erroneous release of a detainee are significant, that the procedures described above are substantial, and that the maximum length of detention likely is short in relative terms. A Mathews v. Eldridge balancing analysis almost certainly would favor the government in light of all that. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine the litigation running its course before the quarantine order expired.

Should the government make a hash of the required procedures, of course, or use them pretextually, it might be a different matter (particularly if the order of detention is prolonged enough to allow for litigation to develop). So too if there is some indefensibly discriminatory aspect to the scope of a quarantine order (such as a directive that people of a particular racial description be quarantined, but not others who are similarly situated in terms of infection risk).

Another possibility, one that faces all these same difficulties, is the detainee launching an Administrative Procedure Act challenge contesting the CDC director’s finalized determination.

6. What are the penalties for disobedience?

If convicted of violating a quarantine order, a person can be sent to jail for up to a year (see 42 USC § 271(a)).

7. How about state quarantine laws?

Having said all that, it must be emphasized that internal quarantines traditionally are imposed by state governments, not the federal government. Every state has a framework for this. The National Conference of State Legislatures has a handy state-by-state chart of quarantine laws here.

.jpg?sfvrsn=8588c21_5)

-final.png?sfvrsn=b70826ae_3)