U.S. Military Detention and Transfer in Its Fight Against Cartels

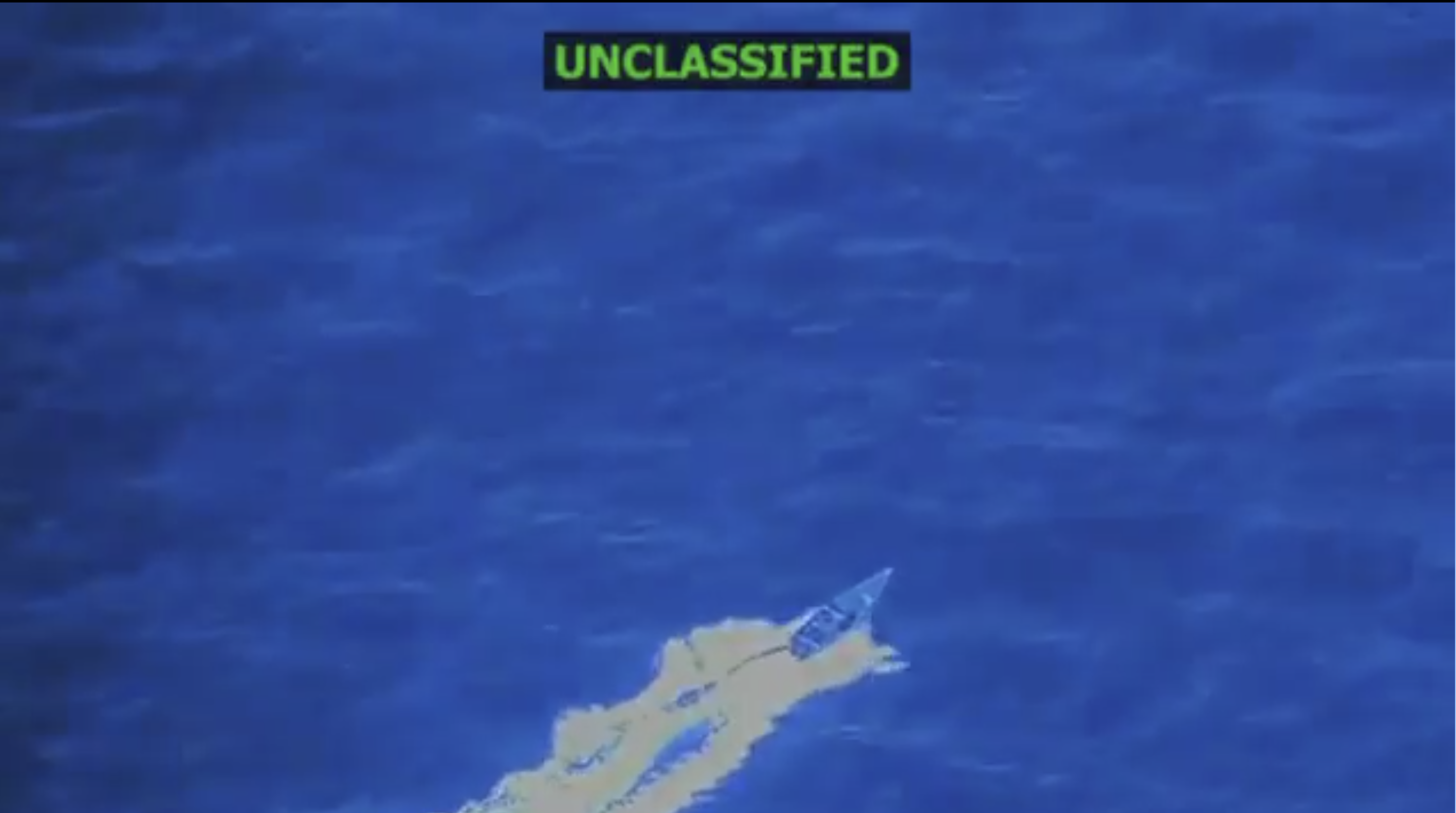

On Sept. 2, a U.S. drone fired at a boat just outside of Venezuelan territorial waters, killing 11 men. In his subsequent War Powers report to Congress, President Trump claimed that the strike was a use of military force in self-defense against drug cartels. While the report did not name a specific group associated with the targeted boat, the president has since associated the attack—and subsequent strikes—with Tren de Aragua (TdA), the same Venezuelan drug cartel for which the Trump administration controversially invoked the Alien Enemies Act to justify deportations of migrants. Trump has deemed the passengers of these alleged drug boats as “narco-terrorists” who are smuggling a “deadly weapon poisoning Americans.” Recent reporting suggests, however, that the boats and their crews may have not been members of TdA at all: “They were fishermen who were looking for a better life,” said one relative of a victim.

Since Sept. 2, the U.S. military has launched at least 12 more attacks, killing more than 60 people. On Oct. 17, news reports indicated that a strike the prior day left two survivors, who the U.S. Navy detained in international waters. By Oct. 18, the administration announced it would repatriate the men to their home countries of Ecuador and Colombia “for detention and prosecution.” Though the detention was resolved quickly with the men being repatriated within days, it marks an escalation in the military’s campaign against drug cartels and raises questions about detention and transfer practices.

(For the sake of the argument, all of the analysis below will assume that the United States is engaged in an armed conflict with cartels, including TdA, per President Trump’s confidential notice to Congress in early October. That conclusion, however, remains hotly contested.)

LOAC Detention: Treatment and Authority

Members of Congress and policy analysts alike have questioned the legality of U.S. military strikes against alleged drug cartel boats under domestic and international law. One month after the first strike, the Trump administration sent a new justification to Congress, claiming the president “determined that the United States is in a non-international armed conflict with these designated terrorist organizations” and calling cartel members “unlawful combatants.” Trump’s declaration squarely frames the strikes under the law of armed conflict (LOAC)—a conclusion some observers have criticized as incorrect in paradigm and factual application. If the U.S. is in an armed conflict with cartels, it is rather uncontroversial that the rules for non-international armed conflicts (NIACs)—that is, conflicts “not of an international character”—would apply, although the president’s earlier invocation of the Alien Enemies Act seems to tie TdA directly to Venezuela’s direction and control. The label “unlawful combatant” draws on the global war on terrorism (GWOT) label attributed to members of al-Qaeda and associated forces, identifying them as belligerents capable of being lawfully targeted in a non-international armed conflict.

Assuming the U.S. is in an armed conflict with cartels, LOAC guarantees minimum standards of treatment for captured fighters. As the Department of Defense’s Law of War Manual acknowledges, “There are no ‘law-free zones’ in which detainees are outside the protection of the law.” In a NIAC, Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions serves as the lodestar for detainee treatment. That article requires that detainees in non-international armed conflict be treated humanely and prohibits torture, cruel treatment, and humiliating and degrading treatment. It also provides for access by humanitarian bodies such as the International Committee of the Red Cross. Additional Protocol II to the Geneva Conventions, which expounds on the law applicable in NIACs, spells out the “fundamental guarantees” of humane treatment for detainees as well as requirements to receive adequate medical care, food, and water.

U.S. domestic law and policy recognize these protections as applying to any NIAC, such as the one the Trump administration asserts it has engaged against cartels. In 2006, the Supreme Court rejected the Bush administration’s argument that Common Article 3 would not apply to the conflict with al-Qaeda, finding that Common Article 3 “bears its literal meaning” and applies to conflicts that are not between nations. Executive Order 13491—issued by President Obama in 2009—recognizes Common Article 3 as the “minimum baseline” of treatment in all armed conflicts, and the Department of Defense acknowledges that Common Article 3 would apply to any NIAC. The Defense Department’s detention policy also recognizes these minimum treatment requirements as well as the fundamental guarantees for detainees in Articles 4-6 of Additional Protocol II, even though the U.S. is not a party.

Executive Order 13491 also requires that the ICRC be given notice and timely access to any detainee. Since the administration has labeled its fight against cartels as a NIAC, these provisions of LOAC provide the baseline treatment requirements for any detainees.

In prior detention cases, the U.S. government has asserted the right under the law of war to detain an enemy combatant until the end of hostilities. Importantly, the government mainly relies on its domestic statutory authority for detention for the duration for hostilities—the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), which the Supreme Court determined authorizes detention as an “important incident[] of war.” No such domestic authorization exists for the government’s use of force against drug cartels. Instead, the U.S. government has relied solely on the president’s powers under Article II of the Constitution. In the early GWOT days, the Bush administration argued that Article II alone permitted the detention of enemy combatants for the duration of hostilities, but the Supreme Court could not reach agreement on this point, instead identifying the detention authority from the statutory authority to use force. This leaves Article II detention authority an open question.

Combatant Status: GWOT Déjà Vu?

Detention in armed conflict presupposes the detainee is in fact a member of an enemy force. But the United States’s experience from the GWOT demonstrates the difficulty of identifying captured individuals as members of an enemy, especially when the battlefield does not involve traditional armed forces. Just as in targeting, the distinction between combatants and civilians is critical to detention: Combatants can be detained until the end of hostilities while civilians must released as soon as the reason necessitating detention no longer exists (for example, in an international armed conflict, civilians could be temporarily detained by an occupying power for imperative reasons of security). After Supreme Court losses in Hamdi and Rasul, the Bush administration established combatant status review tribunals to assess whether detainees were members of al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or associated forces. Analogizing the processing of prisoners of war, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor reasoned that the process could be fulfilled by conducting a review of detainees’ status under the law of war. The tribunals that were eventually established would consider someone an enemy combatant if a preponderance of evidence showed they were part of al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or an associated force—though this system received considerable criticism for the shortcomings in allowing detainees and counsel to confront the evidence against them.

Early in GWOT, the U.S. began placing law of war detainees at Guantanamo Bay, initially under the argument that constitutional protections did not apply to the naval base in Cuba. Once the Supreme Court determined that Guantanamo detainees had full habeas rights, the task of determining whether these individuals—and those captured in armed conflicts—could be detained fell to federal district courts. Whether these people were properly detainable as combatants led to years of litigation challenging both the process itself and factual determinations. Over time, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit developed a functional approach to assessing whether a detainee was “part of” al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or an associated force under the 2001 AUMF. In summarizing parts of this analysis, President Obama’s framework report on the use of force states:

[A] functional analysis may include looking to, among other things, the extent to which that person performs functions for the benefit of the group that are analogous to those traditionally performed by members of a country’s armed forces; whether that person is carrying out or giving orders to others within the group; and whether that person has undertaken certain acts that reliably connote meaningful integration into the group.

Although an extensive corpus of jurisprudence eventually developed around which factors demonstrated membership in a group and the level of evidence required, courts struggled for years to assess what indicated membership in a terrorist organization such as al-Qaeda. Those struggles would increase exponentially with drug cartels, which do not share the structure, membership, training, or force attributes of armed terrorist forces. It would be difficult to identify the function “analogous to those traditionally performed by members of a country’s armed forces” for any men and women picked up on drug smuggling ships.

At a high level, there are already considerable questions about whether TdA and other groups are organized armed groups for the purposes of determining that an armed conflict exists. Those difficulties are compounded by the lack of clarity concerning intelligence used to link the boats off the Venezuelan coast and their passengers to TdA and could prove even more difficult when trying to link an individual’s status to the group. Family members of recently killed men have also acknowledged that the victims of the strikes were in fact transporting drugs, but they dispute connections to TdA. Without that link to cartel membership, these men are not combatants and thus cannot be targeted or detained as such.

Transfers

Within days of capturing the two survivors of the Oct. 16 U.S. military strike outside of Venezuelan waters, the U.S. government repatriated them. The law of war permits detainee transfer from custody before the end of hostilities. Detainees can be transferred to both home countries and third countries, but other restrictions can apply. By statute (8 U.S.C § 1231 Note), the U.S. shall not transfer someone to a country where “there are substantial grounds for believing the person would be in danger of being subjected to torture, regardless of whether the person is physically present in the United States.” Defense Department policy also requires consideration of other forms of ill treatment as well as persecution (refoulement) before a transfer is conducted.

Transfers from U.S. military custody normally require assurances of humane treatment from the receiving country. Those assurances would then be assessed by the Departments of State and Defense against available information, including the country’s human rights record and the likelihood the receiving country would detain and prosecute the individual. These sorts of assurances produced mixed legal reactions for terrorism detainees. The government routinely relied on them, but nongovernmental organizations criticized them as inadequate to prevent harm to returned detainees. The Trump administration’s use of these same assurances for transferring alleged cartel members from the United States has been highly criticized for their ambiguity and evidence suggesting they could not be reasonably relied upon.

Little information has been released about the process by which the Trump administration negotiated the transfer of the two detainees from a U.S. Navy vessel to their home countries—one to Ecuador and one to Colombia. Although the president claims the men were repatriated for prosecution, Ecuadorian officials have stated there is no evidence their national committed a crime while Colombia has said their national will be prosecuted according to domestic law. Since the U.S. transferred both men with the intent that they remain in custody, the required non-refoulement assessment would need to assess their likely treatment in custody.

Future Detention and Judicial Review

The Trump administration has continued to strike vessels in the Caribbean and recently extended its strikes to the Pacific Ocean against unidentified targets. The repeated strikes and U.S. military build up in the Caribbean, coupled with Trump’s public and private criticism of the Maduro regime, all suggest that the U.S. may soon be engaged in conflict with Venezuela. President Trump reportedly confirmed he authorized covert CIA operations in Venezuela and is reportedly considering direct strikes against the country. As long as these strikes continue, the military should anticipate future survivors like the two men recovered in mid-October. The status of these survivors under the law of war and the guarantees they are owed will continue to push the administration’s legal theories on its armed conflict against drug cartels.

The recent repatriation not only quickly delivered the men to their home countries but also clearly had the benefit of limiting legal challenges to their detention. U.S. courts have previously heard claims by law of war detainees in the United States, at Guantanamo, as well as for American citizens abroad. Repatriations remain possible and legal so long as the government complies with the prohibition against refoulement noted above. If detentions continue, four other possibilities should be accounted for.

The first possibility is detention at sea. Indefinite detention of an individual aboard a U.S. Navy vessel would spark practical considerations and potentially legal challenge, although federal court jurisdiction over a noncitizen detained on the high seas would be difficult. For example, in 2011, Navy SEALs captured Ahmed Abdulkadir Warsame on a ship off the coast of Somalia. He remained in the brig of the USS Boxer for two months at sea while being interrogated until the government charged him with federal terrorism crimes in New York.

The second possibility is transfer to third countries. Any third-country transfer of detainees would still need to comply with non-refoulement requirements and assessment of diplomatic assurances, if needed. The Trump administration has already transferred hundreds of other alleged TdA members to the notorious CECOT prison in El Salvador, which has a documented history of torture. And in its past practice of third-country resettlement for Guantanamo, the U.S. government routinely engaged in “delicate diplomatic negotiations” to obtain humane treatment assurances and then independently evaluated the effectiveness of those assurances.

The third possibility is to transfer detainees to Guantanamo. The Trump administration has demonstrated a proclivity for using the U.S. naval base at Guantanamo Bay to process alleged cartel members. Shortly after taking office earlier this year, Trump signed an executive order to “expand the Migrant Operations Center” at Guantanamo to “provide additional detention space for high-priority criminal aliens unlawfully present in the United States.” Since then, the administration has temporarily detained more than 700 migrants at Guantanamo—though at the time of this writing no migrants are being held at the naval base. In 2008, the Supreme Court definitively ruled that the constitutional right of habeas corpus extends to Guantanamo, meaning the detainees would have the right to challenge their detention in U.S. federal court. This could open the door to challenging the evidence connecting detainees to a cartel as well as the Trump administration’s underlying basis for its use of force against an unknown list of cartels.

And the fourth possibility is transfer to the United States. If the United States believes the detainees were intending to smuggle drugs in the United States, as President Trump has asserted, federal prosecutors can build cases to charge them for drug crimes if they can marshal the evidence. For example, after the United States invaded Panama in 1989, it captured Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega as a prisoner of war and transferred him to Florida, where he was convicted on drug charges. Of course, bringing detainees to the United States provides them with constitutional rights to challenge their detention and potential prosecution.

***

The Trump administration seems intent on continuing its military strikes in the Caribbean and Pacific, and it may soon attack Venezuelan territory. Thankfully, the two men captured in October were repatriated quickly rather than lingering in detention. The GWOT era produced painful lessons on the treatment and detention of law of war captives. Only through repeated legal challenges did the U.S. government acknowledge fundamental rights of humane treatment in all NIACs and establish appropriate processes to evaluate individual reasons for detention. And even if legally justified, indefinite detention can become untenable. For example, the U.S. kept some detainees at Guantanamo more than a decade after they were cleared for release, and three men remain in this limbo today. If strikes against alleged cartel boats continue, the detention and treatment of individuals will continue to be one of the many tests of whether the U.S. government has learned the right legal lessons from the war on terror.