Venezuelan Boat Attacks: Utterly Unprecedented and Patently Predictable

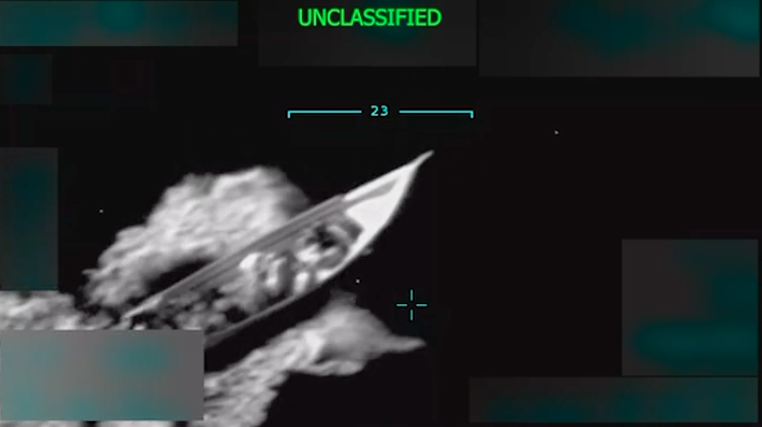

On Sept. 2, a U.S. drone attack killed 11 suspected Venezuelan drug runners on a speedboat in the Caribbean. Legal experts immediately condemned the attack as unlawful. Since then, at least two more such attacks have occurred, and the Trump administration threatens more to come. In a statement to Congress, President Trump sought to justify such attacks on various international legal grounds—including the right to self-defense—on the basis that the boat’s occupants were “terrorists” or, as implied by his reference to “war powers,” that they were targetable as enemies under the law of armed conflict. Reasonable minds trained in international law beg to differ. Every justification put forth by the Trump administration for the attacks is meritless. Even the most conservative of international law scholars, such as John Yoo, who purported to authorize the use of the euphemistically titled “enhanced interrogation techniques” (torture) during the George W. Bush administration, reject the Trump administration’s justifications for these attacks. International law experts have emphasized the extent to which these attacks, and their purported justification, depart from precedent in the U.S. use of force.

My take is a bit different. There is no question that these attacks are unlawful. But many experts overstate the extent to which they were previously unimaginable given past U.S. practice. To be clear, these attacks are meaningfully different from the lethal attacks conducted by prior administrations; in that sense, they are unprecedented. But the legal abuses of the Bush, Obama, and Biden administrations form a foundation upon which the Trump policy is built. A useful analysis—one that provides the context for determining what needs to change to retreat from such unlawful conduct—requires acknowledging that the unlawful policies and practices of the previous post-9/11 administrations make predictable the Trump administration’s current legal overreach. The degree of overreach is an important factor in appreciating the legal risks faced by those who follow illegal orders to conduct these attacks.

Utterly Unprecedented

If the boat’s occupants were running illicit drugs destined for the United States, the proper—and entirely feasible and precedented—response would have been interdiction, arrest, and trial. The Trump administration’s summary execution/targeted killing of suspected drug dealers, by contrast, is utterly without precedent in international law. In fact, there is precedent for considering such attacks, when committed on a widespread or systematic basis, to be a crime against humanity. Former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte is currently facing charges in the International Criminal Court for exactly that reason.

But the fact that these attacks on alleged drug runners are unprecedented is not the only reason to harbor doubts about the administration’s justification for them. The administration’s position is unclear but appears to be that because the boats were manned by members of Tren de Aragua, and because Tren de Aragua has been designated a foreign terrorist organization (FTO), the boats are targetable. But the administration has presented no evidence to support President Trump’s allegation that the individuals on the boat were members of Tren de Aragua, a criminal syndicate. Should such evidence come to light, it would be irrelevant because such a designation does not authorize the use of deadly force under either international or domestic law.

In addition, there’s been little evidence presented to support the premise that Tren de Aragua is, in fact, a terrorist organization meriting an FTO designation, even if it is a criminal one. The term “terrorism” has no single legal definition, but for purposes of designation as an FTO under U.S. law, it is understood as the “premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents.” Think al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and so on. No evidence has been presented to suggest Tren de Aragua’s use of violence is politically motivated. And again, even accepting that Tren de Aragua has been designated an FTO, however dubiously, that does not make its members legitimate targets for the use of military force—even if it does make them subject to sanctions and other legal consequences.

Furthermore, there’s no evidence that these suspected drug runners were engaged in, or about to engage in, an attack against the United States, which is the standard for justifiable resort to force. The notion that this standard could be met by characterizing the importation of drugs as an attack—an argument put forward by Secretary of State Marco Rubio—is a nonstarter. Under the law of jus ad bellum, as reflected in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, the right to use force in self-defense is wisely triggered not by the degree of harm that is prevented but, rather, by the unavailability of methods short of force to neutralize the threat. The fact that Tren de Aragua was designated as a foreign terrorist organization, even if the designation had had a rational basis, does not trigger a power to subject its suspected members to summary execution.

If the administration’s apparent legal rationale fails in all these ways in the jus ad bellum framework, should one interpret its position to be that jus in bello (international humanitarian law, or the law of armed conflict) is the applicable framework? And if so, would that legal framing provide justification for lethal attacks? It is true that the legal strictures discussed above and concerning terrorist designations and the use of force in self-defense do not apply to an ongoing armed conflict. In war, the enemy is targetable not because they pose a threat, but merely because they are the enemy. However, this alternative justification is also unavailing, as there was, and is, no war between the United States and Tren del Aragua. We know this because war (or, in international legal parlance, armed conflict) has specific, universally recognized elements as articulated in the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia’s Tadic decision—elements that are absent here.

First, to have an armed conflict, there must be organized parties, with command structures, capable of complying with the law of armed conflict. (Whether or not they do comply is irrelevant.) There is no evidence that Tren de Aragua, a criminal gang the intelligence community characterized as decentralized and lacking command-and-control structure, meets this requirement. Second, there must be some combination of frequent and/or severe hostilities that take the situation out of a mere law enforcement paradigm. Why this requirement? Because in war, the otherwise applicable human rights laws prohibiting arbitrary deprivation of the right to life and deprivation of liberty without due process of law simply do not govern. In other words, the law generally prohibits killing people except during a state of war, at which point only the enemy can be targeted. When every act of violence is treated as establishing a state of war, every killing of anyone defined as the “enemy” becomes justifiable.

And third, if everything I’ve said above denying application of a wartime paradigm is wrong, these killings would still be murder. The most fundamental principle of the law of armed conflict is that of distinction—the requirement that belligerents distinguish between combatants and civilians and target their attacks only against combatants. Drug runners, even if they are also terrorists, are not combatants and may not be treated as combatants unless they directly participate in hostilities or perform a continuous combat function. The administration has presented no evidence that the occupants of the Venezuelan boat were engaged in hostilities. That means that even if the current circumstances did constitute armed conflict—and they do not—these suspects were civilians and are therefore protected against arbitrary killing. In fact, the law does not only prohibit attacking civilians indiscriminately, it makes the targeting of them a war crime.

Patently Predictable

I agree with the countless analysts who have concluded that the boat strikes are illegal under any paradigm of international law. But unlike other commentators, I find the administration's purported legal justifications much less surprising because as unprecedented as this attack was, the justifications put forth have their roots in flawed, but long-standing and deeply embedded justifications and practices of the United States in the post-9/11 era.

The Bush administration’s response to the 9/11 attacks ushered in an era of war everywhere and always that continues today. War is illegal. If all states obeyed the UN Charter’s Article 2(4) prohibition of the use of force in international relations, and if all non-state actors refrained from the use of force (usually a crime under domestic law), there would be no wars. Obviously, a world without war is preferable. The Bush administration’s premise was not that war is good but, rather, that the enemy—which it defined in strategically vague terms as “terrorists”—transcended historical definitions necessary to determine who could legally be killed and under what circumstances.

Understanding why this kind of perpetual war is so legally damaging requires knowledge of how the international legal order distinguishes between peace and war. In peacetime, human rights law protects the rights to life and to be free from arbitrary deprivation of liberty. In war, these critical elements of human rights law are supplanted by rules that permit targeting of “enemy combatants” and deprivation of liberty based not on the targets’ conduct but, rather, on their mere status as “enemy.” In addition, civilians are subject to permissible killing as “collateral damage” so long as it is proportionate to the anticipated military gain, and subject to deprivation of liberty absent all the bells and whistles of due process that human rights law requires in peacetime. For these reasons, the law of armed conflict establishes limits on what is considered “armed conflict” and who can be considered “enemy” for purposes of both targeting and detention.

Following the 9/11 attacks, the Bush administration blew past these guardrails with a vengeance. Instead of limiting its definition of the “enemy” to al-Qaeda and the Taliban who harbored them, and instead of limiting its definition of war to the legal parameters establishing a state of armed conflict, the United States embarked on a “global war on terror” that dispensed with many of the legal restrictions that should govern. This had consequences in two distinct but related legal categories.

Jus ad bellum (the law regulating resort to force)

First, the Bush administration jettisoned traditional constraints on the right to use force in the first place. Instead of relying on well-established law limiting the use of force in self-defense to attacks that either had occurred or were “imminent,” the Bush administration redefined imminence to include threats that had not materialized—ones that were unformed and speculative. Under the Bush administration’s legal argument, the United States need not be limited to responding to the specific perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks; it could use force in response to “terrorism” writ large, on the theory that the mere existence of terrorism constituted an imminent threat.

A fuller understanding of what’s wrong with this picture can be gained by recognizing the reasons why “terror” or “terrorism” cannot logically, legally, and humanely be a subject of armed conflict. The laws of war apply to all parties to an armed conflict, whether they are states or non-state armed groups. Japan, Germany, the Irish Republican Army, and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia can surrender and promise not to do it again. Terrorism, however, is a tactic, not an entity. This is why wars are fought against proper, not common, nouns. This, of course, does not mean that terrorism cannot occur within armed conflict. In fact, international law already has a means of addressing it: the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols recognize and prohibit means and methods of warfare with the purpose of spreading terror among the civilian population.

Jus in bello (the law relating to conduct of hostilities)

Second, the Bush administration obliterated legal constraints on defining the enemy, and on defining membership within the enemy group, and thus on targetability and detainability of individuals. What started out as a war against al-Qaeda and the Taliban authorized by Congress morphed into justifications for the use of force against other allegedly “associated forces” in at least 14 countries with no discernable connection to the 9/11 attacks. The U.S.’s departures from existing legal constraints were further exacerbated by the fact that terrorism had—and still has—no agreed definition in international law.

Further, the U.S. employed a capacious definition of what constitutes “membership” in a terrorist organization, and then wrongly designated anyone considered a member as an “enemy combatant,” regardless of whether they participated in hostilities. In the Combatant Status Review Tribunals, association with al-Qaeda members was sufficient to merit designation as an “enemy combatant.” This could even include someone who unwittingly contributes to a terrorist organization. Similarly, instead of relying on characteristics directly related to belligerency, it became commonplace for U.S. forces in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere to consider gatherings of “military-age males” as enemy forces and, therefore, targetable. This is why the United States ended up bombing so many weddings in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Yemen.

U.S. practice, even under the early Obama administration, was to analyze civilian casualties in a conclusory manner by employing a presumption that anyone killed in a drone strike is a terrorist. This presumption served to minimize the apparent number of civilian deaths, which helped avoid accusations of noncompliance with the single most important principle of the law of armed conflict: the principle of distinction, which prohibits the targeting of civilians (noncombatants). But this definitional sleight-of-hand later proved ineffective: Reports of disproportionate “collateral damage” exposed the reality that civilians were being killed in drone strikes. President Obama ultimately issued a Presidential Policy Guidance (PPG) in 2013 to prohibit attacks absent a near certainty that civilians would not be harmed. In 2020, the first Trump administration rescinded the PPG.

In short, international law experts have denied that the laws of war can provide a basis for the Venezuelan boat attacks because, in the first instance, there is no war. But if they did apply, they would require U.S. forces to distinguish between combatants and noncombatants, and to direct attacks only against combatants. By blurring this distinction, previous post-9/11 administrations paved the way for flawed justifications for the use of lethal force by the Trump administration.

Dangerous Waters, but for Whom?

Past administrations’ arguments for an expanded “right to kill” have set the stage for this administration. The previous administrations’ arguments were wrong under international law, the current ones even more so. But if there has been no accountability for past administrations’ legal violations—indeed, if they seem to be snowballing—that does not mean there is no mechanism for enforcing the law now. It just comes from an unexpected place: Rather than restraining the officials who create the policies, it restrains the individuals who implement them.

That’s because individuals engaged in killing suspected drug runners—members of the military—can be personally liable for conducting illegal strikes, including the possibility of prosecution. Former Navy combat pilot and now Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.) has expressed these concerns, which have been expertly analyzed in the domestic legal context.

The personnel ordered to conduct such a mission are in the narrowest of spaces between a rock and a hard place. Under U.S. law, military personnel are permitted to disobey an illegal order and obligated to disobey a manifestly unlawful order. Violations of this obligation are crimes. At the same time, it is a crime to fail to obey a lawful order. International law, too, imposes legal risks on individuals who commit these acts. Everyone who’s heard of Nuremberg knows that “I was just following orders” is not a defense. In fact, the law is a bit more nuanced than that. Modern international law does not universally reject the “superior orders” defense; it is permissible for some kinds of order. But with respect to orders that are considered “manifestly unlawful” under Article 33 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the “superior orders” defense is unavailable. In the case of the U.S. strikes on Venezuelan boats, there is no question that an order to kill civilians is manifestly unlawful, whether during an armed conflict (where it may be a war crime) or outside an armed conflict (where it may be a crime against humanity).

The question, then, is whether U.S. military personnel who are ordered to conduct such strikes might put a stop to the administration’s illegal targeting by refusing to obey those orders, on the grounds that they fear personal liability under either domestic or international law.

In the past, military personnel could take some comfort in the fact that military missions are vetted for legal compliance in the planning stage by judge advocates general (JAGs). These positions still exist to ensure institutional independence in vetting proposed military missions, but Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, who has often expressed disdain for subjecting military forces to law, fired the top JAGs for the Army and Air Force. The top JAG for the Navy was retired. Consequently, the comfort zone for drone operators concerned about their personal legal exposure has narrowed even further. They may recognize that in the absence of lawyers’ input, they can no longer assume that their orders are legal. The fact that the strikes are so unprecedented is still more reason for them to doubt their lawfulness.

Of course, for military personnel to actually refuse orders, they must believe not only that the orders are illegal but also that they face meaningful personal risk by obeying them. It may seem unlikely that military personnel would be prosecuted in the United States, but some of the potential crimes—including murder—have no statute of limitations, and administrations do change. They may therefore face the risk of criminal prosecution in the United States under domestic law. More likely, however, those personnel may face legal risk when traveling abroad. Under the principle of universal jurisdiction, all states are empowered, and in some cases obligated, to search for and either try or extradite perpetrators of certain international crimes. (Universal jurisdiction is not only the purview of foreign nations; the United States has a statutory authority for exercising universal jurisdiction and has used it in the past.) Veterans of the Israeli Defense Forces recently found themselves in custody and under investigation in Belgium for war crimes committed in Gaza. Should unlawful U.S. military missions be undertaken in countries that are party to the International Criminal Court, U.S. personnel could be arrested abroad and fall within the jurisdiction of that court as well.

***

That the recent strikes on boats off the coast of Venezuela are illegal under international law cannot be seriously disputed. But returning to more rational, effective, and legal responses to threats—perceived and real—requires an honest assessment of where the Trump administration’s purported legal rationale comes from. And that means confronting the reality that the rationale builds on a long history of U.S. legal positions unsupported by international law. The flawed elements of the United States’s post-9/11 legal arguments—in particular, the unprincipled expansion of definitions that restrict who is a lawful target for the use of force, and under what circumstances—laid the groundwork for the Trump administration to claim that the boats’ passengers could be targeted because they are “terrorists” and that the use of force is appropriate because drug smuggling is an imminent threat or because the United States is already at war.

It is fitting to conclude with reference to one provision of U.S. law, the 2001 congressional Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) that was passed one week after the 9/11 attacks and that authorized the president to use “all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons [the president] determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons[.]” The authorization has been used to justify U.S. counterterrorism operations in 22 countries. Some of those operations had nothing to do with 9/11, al-Qaeda, or the Taliban. The AUMF’s passage was unanimous (98 to 0) in the U.S. Senate. In the House of Representatives, the vote was 420 to 1. The lone dissenter was then-Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.), who made brief but prophetic remarks:

The Congress needs to be careful not to embark on an open-ended war with neither an exit strategy nor a focused target …. As we act, let us not become the evil we deplore.

The U.S. attack that killed 11 people on a boat in the Caribbean Sea on Sept. 2 presented none of the elements that caused Congress to authorize the president to use military force after the 9/11 attacks. And yet, the unlawful policies and practices embraced by successive U.S. administrations in the aftermath of 9/11 are the foundation upon which the Sept. 2 attack was justified. It is not enough to point out the differences between then and now. What is needed is a repeal of the 2001 AUMF and a disavowal of theories, policies, and practices that led the United States to stray from the rules of the international legal order that it was so instrumental in establishing in the wake of World War II. These reforms are key to reclaiming a world that is more law-abiding, more peaceable, and more secure.

.jpg?sfvrsn=407c2736_6)