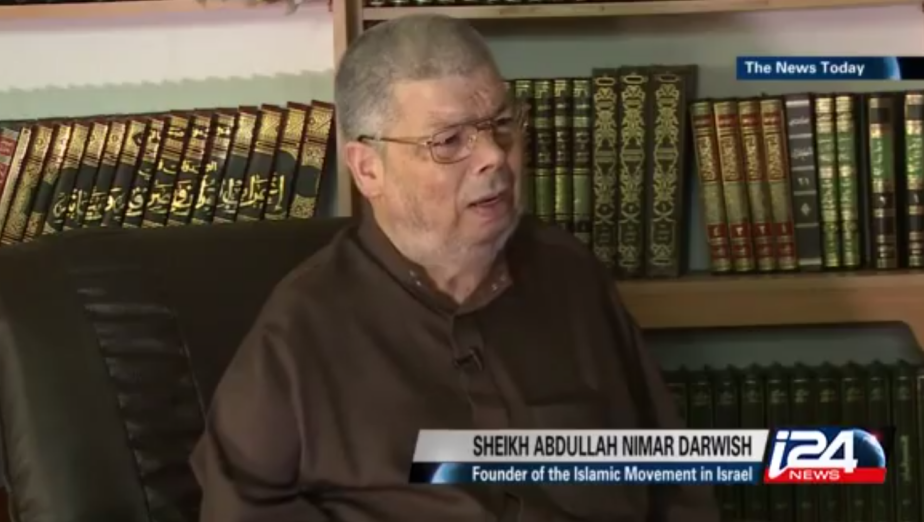

What Does an Israeli Islamist Sound Like? Meet Sheikh Abdullah Nimar Darwish

If you had told me a week ago that of the meetings I was going to have in Jerusalem, the one that would impress me most would be with an Islamist leader, I would have been, to say the least, skeptical. And I confess that I wasn't expecting much when Sheikh Abdullah Nimar Darwish entered the conference room in which we met last week.

If you had told me a week ago that of the meetings I was going to have in Jerusalem, the one that would impress me most would be with an Islamist leader, I would have been, to say the least, skeptical. And I confess that I wasn't expecting much when Sheikh Abdullah Nimar Darwish entered the conference room in which we met last week.

It's not just that Darwish is an Islamist—the founder of the Israeli branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, no less. He's also, to put it delicately, got a bit of a past. In the late 1970s, he formed an organization that conducted a string of violent attacks. And he spent a number of years in an Israeli prison. As I say, I wasn't expecting much.

Color me altogether wrong—and altogether repentant.

Sheikh Darwish is a fascinating man, and his movement is a fascinating movement. It is a recognizably democratic actor in a functioning democratic political system. Its commitment to acting within the law and within that system is sincere and long-standing. Indeed, since his time in prison, Darwish has consistently renounced violence, and he started a political movement that runs candidates for municipal and national Israeli office. The more radical wing of the movement broke off because he's too much of a squish. Running candidates who serve in the Knesset, after all, legitimizes Israel, they reason, and Darwish—unlike the more radical branch of the Islamic Movement—does not defend Hamas.

But what most fascinates me about Sheikh Darwish is his articulation of what I think is the single most eloquent and constructive formulation I have ever heard of the relationship between a Palestinian Arab, Muslim citizen of the Israeli state and the state in which he lives—a state that, after all, purports to be a Jewish state. He instructs his followers, he told us, to engage the Israeli state on the following basis:

I am a human being.

I am a Muslim human being.

I am an Arab human being, living on my land in the State of Israel.

I do not violate its laws.

I do not denigrate any of its citizens.

It is a remarkable statement, one that grows in power the more time you spend thinking about. It is a proud and unapologetic announcement of minority ethnic and religious identity. It is insistent on both the vitality of that minority's claims to its place in the society ("living on my land") and recognition that the minority community will not displace the larger society but is within it ("in the State of Israel"). It is accepting of the legitimacy and the authority of the state ("I do not violate its laws") and the need to live in harmony with others within it ("I do not denigrate any of its citizens"). It provides a basis, in other words, for engagement with and acceptance of the state and for demanding equal and fair treatment from it.

In an excellent Brookings paper on the Israeli Islamist movements, Lawrence Rubin last year described Darwish's transformation:

During his time in prison, he came to the realization that he needed to “work in the state of Israel by Islamic values without breaking the law.” Darwish convinced his 60-100 followers, almost all under the age of 25, to abandon their violent tactics and public calls for the creation of an Islamic state. He was elected leader of the movement in 1983 just before his release from prison. Over the years, Darwish would go on to write a series of works expounding upon his position to spread Islamic values among Muslim citizens within the confines of Israeli law. The idea that continued to evolve over time was that the movement would respect the laws of the state. These works, combined with essays in newspapers, collectively form the closest thing to a platform for the movement.

There's a lot to disagree with in Darwish's thinking. He defends the AKP in Turkey, for example. He gives more credence to the fact that Iran holds elections than I do. There's a social conservatism to the Islamic Movement with which I have few points of contact.

Yet there's also a lot to admire in what Darwish says and in the things he has done. He has worked with Orthodox rabbis to try to come up with governance principles for Jerusalem and the holy sites, and the principles he articulates seem to me smart and sensible and humane. He has consistently opposed violence. But most interestingly to me is his insistence upon Arab and Muslim political engagement in a political system in which Arab citizens constitute only 20 percent of voters and thus have no chance of taking power. This was the issue that split the Islamic Movement between Darwish's southern branch and the more radical northern branch. As Rubin writes,

Each faction justified its political position on religious-ideological grounds. The southern branch’s leader, Shaykh Darwish, argued that the Islamic Movement must adapt to local circumstances to serve the interests of the local community. In this case, Palestinian citizens of Israel would be best served through national representation. These interests again included enhancing their Muslim identity, improving the protection of holy sites, and fighting for equal rights for Arab citizens of Israel. Participation was permitted as long as the Muslim minority’s right to worship was protected. Meanwhile, the Northern branch, which shared the same goals, did not believe Islam sanctioned participating in a democracy, in which the majority could decide moral-legal issues, and especially ones that were hostile to Muslims. Shaykh Ra’id Saleh argued that parliamentary representation was irreconcilable with Islamic concepts because no secular legislative system (especially a Jewish Zionist one) could replace the source of divine legislation. In sum, the hard-liners’ ideological objection rested on their inability to reconcile the traditional Islamic outlook with the Jewish-Zionist nature of Israel as well as its Western, democratic institutions. It preferred, instead, to focus on the municipal level and work as independently as possible from the state.

Today, the sourthern branch of the Islamic Movement is part of the Joint List of Arab parties, which united together in the last election to run under a single party banner. Whatever folks may say about the supposed irreconcilability of Islamism, or sometimes even Islam, with democracy, it is an obviously democratic movement that has made important and admirable choices about how best to represent a minority community in the context of the Israeli political system.

In several days of meetings last week, there were few I left more hopeful than I entered. It's a bleak time in that country. Meeting with Darwish was a bit of an exception. He is a reminder that words like "Islamism" cover a lot of ground. In Israel, people like Darwish have a big role to play. An Israeli state with a keen eye on the future would be thinking very hard about how to engage with them over that role.

.jpg?sfvrsn=818c05df_5)

-1928c983-394b-444d-b1ec-f6590b7d9fee.jpeg?sfvrsn=78498e1e_7)