What the GBI Missed in Coffee County

At almost 400 pages, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation report on the Coffee County caper looks impressive. It’s not.

When a grand jury in Fulton County, Georgia, returned a sprawling indictment against Donald Trump and 18 co-defendants, the document included an astonishing allegation: The president’s legal team, aided by local officials and party loyalists, plotted to unlawfully copy and disseminate the state’s voting machine software in rural Coffee County, Georgia. They did this, the indictment alleges, as part of the larger alleged plot to overturn the legitimate results of an election that Trump had lost.

The Fulton County indictment charged four of the 19 original defendants with discrete crimes related to the voting systems breach in Coffee County. Two of the individuals charged, Scott Hall and Sidney Powell, recently pleaded guilty to criminal charges related to unauthorized access to voting systems. Two others, Cathy Latham and Misty Hampton, have pleaded not guilty and are awaiting trial with the other defendants.

Fulton County prosecutors, however, are not the only investigators interested in Coffee County. In August 2022, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI)—a state-level investigative department—began investigating allegations of computer trespass and other crimes related to unauthorized access to voting equipment in Coffee County.

The agency recently completed its 13-month investigation, culminating in a 392-page investigative report, which is now in the hands of Georgia’s attorney general, Chris Carr. He will decide whether to pursue charges based on its findings.

Earlier this month, Lawfare obtained a copy of the document and published it.

In the weeks prior to its publication, other media outlets reported on the contents of the document. The New Yorker wrote that the report paints a “robust picture” of Sidney Powell’s involvement in the breach. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution referred to the document as “exhaustive,” though an updated version of the story dropped that descriptor.

And for good reason.

To be sure, one could be forgiven for thinking initially that the GBI’s report on Coffee County is an authoritative account. It is, after all, nearly 400 pages long, and those pages summarize a voluminous body of evidence.

What’s more, in at least one notable respect, the report fills a previously unexplained gap in the record of the Coffee County saga.

But the document turns out to reflect a less vigorous investigation of the effort to unlawfully access the state’s voting machines than may initially appear.

The document suggests, rather, that the GBI did not investigate the Coffee County affair fully at all. The agency relied almost entirely on the previous work of civil litigants and the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol. It failed to seek interviews with key witnesses, and it omitted relevant evidence that is readily available in public documents.

The GBI’s investigation is difficult to evaluate comprehensively. The entirety of the report’s supporting evidence is not available publicly. Through various sources, Lawfare obtained some, but not all, of the attachments referenced in the report.

What’s more, the GBI’s strategy or organizational priorities as they relate to the Coffee County investigation are also not public. According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Attorney General Carr has said that his office will “continue to coordinate” with the GBI as he mulls potential charges. So it’s possible that the bureau completed additional investigative work that is not captured in the document.

With these caveats, however, what the report suggests about the GBI’s underlying investigation is sufficiently baffling as to warrant serious scrutiny. The quality of the GBI report matters because the Fulton County investigation focused on the Coffee County caper only insofar as it reflected the larger RICO conspiracy it alleged. The GBI report was supposed to look more broadly at crimes that may have been committed in what amounted to a theft of government property organized by insiders and outsiders alike.

In short, as a report, the document amounts to a tolerable summary of the readily available evidence. As an investigation that took more than a year to complete, it seems to reflect a badly inadequate effort.

The Investigation

The events that led the GBI to open an investigation began more than a year after the initial breach in Coffee County.

In February 2022, Marilyn Marks, the executive director of an election integrity group called the Coalition for Good Governance, publicly disclosed allegations related to the breach during a deposition of Gabriel Sterling. Sterling, the chief operating officer for the Georgia secretary of state’s office, was deposed as a part of a long-running civil suit, Curling v. Raffensperger, which Marks’s organization had been litigating since 2017. The suit focuses on the security of Georgia’s elections equipment, including potential vulnerabilities caused by unauthorized access to electronic voting systems.

During the deposition, an attorney for the Coalition for Good Governance played audio of a recorded phone call between Marks and Scott Hall, a bail bondsman from Atlanta.

On the call, Hall began to boast about the initial Coffee County breach. “I’m the guy that chartered the jet to go down to Coffee County to have them inspect all of those computers,” he told Marks. “We scanned every freaking ballot,” Hall said.

Notwithstanding this bold admission, state officials still remained skeptical even months later. In April of that year, Sterling spoke about the alleged breach during a public event at the Carter Center.

“There’s no evidence of that,” he said in reference to Coffee County—incorrectly. “It didn’t happen.”

It was only on Aug. 2, 2022, more than six months after Marks publicly disclosed her phone call with Hall, that the secretary of state’s office changed its tune and formally requested assistance from the GBI.

In a letter to GBI Director Vic Reynolds, the secretary’s office wrote that it had identified evidence of “suspected unauthorized access” to voting systems that took place “following the January 2021 runoff elections.” The letter articulates the GBI’s mandate: to investigate “possible election- and cyber-related crimes in Coffee County, Georgia.”

In the ensuing 13 months, a small team of special agents quietly pursued the Coffee County investigation—sort of.

In total, investigators interviewed only about 15 individuals. Many, if not most, of those interviews were conducted in under an hour. The bulk of the investigative work instead revolved around reviewing documents, emails, and deposition testimony, the vast majority of which derived from materials produced in discovery for the Curling litigation.

The resulting report, though it spans nearly 400 pages, merely summarizes the evidence reviewed by the GBI, mostly not original to the investigation itself.

The New Details

The overwhelming majority of the report’s narrative is familiar to anyone who has followed the Coffee County saga. It recounts in great detail the events of January 2021. I outlined these events in an earlier summary of the GBI report and an exhaustive account of the breach and the events that preceded it. For present purposes, the following mini-summary will do.

On Jan. 7, a local GOP chairperson, Latham, and the bail bondsman, Hall, accompanied a computer forensics team into the elections office in Douglas, Georgia. Inside, they were joined by two local elections officials, Hampton and Eric Chaney, and a former member of the elections board, Ed Voyles.

According to the GBI report, the forensics team—a group of employees with an Atlanta-based forensic data firm called SullivanStrickler LLC—had been hired by Sidney Powell, a lawyer working with Trump’s legal team. Over the course of several hours, the SullivanStrickler employees handled, scanned, and copied the state’s most sensitive voting software and equipment. They did this, the report alleges, without lawful authority.

Throughout the month of January 2021, similar breaches occurred on at least three other occasions, as additional outsiders were again given access to the state’s voting equipment. Forensic copies were subsequently accessed by more than a dozen individuals across several states, according to the GBI.

Taken as a whole, the report closely hews to facts developed in the Curling litigation, the raft of journalism that has been produced based on documents and information produced through that litigation, and the Fulton County indictment. Additionally, the GBI report draws on the final report of the Jan. 6 committee and the committee’s depositions with Powell and Rudy Giuliani.

The GBI report is not entirely derivative. Indeed, it divulges some interesting, if not ultimately essential, new details.

For example, we learn from the report that Jim Penrose, a former National Security Agency official who apparently “requested” SullivanStrickler’s work in Coffee County on Powell’s behalf, is represented by John Irving, a defense attorney with deep ties to Trumpworld. In Trump’s federal criminal cases, his legal team has previously referred some potential witnesses to Irving, who currently represents Trump’s co-defendant, Carlos De Oliveira, in the Mar-a-Lago classified documents case. According to campaign finance records, Irving’s firm, Earth & Water Law, has received more than $145,000 this year from Trump’s Save America PAC.

Or consider this nugget of information: When the GBI reached out to Hampton’s attorney, Jonathan Miller, to request an interview, Miller sought immunity on behalf of his client in exchange for her testimony. After the GBI declined that request, Miller followed up with a text: “Maybe we can work that out at a future time.”

Hampton, now indicted in Fulton County, has not publicly indicated whether she would be inclined to reach a plea deal. But her attorney’s previous requests for immunity could portend that she might be.

The document also highlights a July 2021 political fundraiser at Lin Wood’s South Carolina plantation. According to the report, Eddie Chaney—a friend of Latham who is not related to former elections board member Eric Chaney—told investigators that both Latham and Powell attended the fundraiser for Kandiss Taylor, then a candidate for the governorship of Georgia. It’s not a particularly consequential detail, as the event took place some six months after the breach. But it is interesting insofar as it highlights the relatively tight circle of Trump supporters who continued to work together after the 2020 election was over.

In an interview with Lawfare last month, Eddie Chaney stated that Powell did not attend the fundraiser—and that he never suggested otherwise to the GBI.

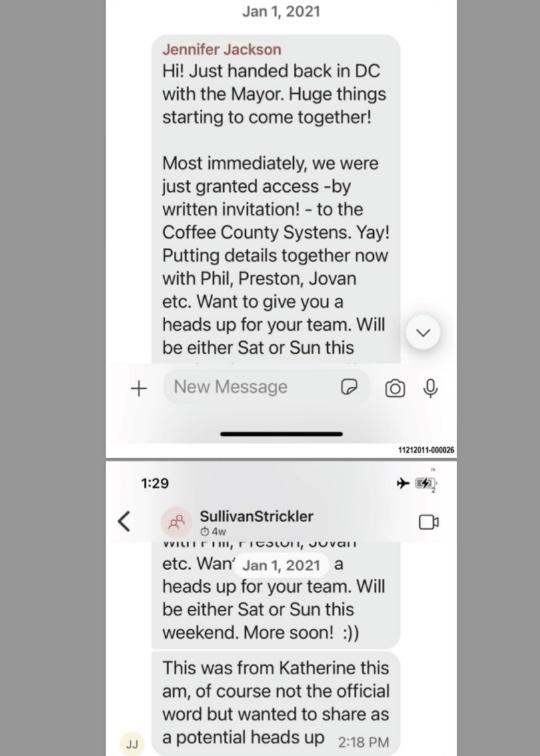

The document contains at least one significant factual development. As I have explained, a central mystery in the Coffee County saga once revolved around the so-called “written invitation” that purportedly authorized access to the county’s voting systems. Days before the Jan. 7 breach, Katherine Friess—an “election integrity” attorney for Trump who worked closely with Giuliani—messaged an employee of the Atlanta-based forensics firm SullivanStrickler: “Hi! Just handed [sic] back in DC with the Mayor,” she said. “Huge things starting to come together! Most immediately, we were granted access—by written invitation!—to the Coffee County Systens [sic]. Yay!”

SullivanStrickler employee Jennifer Jackson forwards a text message from “Katherine” to a group chat with other employees of the forensics firm. The GBI report identifies “Katherine” as Katherine Friess, an “election integrity” attorney for Trump who worked closely with Rudy Giuliani. Credit: Text messages obtained by Lawfare.

But the “written invitation” was never produced to litigants in the Curling case, and open records requests for such a letter produced no responsive documents. All of which raised several questions: Did a “written invitation” to access and copy voting machines in Coffee County actually exist? If so, who sent it? And what did it say?

In perhaps its most significant contribution, the GBI report provides answers to these questions. In June 2023, the agency seized the desktop computer used by Hampton during her tenure as elections supervisor. It subsequently extracted thousands of emails from the seized computer—emails that the county had insisted were unrecoverable for more than a year.

The tranche of emails included a purported “open records request” Hampton received from a Georgia attorney named Preston Haliburton on Dec. 31, 2020. In reply to Haliburton’s request, Hampton wrote as follows: “I will be speaking with my board, and per Georgia Law I do not see any problem assisting you with anything y’all need accordance to Georgia Law.”

Recovery of this “written invitation” helps shore up the strength of the putative criminal case in Fulton County by resolving potential ambiguity about whether the copying that occurred was authorized. I wrote in October that this language in the letter simply cannot be construed as an invitation for a third party to access and copy virtually everything in the county elections office. And the GBI report itself makes clear that there was no document “generated or agreed upon by Coffee County Officials granting outside access to their voting equipment.”

The Omissions

Notwithstanding these minor revelations, the document contains glaring factual omissions.

Consider, for example, its threadbare treatment of the circumstances that preceded the breach. The GBI’s account begins in mid-November 2020, when Powell and a group of Trump allies decamped to Lin Wood’s sprawling South Carolina plantation, Tomotley. Shortly after arriving, Powell hired SullivanStrickler for anticipated work in Michigan and Arizona, purportedly to “support litigation.”

The report then skips ahead to New Year’s Eve, when Haliburton and Hampton exchanged emails regarding the former’s “open records request” to Coffee County. The following day, Friess—the Trump attorney who worked closely with Giuliani—referred to Hampton’s reply as a “written invitation” to access Coffee County voting systems. One week after that, the report alleges, Latham escorted the SullivanStrickler team into the elections office.

Yet this account does not even attempt to answer certain key questions. Who devised the plan to access voting systems in Coffee County? When did the plan first arise? Who or what connected the then-president’s attorneys to several locals in rural South Georgia? The report bizarrely omits readily available facts that help connect these dots.

The most striking of these omissions concerns a sequence of events that occurred not in Coffee County but in Washington, D.C., approximately three weeks prior to the initial breach.

Over the summer, when Lawfare published a comprehensive account of the voting systems breach in Coffee County, events that occurred in D.C. around that time figured prominently. My account of those events—based on depositions, court filings, Jan. 6 committee transcripts, and documents obtained by Lawfare—focused on Latham’s arrival in the nation’s capital at a time when the Trump campaign faced a critical juncture in its quest to prove that the 2020 election had been “rigged.”

But it turns out there’s more to the story than I knew then.

Latham arrived just days before the now-famous Dec. 18, 2020, meeting at the White House, in which factions of Trump’s inner circle nearly came to blows over strategies to access voting machines.

According to deposition testimony before the Jan. 6 committee, one faction—which included Powell and former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn and the former CEO of Overstock.com, Patrick Byrne—sought the seizure of state voting machines by the federal government under a 2018 executive order.

Days before the Dec. 18 meeting in which Powell and others sought to persuade Trump to seize voting machines, a group of Trump allies holed up in a hotel in Washington, where they drafted executive orders that would have authorized such a plan. Both drafts, dated Dec. 16 and Dec. 17, respectively, referenced alleged voting irregularities in Coffee County as partial justification for the order.

Last year, emails obtained by Politico revealed that the draft orders were workshopped by multiple people, including Flynn and Phil Waldron, a retired Army colonel with ties to Allied Security Operations Group (ASOG). Friess, the attorney working with the Giuliani faction of the Trump campaign team, Christina Bobb, the One America News anchor and later a lawyer for Trump, and Bernard Kerik, an investigator working with the Giuliani legal team, also received emails discussing the draft orders.

According to Bobb’s testimony before the Jan. 6 committee, some members of that group drafted one version of the executive orders at the Trump International Hotel around Dec. 16, 2020.

But seizure of voting machines by way of executive order was not the only plan discussed by Trump allies at the Dec. 18 White House meeting, according to multiple Jan. 6 committee depositions.

Derek Lyons, a former deputy White House counsel who attended the meeting, told the Jan. 6 committee that Giuliani proposed an alternative: “voluntary” access to voting machines. According to Lyons, Giuliani’s point of view “was that in some way the campaign, I believe, was going to be able to secure access to voting machines in Georgia through means other than seizure.”

Powell corroborated Lyon’s account, telling the committee that Giuliani spoke of a plan to access voting machines in Georgia during the Dec. 18 meeting at the White House. (She recently repeated that claim in a recorded proffer interview with Fulton County prosecutors, according to the Washington Post.)

In other words, just a few weeks before l’affaire Coffee County took place, Giuliani was floating the idea in the White House of accessing voting machines in Georgia with insider help.

It remains unclear if Giuliani specified where in Georgia the campaign might obtain access to voting machines. But the day after the Dec. 18 meeting in which Giuliani discussed voting machine access, the former mayor of New York City seemed to have Coffee County on his mind.

Appearing on Steve Bannon’s “War Room” podcast on Dec. 19, 2020, Giuliani discussed his disappointment with the state’s governor, Brian Kemp, who had refused to call a special session of the state legislature to hear evidence of purported voter fraud. But Giuliani told Bannon that he was optimistic that Trump could reverse the results of the election in Georgia without Kemp. “We’ve got a big project working in Georgia right now, right around behind his back. He doesn’t know what’s going on,” Giuliani said.

“We met pretty much on and off all day yesterday,” Giuliani explained. “And starting this morning, there’s a completely different strategy. The strategy is going to focus a great deal on some evidence we have about some of these machines that could throw off these states in a matter of maybe a one- or two-day audit.”

It was important for the campaign to get access to machines, Giuliani said, because “machines get your attention, because you can’t fight the machine.” He continued: “If they would allow this, I could put on television a machine and I can show you I can change the vote 14 different ways. I can show you where they re-ran the vote in Coffee County, Georgia. They got three different results, three different times… We can show you these votes belong to Trump, they don’t belong to Biden.”

A few days after Giuliani appeared on Bannon’s podcast, according to the transcript of Giuliani’s deposition before the Jan. 6 committee, Powell sent an email to Giuliani, Mark Meadows, and Trump’s assistant, Molly Michael.

The Dec. 22, 2020, email read: “Also be advised Michigan trip was not set up properly on ground with locals. Team is there with no access. It has cost us great expense that should be reimbursed by Rudy’s funding. Georgia machine access promised in meeting Friday night to happen Sunday has not come through” (emphasis added).

When Jan. 6 committee investigators confronted Giuliani with this email, he claimed that he could not remember making such a promise during the Dec. 18 meeting at the White House. But it could be a reference, he said, to “negotiating with one of the [elections] boards for access to some of the machines.”

Pause here over the key facts: the draft executive orders to seize voting machines that cited Coffee County specifically; the raucous Dec. 18 White House meeting in which Giuliani allegedly proposed “voluntary access” to voting machines in Georgia; Powell’s Dec. 22 email alluding to Georgia voting machines, which Giuliani said could be a reference to negotiating with an elections board for access. Not a single one of these facts is mentioned in the GBI report.

Nor does the report deal with the apparent arrival of Latham in Washington, D.C., right around the time that the Trump campaign was on the hunt for access to voting machines in Georgia.

The GBI report names Latham as a subject of its investigation. And it notes that Latham admitted under oath that she stayed at the Willard Hotel in D.C. for an unspecified period sometime in December 2020. She had been invited to D.C., she said in a deposition, to go on a “tour” hosted by a woman named “Juliana” Thompson.

“We [got] to see the Christmas trees, and I got to go to the Bible Museum,” Latham explained during her 2022 deposition.

But the report does not mention numerous facts that suggest Latham might have had other business in the nation’s capital besides going to the Bible Museum.

Consider, for example, a Dec. 17, 2020, text exchange between Latham and Marks, the executive director of the election security organization that initiated the Curling suit. In messages reviewed by Lawfare, Marks explained that her organization was involved in litigation to move away from the use of Dominion Voting Systems in Georgia. She asked if Latham might be available to chat about election security issues.

Latham replied that evening: “I am in D.C. right now and am about to meet with IT guys.”

During her deposition in the Curling suit, Latham asserted her Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination in response to questions about this text. The former public school teacher also declined to answer when asked if she met with anyone who was not with her D.C. tour group. “I’m going to plead the Fifth on that,” she replied.

Notably, the Powell and Giuliani factions of the Trump campaign worked with a group of so-called election security experts and analysts who were variably referred to as the “tech team” or “cyber guys” in multiple Jan. 6 committee depositions.

The group included Waldron, who was listed as a key member of the Giuliani camp’s “tech team” in a “strategic communications plan” that mentioned Coffee County. There was also Penrose, the former National Security Agency official who requested SullivanStrickler’s work in Coffee County. They were joined by Conan Hayes, an ex-pro surfer turned election conspiracy theorist, and the America Project’s Todd Sanders, both of whom would later gain access to data copied from Coffee County.

According to Byrne’s Jan. 6 committee testimony, some members of the “tech team” worked on postelection campaign matters out of a block of hotel rooms at the Trump International Hotel in D.C., which is located just a few blocks down the road from the Willard Hotel.

And Latham was not the only Trump supporter staying at the Willard Hotel around that time. The landmark hotel famously served as the “command center” for the legal arm of the Trump campaign led by Giuliani in this period of time. The rooms were reserved by Friess and paid for by Kerik, the former police commissioner of New York City who worked for the Giuliani legal team as an investigator. Indeed, Kerik later sought reimbursement for the rooms from the Trump campaign.

According to his testimony before the select committee, Kerik paid for the room of an unnamed “whistleblower” from Georgia who traveled to the Willard to meet with Giuliani sometime during the postelection period. The “whistleblower,” he said, had been brought to the hotel by William Ligon, a Georgia state senator, and Haliburton, the Atlanta attorney who would later initiate Hampton’s “letter of invitation” on New Year’s Eve.

Kerik did not specifically identify the whistleblower by name. But later that month, on Dec. 30, Latham appeared alongside Giuliani and other Trump surrogates at a legislative hearing in Georgia chaired by Ligon. At that hearing, Latham claimed whistleblower status as she testified about the alleged “problems” with Dominion Voting Systems machines in Coffee County. Haliburton, who was listed as “counsel of record for the Giuliani legal team,” also represented Latham at the hearing.

What’s more, a review of social media posts and photos, and interviews with a participant on Latham’s D.C. trip, reveals that the former Coffee County GOP chairwoman crossed paths with at least three top Trump allies during her December 2020 trip to D.C.: Rudy Giuliani, Sidney Powell, and Michael Flynn.

In an interview, Jason Shepherd, a conservative Georgia attorney and assistant professor at Kennesaw State University, confirmed that Latham joined a tour group in D.C. over a two-night period from approximately Dec. 16 to Dec. 18, 2020. Shepherd, like Latham, stayed at the Willard Hotel during that time as a part of a tour organized by Julianne Thompson, a Georgia GOP strategist who is married to a prominent Republican lawyer, Jason Thompson. The group of roughly 20 people included conservative personalities like Rose Soma Tennent, a TV and talk radio show host, and Juanita Broaddrick, a retired nurse who had accused former President Bill Clinton of rape during his presidency.

A highlight of the trip, Shepherd said, included a group visit to the Bible Museum.

Cathy Latham, pictured in the top left photo, with a Washington, D.C., tour group at the Willard Hotel. Credit: Julianne Thompson on Facebook.

But the Bible Museum did not seem to be the only thing on Latham’s mind that December, according to Shepherd. “Looking back, she would disappear a lot,” he recalled about Latham’s behavior on the trip.

Shortly after the group returned to Georgia, Shepherd learned one reason for Latham’s disappearance: She was “meeting” with Sidney Powell, he said. “She was kind of bragging about it after we got back from the trip.”

In September, the Daily Beast reported on a 2022 interview with Latham, in which she touted meeting Powell during her trip to D.C. According to the report, Latham said she snapped a photo with Powell and Flynn after she ran into them at the Trump Hotel. At the time, Powell was technically working as Latham’s attorney; Latham had volunteered as a plaintiff in one of Powell’s “Kraken” suits in Georgia. But Latham claimed the run-in at the Trump Hotel was the only time she ever crossed paths with Powell, according to the Daily Beast.

A newly unearthed photo appears to memorialize Latham’s December 2020 meet-up with Powell and Flynn at the Trump Hotel. In the photo, Latham poses with Powell, Flynn, and two fellow travelers in the D.C. tour group.

Cathy Latham, far right, with Michael Flynn and Sidney Powell at the Trump Hotel in mid-December 2020. They are joined by Michele Braddock-Beagle and Patti Peach. Credit: Michele Braddock-Beagle on Facebook/@Z_Everson on X.

The photo, originally published to Braddock-Beagle’s Facebook page, was subsequently posted to Twitter, now called X, by Forbes journalist Zach Everson on Dec. 18, 2020. At the time, Everson was cataloging happenings at the Trump Hotel for his website, 1100 Pennsylvania. The precise date on which the photo was taken remains unclear, but a comparison of the time stamps on the posts and the dates of Latham’s trip suggests that it was likely taken on Dec. 16 or Dec. 17, 2020.

Flynn and Powell were not the only members of Trump’s inner circle with whom Latham met in December 2020. According to a combination of photos and social media posts, Latham attended what she described as a “meeting” with Giuliani sometime on the evening of Dec. 17, 2020—the same evening that she texted Marks about meeting with “IT guys.”

In one post, Facebook user “Cathy Marie” commented in reply to Broaddrick, one of the right-wing personalities who joined the 2020 tour group: “Here we are in DC in December 2020 when we had dinner in that pub with Julianne and Jason. I came and had dessert after meeting with Mayor Giuliani.” An attached photo shows Latham seated next to Broaddrick at a restaurant.

Broaddrick responds to the post, “Cathy Alston Latham I remember you. Thanks.” The “Cathy Alston Latham” account tagged by Broaddrick reroutes to the profile of “Cathy Marie.”

A person familiar with Latham’s social media usage confirmed that “Cathy Marie” is one of Latham’s Facebook profiles.

Facebook user “Cathy Marie” comments on a post by Juanita Broaddrick. The photo, from left, shows Cathy Latham with Broaddrick at a restaurant. Credit: “Cathy Marie” and Juanita Broaddrick on Facebook.

A separate post by the host of the D.C. tour, Julianne Thompson, suggests the date of the dinner. In a Dec. 17, 2020, post on Facebook, Thompson chronicled what the tour group did that day, noting that they visited the White House and the Bible Museum before heading to dinner at a pub, Daniel O’Connell’s Irish Restaurant.

In other words, around the time members of Trump’s team holed up at the Trump Hotel to draft executive orders that specifically refer to Coffee County as partial justification for seizing voting machines, two of the main proponents of those draft orders met the then-Coffee County GOP chair at the Trump Hotel. One of those people, Powell, would later pay for the forensic work carried out in Coffee County in January 2021.

Meanwhile, according to Latham’s Facebook post, Giuliani met with the then-Coffee County GOP chair one day before he allegedly proposed “voluntary access” to voting machines in Georgia during the Dec. 18 White House meeting. The day after that, Giuliani discussed accessing Coffee County voting machines on Bannon’s podcast. And several days later, Powell sent an email that alluded to a “promise” to access voting machines in Georgia, which Giuliani told the Jan. 6 committee could be a reference to negotiating with an elections board for access to machines.

None of these facts appear in the GBI report. All of them were available based on either the publicly accessible records or voluntary interviews with participants in the events in question.

To be sure, the nature and substance of the apparent meetings between Latham and top Trump allies remain unclear, and not everyone is eager to share details of what happened. An attorney for Latham did not respond to requests for comment. An attorney for Powell declined to comment. A spokesperson for Giuliani did not respond to requests for comment.

That the GBI does not appear to be aware of these facts, however, suggests either that the agency took an unduly narrow approach to the scope of its investigation or that it did not conduct a thorough investigation.

There are other omissions from the report. Consider, for example, the Dec. 30 legislative hearing at the Georgia state capitol. As previously noted, Latham claimed whistleblower status at that hearing as she testified about purported problems with Coffee County elections technology.

The attorney who represented Latham at the hearing, Haliburton, also appeared as “counsel of record” for the Giuliani legal team. Haliburton, a former heavyweight boxer who has repeatedly touted an old photo of himself with Trump on Instagram, told the group of state legislators that he chose not to make some of his elections research public for fear of “retaliation.” But he didn’t shy away from expressing who he believed to be the rightful winner of the state’s electoral votes: “Donald Trump won Georgia,” Haliburton said.

Giuliani, for his part, appeared in person to deliver remarks on behalf of the Trump campaign. “Let us examine the machines,” Giuliani said. “We’ll find out really fast if this was the cleanest election in history or the biggest scandal in terms of voting in the history of this country.”

To discuss the purported insecurity of Georgia’s voting systems, a former treasure hunter named Jovan Hutton Pulitzer appeared as an “expert” for the Giuliani legal team. During his presentation, Pulitzer falsely claimed that he had hacked into an election “poll pad.” He also claimed that, if he had access to ballots cast in the 2020 election, he would be able to tell which ballots were “fraudulent” with “100 percent” accuracy.

Rudy Giuliani, center, speaks to Georgia state legislators at a hearing on Dec. 30, 2020. Looking on, from right: Attorney Ray Smith, now one of Giuliani’s co-defendants in Fulton County; Kandiss Taylor, the current chairperson of the Georgia GOP; Cathy Latham, then Coffee County GOP chair; Preston Haliburton, attorney for Latham and the Giuliani legal team; Bob Cheeley, an attorney who is now indicted in Fulton County alongside Giuliani, Latham, and Smith. Credit: Jovan Hutton Pulitzer on Facebook.

The Dec. 30 legislative hearing does not appear in the GBI report. That is odd considering the report’s account of what happened next: The day after Latham, Giuliani, Haliburton, and Pulitzer were all in the same place at the same time to give false information about supposed problems with Georgia voting machines at a formal legislative hearing, Haliburton sent the “open records request” that prompted Hampton’s so-called “written invitation” in response. In relaying this “invitation” to a SullivanStrickler employee on Jan. 1, 2021, Friess added that she had just landed back in D.C. with “the Mayor” and that she was “putting details together” with Waldron, Haliburton, and Pulitzer.

Less than a week later, Latham escorted the SullivanStrickler team into the Coffee County elections office. According to the GBI report, both Waldron and Pulitzer later sought access to the copied data. And Giuliani told the Jan. 6 committee that an expert who gained access to machines in Coffee County gave him a report on the data. That expert, Giuliani said, “probably was Phil Waldron.”

The GBI apparently never sought interviews with Waldron or Pulitzer or Haliburton or Giuliani. In other words, the GBI report tells part of the story of what these four were up to—but it leaves out a big chunk.

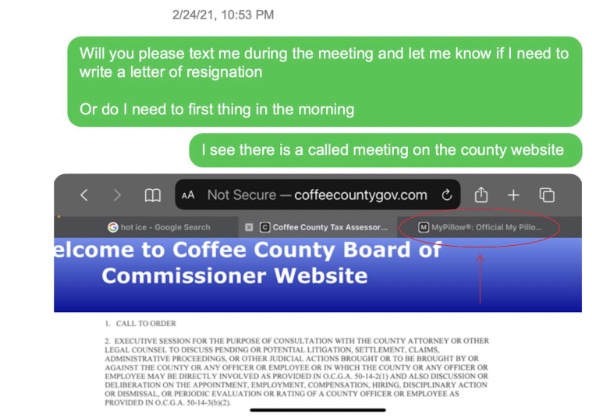

Then there is the mystery surrounding the arrival of Mike Lindell’s private jet in Douglas, Georgia, on Feb. 25, 2021, just hours after Hampton had been pushed out of her job as elections supervisor, purportedly for falsifying her time sheets. Lindell is the founder and CEO of MyPillow and a prominent election conspiracy theorist.

According to testimony summarized in the GBI report, Eddie Chaney, a Coffee County local who works part time at the airport, told investigators that he pumped fuel for Lindell’s jet when it arrived in Douglas on Feb. 25, 2021. The pilot of the plane advised him that Lindell had been en route to Texas from Washington, D.C., when he abruptly decided to land at the Douglas airport. According to Chaney, Lindell was there to attend an event at Atkinson County High School.

The GBI report does not note that Lindell has offered a different reason for landing in Douglas. Last year, after the Washington Post first reported on Lindell’s visit to Coffee County, Lindell claimed that he had traveled to Douglas to meet with pillow entrepreneurs.

The report also does not mention several peculiar coincidences that preceded Lindell’s arrival. On Feb. 24, 2021, the day before Lindell landed in Coffee County, text messages produced in litigation appear to show that Hampton had been contacted by Kurt Olsen, a lawyer who has represented Lindell in various election-related matters. Olsen’s name appears on notes Lindell brought to a meeting at the West Wing in January 2021 that contained references to “martial law” and “foreign interference in the election.”

Later in the evening on Feb. 24, according to text messages produced in the Curling case, Hampton had the MyPillow.com website open in her browser.

In a deposition, Hampton pleaded the Fifth when asked if she spoke to anyone who represented Lindell prior to his arrival in Douglas.

A photo sent via text message from Misty Hampton to Eric Chaney on Feb. 24, 2021, appears to show the MyPillow website open in one of Hampton’s browser tabs. The next day, Mike Lindell’s plane landed for two hours in Douglas, Georgia. Credit: Text messages obtained by Lawfare.

Less than 24 hours later, Lindell’s plane touched down for about two hours at the municipal airport in the rural South Georgia town. Earlier that day, according to a report from ABC’s Jay O’Brien, Lindell visited Trump’s Mar-a-Lago club in Palm Beach, Florida, where he met with Trump staffers.

During a deposition in the Curling case, Hampton pleaded the Fifth when asked if she had ever met Lindell. She also invoked her Fifth Amendment rights when asked if she gave Lindell anything she had taken from the Coffee County elections office.

Lindell, for his part, was not identified as a subject of investigation in the GBI report. And he continues to insist that he visited Douglas in February 2021 on MyPillow-related matters. Contacted for comment about the GBI report, Lindell said he was “probably” in Douglas around that time to visit one of his product vendors. He could not recall attending an event at the high school but noted that he has given speeches at high schools in the past.

Lindell declined to provide Lawfare with contact information for any MyPillow vendors located near Douglas, Georgia. He also claimed that he does not know Hampton.

“Maybe she likes MyPillow,” he said.

Why It Matters

A conspiracy to unlawfully copy and distribute Georgia’s most sensitive voting systems data, carried out at the behest of the then-president’s legal team and aided by local allies, as alleged in the Fulton County indictment, constitutes a serious crime.

Indeed, according to some election security experts, the breach in Coffee County could have dangerous implications for future elections. Though Coffee County’s servers were replaced following the breach, Georgia continues to use the same software that SullivanStrickler copied and that other individuals later distributed. “Adversaries may use the software in disinformation campaigns or study it to learn how to subvert its operation through malware, reprogramming, or disabling defenses,” Kevin Skoglund, the chief technologist for Citizens for Better Elections, warned in a court filing last year.

All of which calls for a serious investigation.

To that end, two individuals who have pleaded guilty to reduced charges in Fulton County—Hall and Powell—have already faced something of a reckoning. Two more—Latham and Hampton—await trial.

But the Fulton County investigation has always been limited as a vehicle to resolve questions about criminal culpability for an alleged crime carried out largely in a rural county some 200 miles away.

To be sure, District Attorney Fani Willis’s use of the state’s racketeering statute allowed her to expand the probe outside the usual jurisdiction of Fulton County. But as the Lawfare team observed back in August, each of the indictment’s six discrete counts related to the Coffee County scheme make reference to facts that seem intended to support the Fulton County district attorney’s claim of jurisdiction.

The indictment asserts, for example, that Powell entered a contract with SullivanStrickler in Fulton County for the purpose of advancing the object of the conspiracy—and that Latham, Hall, and Hampton aided and abetted that firm’s employees in accessing Coffee County’s elections office and voter data during the initial breach on Jan. 7, 2021. In this sense, the indictment aims to tie the Coffee County charges to Fulton County, even though the gravamen of the alleged crime occurred hundreds of miles away.

These jurisdictional concerns may be one reason, and there may be others, why Willis seemingly declined to seek charges against the 30 unindicted co-conspirators listed in the Fulton County indictment, some of whom helped coordinate the Coffee County breach or disseminated the data retrieved, according to the indictment.

In addition to her jurisdictional limitations, Willis has relatively limited resources compared to that of statewide or nationwide law enforcement agencies. The ambition of her indictment of Trump and 18 others already carries risks. Including the full scope of possible charges against those involved in the Coffee County escapade would threaten to turn the district attorney’s otherwise “sprawling” indictment into a completely unwieldy one.

For this reason—compounded by the apparent lack of interest of the Department of Justice and the special counsel’s office—it necessarily fell to the GBI to thoroughly and completely investigate the alleged crimes in Coffee County. The agency’s investigative report suggests that it has not done that.

Memo to Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr: You have been ill served by your investigative department. There’s still a lot of work to do.