When Extremists Stormed the Capitol and Got Convicted of Seditious Conspiracy

In 1954, four Puerto Rican nationalist terrorists stormed the Capitol and shot five congressmen. The incident also produced an interesting Second Circuit opinion.

“In Washington D.C., ruthless fanatic violence erupted in the halls of Congress,” the news opened.

Extremists had burst into the Capitol. They made a beeline for the chamber, looking for members of Congress. It was “pandemonium.” The anchor declared that the attackers had earned “the evil distinction of having perpetrated a criminal outrage almost unique in America’s history.” He decried the attack as “wanton violence that shocked and stirred the nation” but “only did harm to the cause” the attackers purported to represent.

Sound familiar? It should—except that the attack in question took place on March 1, 1954, at the hands not of #MAGA extremists but of Puerto Rican independence radicals.

In the hours and days after the Jan. 6 insurrection in the Capitol, commentators and journalists rushed to label the siege as “unprecedented” or “never-before-seen.” Any number of commentators have noted that the Capitol had not been stormed since the War of 1812.

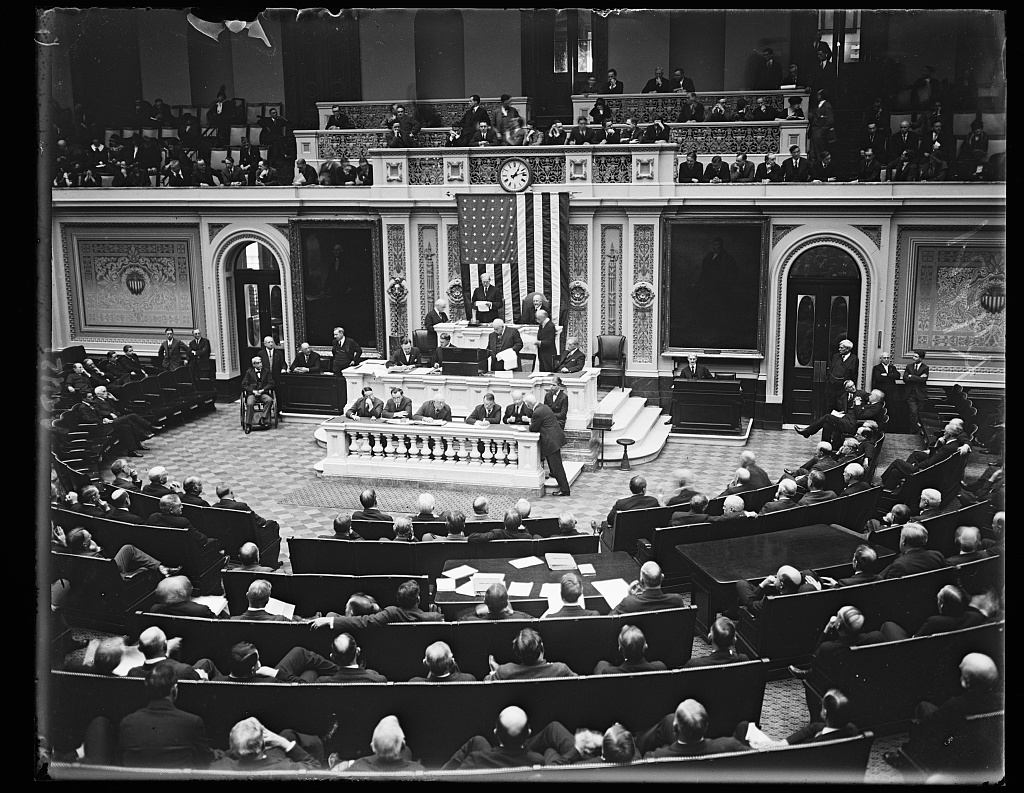

Members of the 83rd Congress might beg to correct the record on this point. On a March afternoon in 1954, members and staff scrambled for cover when four Puerto Rican nationalist terrorists stormed into the Capitol and began “spraying the place with bullets.” The attackers shot five congressmen and caused what a clerk later described as “bewilderment” on the House floor at this “surrealistic” attack. Amazingly no one died, but 35-year-old Michigan Rep. Alvin Bentley, who was shot in the chest, “was never really the same.”

And just as commentators are now talking about the seditious conspiracy statute as a potential charge against some of the Jan. 6 rioters, the Justice Department charged the four attackers, along with 13 other members of the Puerto Rican nationalist group, with seditious conspiracy. Four pleaded guilty and 13 were convicted at trial. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit rejected an appeal from 12 of the defendants, although President Carter did ultimately commute the sentences of all four assailants.

The 1954 attack has gotten short shrift in coverage of the “Stop the Steal” riot on the Hill. But the Justice Department and the Second Circuit’s handling of the case has some real relevance to the current moment. Bryce Klehm, Alan Rozenshtein and I wrote immediately following the attack that a Justice Department decision to charge the 2021 rioters with seditious conspiracy or other “political charges” would “send the strongest message about the severity of the behavior on display.” And it looks like the department may be pursuing that route. It has already charged a militia leader with conspiracy, though not seditious conspiracy. And Acting U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia Michael Sherwin told reporters last week that his office “organized a strike force ... whose only marching orders from me are to build seditious [conspiracy] charges related to the most heinous acts that occurred in the capitol.” Sixty-five years ago, the Justice Department took exactly that approach toward the Capitol insurrectionists, and the Second Circuit’s opinion specifically deals with an attack on the Capitol. That opinion contains some law potentially relevant to the present situation: It spells out the scope of the statute and unambiguously affirms its constitutionality, in a decision cited in a major later seditious conspiracy case.

The 1954 attackers had hoped the shooting would make a “grand political statement.” Lolita Lebron, Rafael Cancel Miranda, Andrés Figueroa Cordero and Irving Flores Rodriguez were members of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico (PNPR). The PNPR had a history of violence that predated the Capitol attack. It had launched an unsuccessful rebellion on the island on Oct. 27, 1950, and four days later, tried but failed to assassinate President Harry Truman in D.C.

The 1954 shooters took a day-of train from New York, where the cell had its base, to Washington. At 2:30 p.m. the foursome burst into the Capitol Building and began firing on the House floor. A House page explained later that “[a] lot of the Congressmen just heard pop-pop-pop-pop going on, and they thought it was firecrackers.” House Speaker Joe Martin later wrote in his memoir that it was “the wildest scene in the entire history of Congress.” Capitol Police—aided by D.C. Metropolitan police, staffers, and Rep. James Van Zandt, a World War II veteran and Navy rear admiral—arrested three of the shooters on-site, and police detained the fourth later in the day.

House pages, meanwhile, carried the wounded congressmen out to ambulances. An overseer for the House pages recalled trying to call hospitals to tell them a shooting happened in the Capitol Building: “I said, ‘There’s been a shooting in the House of Representatives. You got to send an ambulance.’ He said, ‘Kid, you shouldn’t joke about things like that,’ and hung up the phone.” The phone operators at the hospitals weren’t the only ones incredulous after the shooting. In a comment with a striking resemblance to the lies promulgated by some House Republicans after the 2021 riot, Puerto Rican Resident Commissioner Antonio Fernós-Isern labeled the attackers as “communist dupes,” telling the Baltimore Sun, “Can it be the doing just of Puerto Rican Nationalists? ... Who benefits? Certainly not Puerto Rico.”

A grand jury in the Eastern District of New York indicted the four shooters and 13 other members of the PNPR for seditious conspiracy. The indictment didn’t just cover the D.C. shooting, but alleged a “single continuous conspiracy operating at least from Sept. 1950 to May 1954.” During that period, recounted the Second Circuit, the group “committed spectacular acts of violence”: the 1950 “armed uprising” in Puerto Rico, the botched assassination attempt of President Truman, the D.C. shooting, and an unfulfilled “master plan for revolution in Puerto Rico encompassing occupation of military garrisons and attacks on American forces stationed on the Island.” The defendants belonged to different cells of the party, referred to in the Second Circuit opinion as “juntas.” Most of the defendants, including all the shooters, belonged to the New York junta. A few others named in the indictment had roles in the Chicago junta or were dual-hatted between one of the U.S. juntas and the junta back in Puerto Rico.

Twelve of the defendants appealed their trial court convictions to the Second Circuit, but the appeals court rejected the appeal in a short opinion and reaffirmed the lower court’s decision. Wrote the Second Circuit, the PNPR, “once a political party, had abandoned hope of achieving Puerto Rican independence through legitimate political processes in favor of overthrowing American authority in that commonwealth by force of arms and by violence.”

Two parts of the Second Circuit are particularly notable for present purposes: First, the ruling articulated an expansive vision of what a “conspiracy” is under the seditious conspiracy statute; and second, it held that the statute itself doesn’t run afoul of free speech protections.

Only four of the 17 named in the indictment actually stormed the Capitol and did the shooting. Some of the 13 nonshooters asked the Second Circuit to rule that they should not be tried alongside the people who shot actual congressmen. The trial judge made a mistake in refusing to sever their indictments from the indictment of the four gunmen who shot the congressmen, they argued. This faction argued that the four years of crimes, distributed between three juntas, wasn’t one single conspiracy and that the congressional attack amounted to a separate conspiracy in which they weren’t involved. But the Second Circuit was unpersuaded. Judge Jerome Frank wrote, “We reject the theory that that attack was a separate conspiracy, and we agree with the trial judge that evidence of that attack was admissible against all the defendants.” Per Frank, the trial judge can make the call about whether severance is merited, and “where the charge against all the defendants may be proved by the same evidence and results from the same series of acts, an upper court will not interfere with that.”

What’s the upshot of Frank’s ruling here? The “conspiracy” part of “seditious conspiracy” can apply to a whole bunch of people. Frank wrote that “the Washington attack illustrates the close coordination of activity between juntas.” In other words, the New York and Chicago juntas, though almost 800 miles apart, participated in a single conspiracy.

Put that in the present context, in which Acting U.S. Attorney Sherwin told NPR that he’s looking at the rioters for “communication ... affiliation and a command and control” in order to build seditious conspiracy cases, and the Lebron decision articulates a vision of what that standard might be for geographically disparate cells of a group.

The Second Circuit held that the government “successfully linked each of the appellants with the conspiracy,” including some with more tenuous links to the headliner crime. This included someone who “gave orders to Chicago junta to obtain weapons for Congressional attack,” someone who “attended and participated in discussions of planned acts of violence,” someone who was merely a “procurer of arms,” and even the “Minister of Propaganda,” who served as “editor and publisher” of the New York party newspaper and who merely “attended New York junta meetings at which violence was discussed.” In other words, even those not physically present for the violence can be tried as parties to the broader conspiracy.

The second interesting part of the Second Circuit opinion comes in response to an appeal from the minister of propaganda. A collection of the appellants “contend[ed] that their prosecution for criminal conspiracy violates the right of political expression protected by the First Amendment.” The opinion notes that “[t]he claim is particularly urged by defendant Jose A. Otero, whose party role, in part, was that of editor and publisher rather than of gunman, and whose last party position, before his arrest, was that of Minister of Propaganda.” The opinion laconically dispenses with the Otero objection: “We think such a contention has been rejected by the Supreme Court in United States v. Dennis.”

Dennis v. United States is a 1951 case that dealt with an appeal from the general secretary of the U.S. branch of the Communist Party for his conviction of violations of the Smith Act, a 1940 anti-sedition law that has been pared down in the intervening years. Dennis upheld the constitutionality of the Smith Act, arguing for a flexible interpretation of the “clear and present danger test.” Applying the test as a “rigid rule,” the court held, would “paralyze our Government in the face of impending threat by encasing it in a semantic straitjacket.” Per the majority, certain interests can outweigh the interests of free speech and “[o]verthrow of the Government by force and violence is certainly a substantial enough interest of the government here.” The Smith Act, the majority held, doesn’t target “discussion” but is instead “directed at advocacy” for the overthrow of the government, thus it meets the constitutional bar. The majority noted that success or failure of the insurrection doesn’t weigh on the propriety of government intervention, writing that “[c]ertainly an attempt to overthrow the Government by force, even though doomed from the outset because of inadequate numbers or power of the revolutionists, is a sufficient evil for Congress to prevent.” With Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969, the court threw out the “clear and present danger test,” and along with it overturned Dennis, replacing the test with the more restrictive “imminent lawless action” standard. So it’s reasonable to expect that someone who was merely publishing propaganda could not, without more, be treated as part of a seditious conspiracy today.

Yet the Second Circuit’s free speech jurisprudence from Lebron popped up more than 40 years later in the court’s other major seditious conspiracy opinion. The Second Circuit in 1999 considered and rejected an appeal from Sheik Omar Abdel-Rahman and some of his followers for their conviction under the seditious conspiracy statute. Rahman, known as the “Blind Sheikh,” was convicted of seditious conspiracy for masterminding the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. Rahman challenged his conviction by bringing a “generalized First Amendment challenge” to the seditious conspiracy statute.

The 1999 Second Circuit panel noted that Rahman didn’t exactly come up with a novel legal theory on this point: “Our court has previously considered and rejected a First Amendment challenge to Section 2384. See United States v. Lebron.” The panel charts the evolution of the Supreme Court’s free speech jurisprudence from Dennis onward but holds that the more rigid protections of Brandenburg and other cases don’t mean much for the Blind Sheikh: “The prohibitions of the seditious conspiracy statute are much further removed from the realm of constitutionally protected speech than those at issue in Dennis and its progeny.” The reason is that “[t]o be convicted under [the seditious conspiracy statute], one must conspire to use force, not just to advocate the use of force. We have no doubt that this passes the test of constitutionality.” As a result, “Rahman’s generalized First Amendment challenge to the statute is without merit.” In other words, after 40 years and a bunch of major Supreme Court free speech decisions, the Second Circuit ends up in more or less the same place it did in Lebron: The seditious conspiracy statute doesn’t itself violate the First Amendment.

The Lebron decision is not a perfect match for the Capitol insurrectionists of 2021. For one, it’s important to keep in mind that there are two different buckets of potential 2021 seditious conspiracy defendants: On the one hand, there are those who stormed the Capitol and are likely quite vulnerable to seditious conspiracy prosecution; on the other, there are those who might have played a role in coordinating the riot but weren’t physically present in the Capitol. And the fact pattern of the Stop the Steal breach differs in some respects from what happened in 1954—for example, the Capitol rioters did not belong to groups that tried to assassinate the president of the United States. It’s also unlikely that it will be a district court in the Second Circuit that will try a 2021 rioter for seditious conspiracy, meaning that the Lebron decision will probably not be a controlling precedent for any trial court. But either way, the Second Circuit’s Lebron opinion helped to fortify the constitutionality of the statute and carves out a vision of “conspiracy” that might be of use to federal prosecutors today. Reporters might continue to call the storm “unprecedented,” but it’s unlikely that a judge would take the same view.

.jpg?sfvrsn=3792d97a_5)