A Better Way to Talk About Risk

Editor’s Note: As the United States reduces its emphasis on counterterrorism and focuses more on China in particular, policymakers have emphasized the need to accept more risk. What, however, does risk actually mean? National Defense University’s Kim Cragin examines current frameworks for thinking about risk and assesses how to think about risk and the threat of terrorism.

Daniel Byman

***

A consensus has emerged among U.S. civilian and military officials that the United States must prioritize deterring Chinese aggression. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, in his confirmation hearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, noted that China represents “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted,” and Adm. Samuel Paparo, commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, has expressed concern to Congress about China outpacing U.S. defense production. Elbridge Colby, the undersecretary of defense for policy, has noted that, to facilitate the U.S. focus on China, Washington will rely more on allies “to help address military shortfalls both vis-à-vis Beijing as well as in other theaters against other potential opponents, particularly Russia, Iran, North Korea, and terrorists.” In other words, the United States will accept some risk from Russia, Iran, North Korea, and terrorist groups to deter China.

It may seem like a throwaway phrase, “accept risk.” It’s not. If risk is the potential for something bad to happen, then the United States is accepting that something bad might happen elsewhere to prevent something bad from happening in Asia. One of those “elsewheres” could be the homeland. The U.S. military has played an instrumental role in disrupting terrorist attacks against the West since 9/11. A shift away from countering terrorism logically increases the risk of such an attack. It might be possible to alleviate some risk through heightened border security. However, these trade-offs have yet to be fully explored.

Part of the challenge is that U.S. national security decision-makers are not great at calculating strategic risk. Frank Hoffman made this argument recently in Joint Force Quarterly, “Risk: A Weak Element in U.S. Strategy Formulation.” Hoffman reviewed memoranda written during the transition between the Bush and Obama administrations. He also examined three U.S. military interventions: the initial invasion of Iraq, the raid against Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan, and the withdrawal from Afghanistan. Hoffman concluded that strategic risk was not well understood. In the case of the August 2021 evacuation from Afghanistan, this miscalculation led to a disastrous outcome.

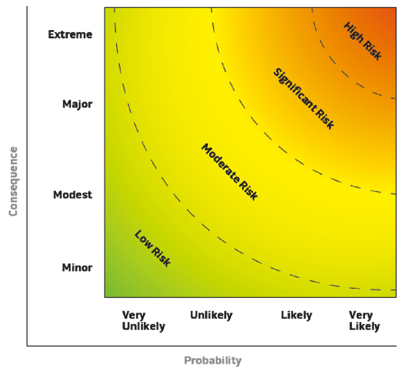

The U.S. military also has acknowledged this shortcoming. To address it, the Joint Staff published the Joint Risk Analysis Methodology (JRAM) in December 2023. The JRAM provides guidance to military officers on how to calculate and articulate strategic risk. The logic is built on the tactical construct of “risk to mission” and “risk to force.” The JRAM contains a risk matrix that uses a chart with consequences on the y-axis and probability on the x-axis to depict low, moderate, significant, and high risk (Figure 1). It also provides time horizons for risk analyses: near-term (0-3 years), mid-term (2-7 years), and long-term (5-15 years).

Figure 1. Joint Risk Analysis Methodology.

The JRAM does not work well for dynamic risks like terrorism. Terrorist threats are volatile and analysts can rarely forecast beyond two years, making the time horizons of three, seven, and 15 years unrealistic. For example, the commander of Central Command, Gen. Michael Kurilla, testified in March 2023 that the Islamic State would be able to rebuild its capabilities to attack the United States within two years, once U.S. forces withdrew from the Levant.

A shorter time horizon also dovetails with the evolution of Islamic State-Khorasan Province (IS-K) in Afghanistan. Soon after U.S. forces withdrew from Afghanistan, Christine Abizaid, director of the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), testified before the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs. Abizaid articulated the consensus of the U.S. intelligence community that IS-K no longer had the ability to conduct external operations. Approximately 15 months later, IS-K plotted against the FIFA World Cup. Authorities prevented this attack, but IS-K’s efforts to carry out foreign attacks have continued. It has since attacked and plotted against Russia, Germany, Austria, France, and the United States. This suggests that a time horizon for assessing risk of even two years, much less 15 years, might be a stretch.

Beyond time horizons, the characterization of risk in the JRAM—low, moderate, significant, and high—can be problematic due to different civilian and military interpretations. Much has been written about the approval process for counterterrorism operations. Simply put, U.S. military tactical commanders weigh the threat posed by a particular Islamic State fighter, such as a recruiter or financier, against the risk-to-force presented by the proposed operation. This calculation gets made at each higher echelon within the U.S. military until, often, it gets to the National Security Council and the president. Former National Security Adviser John Brennan described the process as follows:

If our counterterrorism professionals assess, for example, that a suspected member of al-Qaida poses such a threat to the United States to warrant lethal action, they may raise that individual’s name for consideration. The proposal will go through a careful review and, as appropriate, will be evaluated by the very most senior officials in our government for a decision.

The “very most senior officials” are civilians. They do not read the JRAM. They understand low, moderate, significant, and/or high differently than military commanders. A civilian might be told a particular threat poses a “high risk” and interpret it through the prism of their own experiences in their day-to-day lives, which are often focused on political calculations. A military commander, in contrast, might say “high risk” and likewise mean it in the context of their day-to-day lives with an entirely different meaning. Hoffman identified this lack of a shared perspective of risk as a significant hindrance in the run-up to the evacuation from Afghanistan. It also exists in counterterrorism.

Equally important, counterterrorism requires iteration, a concept somewhat absent from the JRAM. The find-fix-finish methodology necessitates persistent strikes or raids; otherwise, terrorist groups will regroup and rebuild. On March 13, for example, U.S. forces killed the Islamic State’s chief of global operations, Abu Khadijah. The Islamic State has had six chiefs of global operations, and five leaders, since its inception in June 2014. But it’s not just about decapitation. Find-fix-finish requires persistent strikes on terrorists responsible for external operations. Without these strikes, terrorist groups have proved capable of reconstituting enough to execute an attack. Since August 2021, the U.S. military has averaged two such strikes or raids per quarter worldwide against the Islamic State, with the average increasing to five strikes in the past six months. This battle rhythm has been sustained by a dedicated force based overseas. The United States can pull out this force, but it entails accepting some degree of strategic risk.

U.S. defense planners and senior officials need a better way to calculate and articulate strategic risk for counterterrorism. It should incorporate reasonable time horizons, take into account the need for iteration, and have common-sense definitions of low, medium, significant, and high risk. Beginning with time horizons, if military planners’ default is 15 years for the long term, then counterterrorism time horizons should be shortened as follows: short term (3-9 months), medium term (10-21 months), long term (22-36 months). Those with relevant authority and oversight responsibilities should insist on projections that fit within these time horizons for the assessment, development, and execution of U.S. counterterrorism policy.

Characterizations of risk also should be common sense and understandable to civilians. They should include calculations of political and diplomatic risks as well as military risks. For example, strikes against IS-K present a significant risk to force (or asset) due to the tyranny of distance and the terrain, but strikes on the Houthis in Yemen—designated a foreign terrorist group in January 2025—also entail a risk to force (or asset). The Houthis have reportedly shot down six MQ-9 Reaper drones since March 15. This prompts the question: Why Yemen and not Afghanistan? It is hard to see how the Houthis pose a greater threat to the U.S. homeland than IS-K. But the Houthis’ attacks arguably represent diplomatic risks if they threaten U.S. allies and partners—which they have by targeting Israel and the Gulf states. Elected officials should insist that strategic risks and trade-offs of this nature are articulated clearly and are not bogged down in hyperbole, military jargon, and narrow concepts of risk.

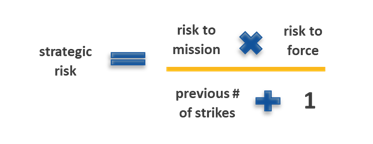

Finally, calculations of strategic risk as it relates to counterterrorism should account for strikes or raids (or the absence thereof) undertaken in the past 3-9 months. The discussion should be less about presence (e.g., where U.S. forces are based) and more about battle rhythm. That is, the assessment of strategic risk should increase the more time extends without a strike or a raid against the same threat. The equation in Figure 2 depicts this conceptual approach to strategic risk for counterterrorism.

Figure 2. Strategic risk for counterterrorism.

Admittedly, the iterative nature of counterterrorism is why it is sometimes, scornfully, referred to as “mowing the grass.” This equation likewise perpetuates that logic. It builds in a requirement for persistent strikes or raids against foreign terrorist threats with the expectation that the threat will continue indefinitely. It does not offer a solution. It is agnostic as to where U.S. forces reside as long as they can sustain the find-fix-finish methodology. Nevertheless, it presents a clear and concise articulation of strategic risk as the military shifts its attention to the Indo-Pacific. After all, as a former official once told me, “You have to at least mow the grass; otherwise, your house gets pretty bad.”