Exploring Ukraine’s Armed Neutrality or Nonalignment: Legal and Policy Considerations

Armed neutrality or nonalignment can ensure Ukraine’s security outside NATO, but with robust Western security obligations and Russian concessions.

Ви можете також прочитати цю статтю українською мовою тут.

Talks on ending the Russia-Ukraine War seem to have reached an impasse. The peace proposals put forth by Ukraine and Russia reveal a significant gap in their positions, leading many observers to conclude that a negotiated settlement is currently not feasible, including Anastasiia Lapatina recently in the pages of Lawfare. The third round of negotiations between the parties on July 24 expectedly did not bring any visible breakthroughs. Russia is pursuing its summer offensive, apparently being optimistic that continuing its aggression will make Ukraine more amenable to its maximalist demands. At the same time, many Ukrainian and Western analysts argue that, under the circumstances, Ukraine has no choice but to fight until it denies Russia success on the battlefield and essentially forces it to negotiate seriously or acquiesce to a tacit ceasefire. All of this raises the risk of a multiyear war of attrition—one with uncertain outcomes and an increasing death toll.

As others have suggested, increasing economic and military pressure on Russia is an essential ingredient for ending the war on terms that will ensure an independent, secure, and prosperous Ukraine. At the same time, it is crucial not to abandon diplomacy to achieve this result sooner rather than later. Namely, the continuing robust pressure needs to be combined with exploring creative diplomatic solutions. The proper combination of sticks and carrots may lead to a decent negotiated settlement.

One of the key points of disagreement between Ukraine and Russia that, if addressed, could create an opening in the negotiations is whether Ukraine will maintain its aspirations for NATO membership or become a nonaligned or neutral state. The last time the parties had meaningful talks about ending the war was in Istanbul in 2022, precisely the discussions about neutrality that helped achieve some progress in the negotiations. The major question is whether Ukraine can ensure its security and independence while remaining neutral or militarily nonaligned, and whether Ukraine can keep its political alignment and security cooperation with its Western partners. Armed neutrality or nonalignment can make it possible, but only if Russia backs down from its own expansive vision of Ukraine’s neutrality and Western partners agree to a robust security arrangement for Ukraine.

2022 Istanbul Talks and Russia’s Neutrality Demands

Soon after the 2022 full-scale invasion, Ukrainian and Russian delegations conducted multiple rounds of negotiations, first in Belarus and then in Istanbul, resulting in the so-called Istanbul Communique and multiple drafts of a treaty on Ukraine’s permanent neutrality and security guarantees. While Russians had various sweeping demands, including on the recognition of occupied territories, demilitarization of Ukraine, and cultural issues, according to Ukraine’s lead negotiator, David Arakhamia, Ukraine’s neutrality “was the biggest thing for them.” Indeed, the Istanbul Communique—drafted by Ukraine and reportedly provisionally accepted by Russia as a framework for negotiations—put permanent neutrality and related security guarantees to Ukraine at the center of the talks and did not mention the Russian cultural, demilitarization, and recognition demands, providing that a planned treaty would mention the parties’ intentions to resolve the issues related to Crimea and Sevastopol only through negotiations in 10-15 years. The primary purpose of the latest draft of a multilateral treaty exchanged between the parties was also to establish Ukraine’s permanent neutrality that would be recognized and guaranteed, including with a pledge to come to Ukraine’s collective self-defense, by the five permanent (P5) members of the United Nations Security Council and potentially other states. The draft envisioned mutual obligations between Ukraine and the guarantors regarding the maintenance of Ukraine’s permanent neutrality.

Early in the negotiations, Russia presented its maximalist starting position aimed at making Ukraine defenseless. However, as the Russians began to experience more and more setbacks on the battlefield, their position started softening significantly. Still, considering that Ukraine was in a difficult situation in early 2022, it was also forced to consider concessions at that point.

While agreeing in principle with the concept of permanent neutrality, the Ukrainian delegation insisted on security guarantees, including from the P5 members of the UN Security Council, which would oblige the guarantors to come to Ukraine’s defense with their armed forces if it were attacked again. Russia reportedly agreed to such guarantees in principle. Still, it requested that any actions under them would require a joint decision of all guarantors, essentially giving it the veto over military assistance to Ukraine. Ukraine informed Russia that it was a nonstarter, and it remained unclear whether this issue could have been resolved with further negotiations, but the previously agreed Istanbul Communique reflected the Ukrainian version of the guarantees. Regardless, the latest draft treaty that was exchanged between the parties, and which reportedly landed on Putin’s desk, contained the following Article 5 on security guarantees:

The Guarantor States and Ukraine agree that in the event of an armed attack on Ukraine, each of the Guarantor States, after holding urgent and immediate consultations (which shall be held within no more than three days) among them, in the exercise of the right to individual or collective self-defense recognized by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, [Russian revision: on the basis of a decision agreed upon by all Guarantor States], will provide (in response to and on the basis of an official request from Ukraine) assistance to Ukraine, as a permanently neutral state under attack, by immediately taking such individual or joint action as may be necessary, [Ukraine revision: including closing the airspace over Ukraine, the provision of the necessary weapons], using armed force in order to restore and subsequently maintain the security of Ukraine as a permanently neutral state.

If the Russian revision was excluded, the wording would be somewhat stronger than Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, which requires NATO members to take only those actions that they “deem necessary,” though the security guarantees would not apply to Crimea and certain areas of the Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts to be defined by the parties.

In addition to the Russian intransigence, however, Ukraine’s Western partners were unwilling to agree to such security guarantees because they apparently did not consider the protection of Ukraine to be a sufficiently important interest to warrant pledging to fight for the country in the future. Additionally, joining the treaty would essentially mean accepting one of the Russian demands to NATO before the war, namely, a legally binding obligation not to expand NATO to Ukraine.

In addition to demanding Ukraine’s permanent neutrality, the Russians insisted on, among other things, sweeping limits on the Ukrainian armed forces, or what they call “demilitarization.” Although they walked back slightly the numbers they initially demanded, the Russians were still asking for unacceptable caps on the Ukrainian armed forces in the latest draft, for example, 85,000 on personnel and 342 on tanks. At the same time, Ukraine insisted on maintaining a standing peacetime army of approximately 250,000 personnel (excluding the reserves, the National Guard, and other military forces outside the Armed Forces of Ukraine), comparable to its prewar strength, and on having the number of weapons it considered appropriate at that time (for example, 800 tanks). Importantly, Ukraine had these numbers in mind, considering the realities of early 2022 and on the condition of obtaining the security guarantees mentioned above. It was again unclear whether further negotiations could have pushed the Russians to back down on this issue. Importantly, although the Istanbul drafts envisioned caps on Ukrainian forces, as I explain below, such limitations have nothing to do with the legal status of permanent neutrality, and one can argue that they are actually antithetical to it.

After hesitating initially, Russia also agreed to Ukraine’s position in the latest draft, which stated that its permanent neutrality would be compatible with potential membership in the European Union and even EU peacekeeping operations. Importantly, in earlier drafts, Russia wanted to foreclose Ukraine’s participation in the EU’s “military component,” mutual aid and assistance commitments under Article 42(7) of the Treaty on European Union, and not to join any EU actions and decisions against Russia and its national interest. However, considering Ukraine’s observation that Russia had no objections to the participation of neutral states, such as Austria and Malta, in the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy, Russia dropped that request. The latest draft only provided a caveat that any EU-related activities will comply with the status of permanent neutrality under the planned treaty.

Although Russia continued to insist on changes to Ukrainian cultural and language policies, as well as other sensitive issues, it placed less emphasis on its territorial demands compared to its initial position. Indeed, the latest draft did not include any provisions on recognizing Russian sovereignty over the territories it occupied unlawfully. The Istanbul Communique provided that the parties would strive to diplomatically resolve their disputes over Crimea and Sevastopol within 10-15 years. It might have been that the parties were agreeing to disagree on this question in 2022. According to Ukraine’s lead negotiator, David Arakhamia, the Russians also reportedly stated that they were ready to vacate at least some territories they occupied as a result of the 2022 full-scale invasion. Reading the Istanbul Communique together with the latest draft treaty suggests that the security guarantees would have applied to many territories under Russian control at that time, including those in Kharkiv, Kherson, and Zaporizhia oblasts, implying that the Russians would need to withdraw their forces from these areas. Although there was a risk of Russian deviation from this vision down the road, still, this shows that Ukraine’s neutrality may have been more important for Russia than territorial questions.

Russia’s demands in today’s negotiations are, in many respects, a continuity of the position it took in the 2022 Istanbul talks. However, one of the key differences is that it now demands the recognition of its sovereignty not only over Crimea and the Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts but also over the Kherson and Zaporizhia oblasts that it does not fully control, including their administrative centers. Any potential discussions on neutrality should be conditioned on Russia dropping these unreasonable recognition demands. Considering the Istanbul experience and prior Russian strategy of prioritizing Ukraine’s non-bloc status over territorial control, including in the Minsk process, this scenario should be seriously explored in the negotiations. Among other things, Ukraine should point the Russians to their consistent statements that they had no problems with neutral Ukraine within its 1991 borders.

Crucially, as explained below, the Istanbul drafts revealed that Russia has a rather expansive interpretation of the concept of permanent neutrality that exceeds its usual requirements. In addition to demanding unreasonable caps on the Ukrainian armed forces that are antithetical to permanent neutrality, Russia sought significant limitations on Ukraine’s defense cooperation with the West that is necessary for the Ukrainian defence capabilities and that can comply with permanent neutrality. This contributed to Ukraine’s concerns that neutrality may not ensure its security following the end of the war. As explained below, neutrality is meant to make a state secure, not defenseless.

Meaning of Neutrality and Nonalignment

At its core, neutrality is the legal status of a state that does not participate in an international armed conflict between belligerent states. When there is an international armed conflict, non-parties to it are considered neutral by default, unless they choose to aid the belligerents in a manner that makes them parties to the armed conflict. The law of neutrality outlines the relevant rights and duties of neutrals and belligerents in the case of an international armed conflict.

At the same time, a state may decide to commit to neutrality in all future armed conflicts, essentially preemptively refusing the option of becoming a belligerent, by declaring so-called permanent neutrality under international and domestic law (for example, Switzerland, Austria, Malta, and Costa Rica). (For a comprehensive analysis of permanent neutrality, see Pearce Clancy’s excellent thesis.) A state may also declare a mere policy of neutrality, conveying its intention to remain neutral in future conflicts without any legal constraints under international and/or domestic law (for example, Sweden before the end of the Cold War, and Ireland today).

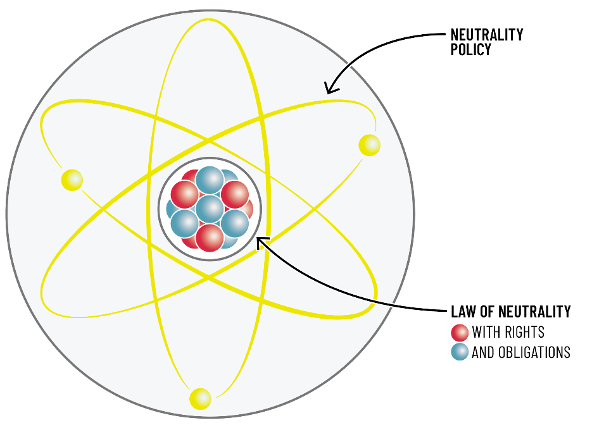

The policies of neutrality of states, including those that are permanently neutral, vary and may voluntarily exceed the requirements under the law of neutrality. In case of permanently neutral states, neutrality policy helps ensure predictability and credibility of permanent neutrality, taking into account the international context of the moment. Swiss guidance illustrates the connection between the law and policy of neutrality with the image of an atom, where the law of neutrality is the nucleus, while “neutrality policy orbits flexibly around [it], like an electron shell, although there is limited room for movement” (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Relations between the law of neutrality and neutrality policy. (Source: Swiss guidance)

At the same time, nonalignment and non-bloc status generally refer to a voluntary state policy of remaining outside of military blocs and alliances. Unlike the policy of neutrality, it does not necessarily imply remaining neutral in future armed conflicts and complying with the law of neutrality. Sweden and Finland transitioned from a policy of neutrality to a nonaligned status following the end of the Cold War, before they joined NATO. For example, in its 2020 policy statement, Sweden stated that it “will not take a passive stance if another EU Member State or other Nordic country suffers a disaster or an attack,” which could have been interpreted to include the exercise of the right to collective self-defense. Considering its flexibility, this type of policy may be more attractive for Ukraine and its Western partners. Still, it may be harder for Russia to swallow due to the lack of meaningful legal constraints regarding participation in armed conflicts and because it can be easily changed, as seen in the cases of Finland and Sweden. The remainder of this section addresses legal constraints under the law of neutrality and the concept of permanent neutrality, including the demands Russia made during the Istanbul talks that exceed these requirements and even contradict the concept of permanent neutrality.

Law of Neutrality During Wartime

The law of neutrality encompasses both customary and treaty law, including the 1907 Hague Convention V and the 1907 Hague Convention XIII. Although these conventions are outdated in some important respects, and state practice evolved beyond them, they still reflect the key principles of neutrality. Considering patchy state practice, the exact contours of neutrality are often difficult to pinpoint. Among other things, outlawing the use of force in international relations, as enshrined in the UN Charter, has put significant pressure on the relevance of strict notions of neutrality, especially in conflicts with a clear aggressor and a victim of aggression.

The core obligations of a neutral state include the duties of non-participation and impartiality. The non-participation duty means an obligation not to provide military assistance to either party in an armed conflict, including via direct military intervention or the supply of weapons. Also, a neutral state must prevent its territory from being used as a base for military operations or any belligerent activity by the parties to an armed conflict, whether through invasion or transit. As a corollary to that, the neutral territory is inviolable, meaning the belligerent cannot conduct hostilities on it, and no collateral damage to it is permitted.

The broader duty of impartiality obliges a neutral state to treat both belligerents equally by not providing a military advantage to either of them. Nowadays, impartiality is better understood as the principle that informs the implementation of the neutral’s non-participation rights and duties, rather than being an expansive limitation in and of itself. It also relates only to a military advantage and does not mean ideological, political, moral, and economic impartiality, including not preventing a neutral state from condemning the unlawful use of force by one of the belligerents. As a testament to this, for example, Switzerland has long considered economic sanctions against a violator of international law to be compatible with the law of neutrality because they have “the function of restoring order and thus serve the peace.”

Western military assistance to Ukraine to defend itself against Russian aggression sparked a scholarly debate about whether these states can provide assistance without violating neutrality obligations or becoming belligerents. There are two main approaches to this. The first is the so-called qualified neutrality, providing there is no need to apply the law of neutrality equally to the victim and the aggressor, especially when it is clear that aggression occurred, like in the Russia-Ukraine War (for example, see Michael N. Schmitt, Wolff Heintschel von Heinegg, Oona Hathaway and Scott Shapiro, and Department of Defense Law of War Manual). Under this approach, the supply of weapons and intelligence to the victim of aggression is compatible with the neutral status. The second approach, known as strict neutrality, maintains that the law of neutrality applies equally in respect of all belligerents regardless of who unlawfully initiated the armed conflict, especially when the supporting states do not exercise the right of collective self-defense of the victim of aggression to reduce risks of becoming a party to the armed conflict (for example, see Raul (Pete) Pedrozo and Michael Bothe). Relying precisely on strict neutrality, Russia argued that Western assistance to Ukraine violated the law of neutrality.

This divergence in Western and Russian understandings of the law of neutrality has important implications for Ukraine’s potential neutrality. Namely, the question is what a neutral Ukraine would be able to do in case Russia unlawfully attacks a NATO member. Although joining the conflict on the side of NATO members, including by allowing its territory to be used for their military operations, would be foreclosed in such a case—unless Ukraine adopts a more flexible nonalignment policy akin to the one Sweden pursued in the past—considering patchy state practice, it is not entirely clear what precise scope of assistance it would be allowed to provide under the law of neutrality. If qualified neutrality is adopted in this respect, then Ukraine’s assistance may include the type of support its Western partners currently provide to it, such as offensive weapons and intelligence sharing. Another approach would utilize a blueprint of assistance that neutral states, such as Ireland and Austria, have provided to Ukraine, including nonlethal materiel, financial, political, and humanitarian support. At the same time, Switzerland abstained from providing military assistance to Ukraine, while still supporting the EU’s sanctions regime.

Importantly, the law of neutrality applies only insofar as there is a pending international armed conflict. Considering the prohibition of the use of force under the UN Charter, participation in a the conflict between other states would be legal only on the side of the victim of aggression via the exercise of the right to collective self-defense under Article 51 of the UN Charter. That said, a state can voluntarily agree to certain neutrality obligations during peacetime and limit its right to act in collective self-defense of other states by adopting so-called permanent neutrality. This is the status that was discussed during the 2022 Istanbul talks, but with Russia demanding many additional requirements that are unrelated to, or even contradict, it.

Permanent Neutrality During War and Peace

One of the key elements of permanent neutrality is a state’s obligation to be neutral in future armed conflicts between other states. When an armed conflict occurs, a permanently neutral state must comply with the law of neutrality and refrain from entering the conflict as a belligerent. In modern international law, this essentially boils down to renouncing the neutral state’s right to act in collective self-defense of a victim of aggression and abstaining from providing it with military assistance incompatible with the law of neutrality. However, this does not preclude assistance from third parties to the permanently neutral state under attack, including in collective self-defense.

Besides the commitment to remain neutral in future conflicts, permanent neutrality also usually entails peacetime obligations to abstain from any acts and agreements “which would render the fulfilment of obligations of neutrality impossible should the armed conflict occur” (emphasis added). There is no agreed-upon list of acts and obligations that would make maintaining neutrality impossible. Indeed, permanent neutrality is often defined on a case-by-case basis in the respective treaties or unilateral declarations, the substance of which may vary and include bespoke arrangements. According to Paul Seger, any limitations of permanent neutrality should be interpreted restrictively, as they impose limitations on state sovereignty. Still, some scholars argue that there is an ordinary meaning of permanent neutrality that includes certain de minimis default elements, unless a bespoke neutrality instrument supersedes them. Relatedly, the Istanbul drafts referred to the “international legal status of permanent neutrality,” apparently implying the de minimis approach under international law. Such an open-ended reference to the highly ambiguous body of law may lead to disagreements in practice, including providing Russia a potential opportunity to claim casus belli (although unlawful) by arguing the violation of the concept of permanent neutrality in its most restrictive understanding. Thus, any potential instruments of Ukraine’s neutrality should strive to be precise in defining its contours.

A common limitation often imposed by permanent neutrality is abstention from joining military alliances, such as NATO, as exemplified by the cases of permanent neutrality of Switzerland, Malta, Austria, and Turkmenistan. However, membership in economic organizations such as the EU, including mutual aid and assistance commitments under Article 42(7) of the Treaty on European Union, is compatible with neutrality, as confirmed by the EU membership of Austria, Malta, and Ireland. As mentioned earlier, Ukraine and Russia appear to have agreed on this in the latest Istanbul draft. Additionally, nothing prevents a permanently neutral state from entering into defense agreements and cooperation with other states, short of a full-fledged military alliance, provided they comply with the parameters of its neutrality. Also, a neutrality instrument can explicitly allow certain defense agreements, as, for example, Costa Rica’s neutrality declaration did in respect of the Rio Treaty on Reciprocal Assistance. At the same time, the Istanbul draft contained a broad limitation on any military agreements that “would harm the security of other parties [including Russia].” Such wording could foreclose important defense cooperation between Ukraine and its Western partners that is essential for Ukraine’s self-defence and would otherwise be compliant with permanent neutrality.

Permanent neutrality also often places certain limitations on the establishment of military bases and the presence or transit of foreign military personnel on neutral territory during peacetime. However, the exact scope of this limitation is under debate. State practice demonstrates that the temporary presence of foreign troops does not necessarily contradict permanent neutrality when it does not render compliance with the law of neutrality impossible. To comply with the law of neutrality in the event of a relevant armed conflict, foreign troops would need to leave neutral territory as soon as possible. Admittedly, the permanent military bases would make it hard to do this. However, joint military exercises, especially those not simulating a joint war against a particular rival, as well as other forms of temporary military activities, and the presence of foreign military trainers and advisers, would not necessarily contradict permanent neutrality (see the relevant practice of joint military exercises on the territory of permanently neutral Switzerland, Malta, and Cambodia). As another example, Ireland has long permitted the U.S. Air Force to use its Shannon Airport for landing and refueling facilities, arguing that it complied with its policy of neutrality. At the same time, the Istanbul drafts contained sweeping prohibitions on any military activity of foreign states, including temporary ones, on Ukrainian territory. Russia also demanded a veto over joint exercises with foreign states on Ukrainian territory. Such sweeping prohibitions are not necessary elements of permanent neutrality.

Permanent neutrality does not constrain the neutral state’s economic, security, and foreign policy unless the neutrality instrument or related instruments contain relevant requirements voluntarily accepted by the state. Among other things, during peacetime, a permanently neutral state can export weapons and ammunition to countries not engaged in international armed conflicts. For example, Switzerland exported $757 million worth of military equipment to 60 countries in 2024. A neutral state can also do joint arms production with foreign arms manufacturers.

Importantly, the concept of permanent neutrality does not put any limitations on the self-defense and deterrence capabilities of the neutral state. Indeed, in the Nicaragua case, the International Court of Justice found that “[t]here are no rules, other than such rules as may be accepted by the State concerned, by treaty or otherwise, whereby the level of armaments of a sovereign State can be limited.”

Moreover, considering that a neutral state has the duty “to defend its neutrality, if necessary by the use of arms,” some scholars argued that the permanently neutral state is generally obliged to maintain armed neutrality by having the necessary military capabilities to protect itself from armed attacks. Switzerland has been using the concept of robustly armed neutrality for a long time, saying that “greatly limiting its defence possibilities would be a handicap for [the] country and its inhabitants. The purpose of neutrality is to enhance the country’s security, not to restrict its defence capability.” Ukraine’s armed neutrality or nonalignment also has the potential to make it secure if it can get a robust postwar security arrangement.

Security Arrangement to Ensure Secure Neutrality or Nonalignment

One of the key concerns of Ukraine in the current negotiations with Russia is how to ensure the country’s security after the war ends, including deterring any potential Russian attacks in the future. For a long time, the prevalent view has been that only NATO membership can provide a real guarantee of security to Ukraine. However, considering that NATO membership appears unattainable in the short term, and highly uncertain even in the long term, alternative security arrangements need to be explored.

One of the common objections to any considerations of neutrality for Ukraine is that it will make Ukraine defenseless in the face of future Russian aggression, show weakness, and invite further aggression. This line of argumentation often highlights that Ukraine’s non-bloc status in 2014 did not prevent Russia’s unlawful occupation of Crimea in 2014, which prompted the country to abandon the non-bloc status and declare NATO aspirations in the first place. These arguments overlook the fact that Ukraine has never had a truly robust security arrangement that could have meaningfully enhanced the country’s security. As I explained in earlier Lawfare pieces, the Budapest Memorandum’s security commitments from the United Kingdom, the United States, and Russia, which Ukraine received in exchange for relinquishing its right to nuclear weapons, were shallow and insufficient to exert any meaningful deterrent effect on Russia. Also, as of the start of Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014, Ukraine had considerably neglected its armed forces, including due to the fault of its political leadership, which cannot be allowed to happen again.

Ukraine’s potential armed neutrality can enhance Ukraine’s postwar security with the help of two mutually compatible security elements: security guarantees to a neutral Ukraine and Western security obligations to support Ukraine’s defense and deterrence capabilities, including robust armed forces and an indigenous defense industry.

Security Guarantees

Although security guarantees are nowadays associated primarily with collective defense obligations within military alliances, there have been historical precedents of security arrangements involving the use of force to protect permanently neutral states. For example, when the Concert of Europe, consisting of Austria, Prussia, the United Kingdom, France, and Russia, recognized Switzerland’s permanent neutrality in 1815, its Quadruple Alliance conveyed the intention of the parties “to maintain by force if necessary, the general European settlement of which the Swiss settlement was a part.” Also, in the 1830s, the Concert of Europe members placed under their guarantee the treaties establishing permanent neutrality of Belgium and Luxembourg. Germany violated Belgium’s neutrality in 1914, while executing its Schlieffen plan to swiftly invade France via Belgium, calling the neutrality treaty just a “scrap of paper” and committing atrocities in the country. However, the United Kingdom famously entered World War I to protect Belgium’s neutrality in performance of the guarantee. At the same time, it did not react to the German earlier invasion of Luxembourg, interpreting its way out of the neutrality guarantees. The Belgium and Luxembourg stories teach a lesson that any external security guarantees need to be complemented by the neutral state’s robust standing army. As others have put it, “there is nothing guaranteed about security guarantees.”

As explained above, the latest Istanbul draft contemplated a somewhat similar approach of multilateral security guarantees, however, much more concrete than in the Belgian and Luxembourg cases. The critics argue that any bespoke guarantees may not have sufficient credibility to deter aggression, because, unlike NATO, they are not a “known quantity” and would not involve the same level of military resources and signaling. Still, certain factors make them a significant variable in the would-be aggressor calculus. First, their violation would likely create negative effects for the guarantors’ other security guarantees, including those within military alliances. It thus would force the guarantors to think carefully before failing to act on their pledge. The guarantors can amplify this factor by constantly reaffirming that they have an ironclad guarantee to Ukraine’s neutrality. Second, if Russia agrees to Ukraine’s armed neutrality, it might have fewer incentives to attack Ukraine again, as any aggression could lead to Ukraine legitimately abandoning its neutrality status like Belgium and Luxembourg did following World War I. These considerations, on their own, are not enough to make Ukraine feel secure. However, their combination with a robust Ukrainian army and the related binding obligations of Western partners to support it and provide Ukraine with a promise of increased support in case Russia attacks again should be sufficient.

An important consideration is that participation of Russia in Ukraine’s neutrality instrument, including the multilateral guarantees framework, may give it an opportunity to impose its interpretation on and influence parameters of Ukraine’s neutrality, and threaten the use of force (even unlawfully) to enforce its understanding of neutrality. The Soviet Union took a similar approach in respect of Austria with which it concluded the 1955 Moscow Memorandum addressing its planned neutrality. For example, in 1960, Nikita Krushchev stated that the USSR would provide military assistance to Austria if its neutrality was endangered. For similar reasons, Switzerland did not want to get direct security guarantees from the Concert of Europe, fearing that they may imply their right of supervision or even intervention. Also, in a somewhat different context, when the U.S. invaded Cambodia in 1970, the Nixon administration alleged that the country violated its neutral status during the Vietnam War, which is sometimes considered to be the origin of the unwilling and unable doctrine. Although the Istanbul drafts tried to mitigate these risks by conditioning the invocation of security guarantees on Ukraine’s invitation, the preferred option would be to avoid having Russia as a party to the neutrality instrument, potentially getting its acquiescence via the UN Security Council or General Assembly, as I explain below.

As explained above, during the Istanbul talks, the Ukrainians were unable to persuade their Western partners to seriously consider such multilateral security guarantees, even if Russia were to agree to them. However, the current U.S. administration’s approaches might make them feasible for the following reasons. First, the administration has a predisposition to old great power deals like the Concert of Europe made in respect of Switzerland and Belgium. Second, the administration wants to deliver on its promise to end the war quickly and might seriously consider such a neutrality-related security guarantee if it would bring about a settlement. Third, the administration has demonstrated a tendency to engage in high-risk signaling to achieve its objectives in the past.

On a separate note, when Ukraine joins the European Union, it can also benefit from the EU members’ mutual aid and assistance commitments under Article 42(7) of the Treaty on European Union in the event of any armed attacks against it, which would be compatible with its permanent neutrality.

Self-Defense and Deterrence Capabilities

Ukraine’s defense capabilities are the sine qua non element of securing its independence and neutrality. Switzerland’s armed neutrality during the Cold War can serve as one of the useful examples in this respect. Namely, being neutral in the Cold War between two nuclear-armed blocs, Switzerland took a strategy of “preventing involvement in any armed conflict through dissuasive conventional means” by having the ability to defend itself against conventional attacks. Notably, despite being a country of only around 6 million people at the time, Switzerland had a army of around 625,000 in the 1960s, along with top-notch military equipment and civil defense infrastructure. It also freely conducted its foreign and domestic policy without outside interference. Although Switzerland had the benefit of the hard-to-invade mountain terrain, Ukraine has the potential to replicate a similar approach, due its significantly larger population and territory, and make its neutrality work as a “Swiss clock.”

Many experts agree that this approach is feasible, particularly given that Ukraine’s ability to defend itself in the current war serves as proof of concept. For example, Michael E. O’Hanlon and Paul B. Stares described this path as follows:

Ukraine can defend itself effectively if attacked in the aftermath of a cease-fire agreement by creating a multilayered territorial defense system for the roughly 80 percent of its pre-2014 territory that it still controls. This step would comprise a hardened outer defense perimeter, a strategic rapid-response force to respond to serious threats, and enhanced protection for major population centers and critical infrastructure. A defense system configured this way would require a substantial military force—some 550,000 on active duty (drawing on professional and conscripted personnel) and another 450,000 in ready reserve. Given Ukraine’s demographic outlook, creating such a force will be difficult, but not impossible.

According to O’Hanlon and Stares, Ukraine would need to spend between $20 and $40 billion per year, which would require support from its Western partners. Importantly, that is much cheaper than supporting Ukraine during active hostilities or dealing with the Russian threat if it subjugates Ukraine.

As I explained elsewhere, the bilateral security agreements between Ukraine and its Western partners, including the U.S.-Ukraine Security Agreement, can be a significant tool in ensuring that Ukraine has necessary support to maintain its “credible defence and deterrence capabilities,” but they require significant improvements. Among other things, they need to be transformed into legally binding treaties ratified by the partners’ parliaments; include detailed criteria of what Ukraine’s defense and deterrence should look like; and contain exact figures of support akin to the U.S.-Israel MoU (see detailed suggestions in my Lawfare piece). They would also need to be calibrated to Ukraine’s neutral or nonalignment status by excluding incompatible provisions, including ones related to future NATO membership.

Importantly, the mentioned security agreements also include the Western partners’ commitments to provide the necessary military and economic assistance to Ukraine if it comes under attack after the end of this war. That said, the U.S.-Ukraine agreement contains the softest language in this respect, requiring significant improvements (see detailed suggestions in my Lawfare piece). If the security guarantee option is considered, it would be logical to incorporate this provision into it, thereby consolidating in one document both the use of force and military and economic assistance obligations in case of future armed attacks.

Establishing Neutrality or Nonalignment

One of the challenging parts of Ukraine adopting neutrality or nonalignment is that the Ukrainian Constitution mentions Ukraine’s strategic path to NATO and requires the president to be its guarantor. Although amending those provisions does not require a popular referendum, it would require a two-thirds supermajority in the parliament and other stringent procedures, and it can happen only following the end of martial law.

Although some people suggested that having a binding UN Security Council resolution would be sufficient, it is essential to remember that, as a matter of Ukrainian law, the Ukrainian Constitution takes precedence over international law. Also, it is crucial that any settlement is considered legitimate by the Ukrainians, which would, in addition to normative and democratic considerations, make it more durable. Therefore, the best approach would be for Western partners, including the U.S., to propose to the Ukrainians robust security arrangements (as discussed above) that would convince the Ukrainian leadership and population that armed neutrality is safe and viable, thereby making the constitutional amendments feasible.

As an option, for example, the U.S.-Ukraine Security Agreement and security agreements with other willing partners can be amended to include both the robust security obligations to Ukraine and provisions about its armed neutrality or nonalignment. In a similar fashion, permanent neutrality of Malta was established in an agreement with Italy. The UN Security Council or General Assembly can later endorse such agreements if need be. Such a model would not allow Russia to control the exact parameters of Ukraine’s armed neutrality and security cooperation with the West. From an optics perspective, that would also make the arrangements more palatable for the Ukrainians and Europeans by avoiding a joint security guarantee with Russia, while still securing its consent or acquiescence through the United Nations.

Negotiations Considerations

One of the key challenges of the current negotiations is that Russia seems to be determined to stick to its long-term goal of returning Ukraine to its sphere of influence, or what they call “near abroad.” The reasons for this are most likely multi-causal. They include imperial considerations, including Russia’s claims that it has some form of entitlement to Ukraine and that Ukrainians are not a separate nation. At the same time, from the balance of power perspective, Russia also considers a strong Ukraine that has joined the West a strategic disaster in its competition with the latter. The two reasons are not mutually exclusive. Therefore, in any potential discussions about neutrality, it is paramount to diminish Russia’s prospects of subjugating Ukraine down the road by adopting a robust security framework for Ukraine. The question then is, why would Russia agree to neutrality in such a case? This is where the proper combination of sticks and carrots comes into play. Given continuing robust military and economic pressure, Russia might realize that it is better to pocket some strategic benefits of Ukraine’s armed neutrality, including strategic denial of the Ukrainian territory to NATO, than fight many more years and risk getting much less down the road. Indeed, the concept of neutrality has been often used precisely for managing the balance of power between military blocs, and the Soviet Union recognized similar benefits of the strategic denial to NATO during the Cold War. That would also allow Putin to sell the deal to his domestic audience more easily.

As historian Stephen Kotkin put it, “There’s this place in between which is called deterrence plus diplomacy. And deterrence plus diplomacy means, they’re scared of me, but I talk to them. I don’t talk to them just to talk and I don’t scare them just to scare them. I’m not a hawk nor a dove. I’m a combination, I have deterrence and I have diplomacy.” This is good advice for approaching negotiations with Russia at this point.