Must the House Vote to Authorize an Impeachment Inquiry?

Despite what White House Counsel Pat Cipollone and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy have argued, it is constitutionally acceptable for the House to initiate an impeachment without a formal vote.

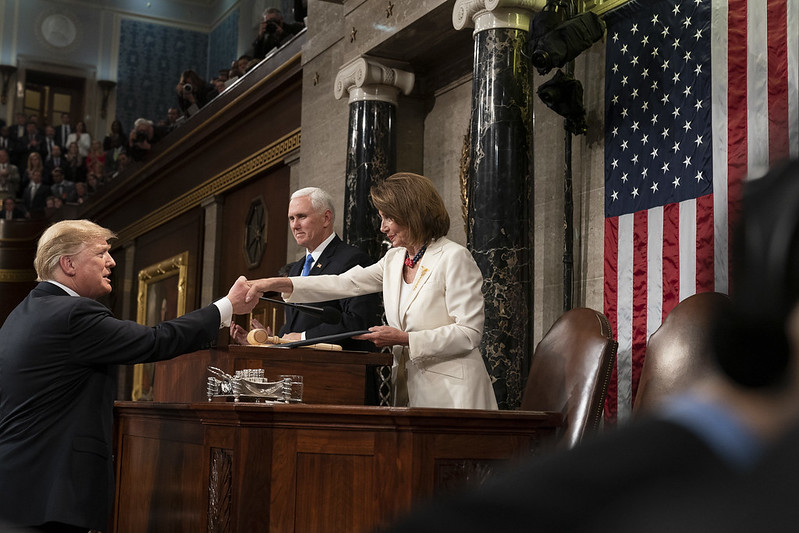

Since taking control of the U.S. House of Representatives in the midterm election of 2018, the Democrats have been exploring how it might be possible to pursue an impeachment inquiry while retaining some plausible deniability about whether they are actually doing so. As President Trump has continued to behave in his usual manner, and as the Democratic caucus has gradually coalesced around the view that an impeachment might be necessary, the process has become more explicit. As the center of gravity in the caucus shifted toward impeachment after the revelation of Trump’s phone call within Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi finally announced that the “House of Representatives is moving forward with an official impeachment inquiry.”

But what counts as an “official impeachment inquiry,” and what is required to move forward with one? House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy sent a letter to Pelosi asking her to “suspend” the impeachment inquiry until “transparent and equitable rules and procedures” could be put in place and a floor vote authorizing an impeachment inquiry could be taken. Pelosi responded that no vote was necessary. Now White House Counsel Pat Cipollone has written to Pelosi informing her that the administration will not cooperate with the House’s “constitutionally invalid” impeachment inquiry, in part because the House had not voted “to authorize such a dramatic constitutional step” or provided the president with “due process protections.”

Is it constitutionally acceptable for the House speaker to initiate an impeachment “by means of nothing more than a press conference”? In short, yes.

The constitutional text on this issue is spare. The Constitution simply says that the House has the sole power of impeachment. Ultimately, if the House wants to impeach someone, it needs to muster a simple majority in support of articles of impeachment that can be presented to the Senate. How the House gets there is entirely up to the chamber itself to determine. There is no constitutional requirement that the House take two successful votes on impeachment, one to authorize some kind of inquiry and one to ratify whatever emerges from that inquiry. An impeachment inquiry is not “invalid” because there has been no vote to formally launch it, and any eventual impeachment would not be “invalid” because the process that led to it did not feature a floor vote authorizing a specific inquiry.

Of course, the House’s own rules might require such a vote, and the House must follow its own rules until it chooses to change them. But there is no rule requiring such an authorizing vote, and neither McCarthy nor Cipollone points to one. The House has changed its internal procedures dramatically over time. At one point, the House did not rely on standing committees but instead created select committees to handle many legislative tasks. Through much of its history, the House has limited the investigatory powers of its standing committees and required that those committees go to the floor to receive special authorization to issue subpoenas or spend substantial resources on staff. It no longer does so, and so it no longer needs to take such votes to specially authorize particular investigations. The House might want a select committee to pursue an impeachment inquiry, but it could also choose to rely on its standing committees to do the job with their preexisting jurisdiction and resources—and that is how the Democratic leadership has decided to approach the current impeachment inquiry. It is not up to the target of an impeachment to determine who will compose the committee that will draft the articles of impeachment or who will chair that committee.

It is not hard to imagine circumstances in which no formal impeachment inquiry is even necessary. The House might simply move directly to a vote on proposed articles of impeachment without having ever authorized an inquiry, let alone provided some kind of formalized opportunity for the target of the impeachment to respond. Before the Democrats took control of the House after the 2018 elections, this model had already been tried out. Democratic Rep. Al Green has introduced directly onto the House floor three different resolutions of impeachment against the president, in 2017, 2018 and 2019. The core of those articles of impeachment focused on the president’s public statements and how they had brought the office of the presidency into “contempt, ridicule, disgrace, and disrepute” and “sown seeds of discord among the people of the United States.” There was no serious need for the House to inquire into whether the president made the statements that formed the factual basis of those articles of impeachment. The open question was simply whether the president’s rhetoric amounted to impeachable offenses, and no formal inquiry was necessary for the members of the House to reach a conclusion on that issue (though perhaps hearings would have been useful for helping the House deliberate on that question).

In the case of Green’s resolutions, there was nothing like a majority ready to pursue an impeachment, and so the House quickly agreed to table the motions. Green was using the resolutions to try to build political support for general opposition to the president. But it is not hard to imagine circumstances in which a similar resolution was not just an attention-grabbing move but actually had the support of a House majority. Where Green’s particular resolutions were quickly set aside, some similar measure might instead be adopted by a simple floor vote. A majority of the House could reasonably conclude that they knew all they needed to know to impeach an officer without any formal inquiry of their own and simply on the basis of press clippings, personal observation, a special counsel report, or a criminal trial record. The House does not constitutionally need to authorize an impeachment inquiry because it does not constitutionally even need to have an impeachment inquiry.

Cipollone’s letter suggests that only an authorization vote would make the House “democratically accountable” for its actions. But it is not obvious why that should be. To actually impeach an officer, the House members do have to record a vote and be individually accountable for whether or not they took that step. Why should they have to separately go on record merely to authorize an inquiry? If the inquiry results in an impeachment vote, there will be a record of each member’s position. If the inquiry does not turn up sufficiently serious impeachable offenses, then the process dies. Arguably it was once the case that the House believed that members should go on record authorizing particular investigations, but it is not clear that those votes were ever about holding the members democratically accountable to their constituents (as opposed to holding committees accountable to the floor). In any case, the House does not now expect that each member must go on record before a committee launches an investigation, for example, into what happened in Benghazi or how the president might be profiting from foreign guests in his hotels. As a practical matter, the voters increasingly cast partisan votes for House members and are perfectly capable of holding them accountable for how the House majority spends its time, whether or not an individual member ever goes on record authorizing particular investigations.

But does the House need to hear from the target of an impeachment before deciding whether to impeach? McCarthy and Cipollone assert that the subject of impeachment should be able to present evidence to the House, object to the admittance of evidence, and cross-examine and recommend witnesses. They want something like a trial before an impeachment vote. Of course, the Constitution specifies that an impeached officer is entitled to a trial—in the Senate after a successful impeachment vote. The Constitution imposes no such procedural burdens or fact-finding requirements on the House, and it does not guarantee a federal officer the right to such procedures before being impeached.

Cipollone accuses the Democratic majority in the House of seeking to “overturn” the presidential election through a “highly partisan and unconstitutional effort,” but the House Democrats cannot “overturn the popular will of the voters,” as House Judiciary Chair Jerrold Nadler put it back when a president of his party was threatened with impeachment. Impeachment is the beginning of a constitutional process, not the end. If a democratically elected president is to be displaced from office, it will only be as a result of a bipartisan supermajority of senators voting to do so after a trial. If the House could by itself and by majority vote oust a president, then there would be good reason to demand a robust process before reaching that decision. If the Democrats held it within their power to remove a sitting president, then there would be good reason to object to a partisan process that did not give a fair hearing to the other side. But as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has been sure to point out, the Democrats do not have it within their power to remove the people’s choice of a president without Republican cooperation.

Impeachment has frequently been analogized to a grand jury indictment, and the analogy is informative here. The House is a prosecutorial body in an impeachment context. The House members themselves must decide what steps they think are necessary to satisfy themselves that a particular impeachment is warranted and to prepare a credible case that can be argued in the Senate, where the defense will have an opportunity to poke holes in it. It might be prudent for the House to create a more robust adversarial proceeding in order to help the House members themselves assess the strength of the case, but any such process is for the benefit of informing the House, not protecting the accused from a possible impeachment. A federal officer has no particular right not to be impeached, and the bar for impeachment is consequently set low.

The Senate trial, by contrast, provides an opportunity for an accused officer to mount a robust defense, plead his or her case, and seek total vindication. The procedural bar for a Senate conviction is set high. There, the House can have no expectation of a sympathetic hearing and the defendant can make use of the fact that a bipartisan supermajority in the upper chamber will almost always be necessary to remove him or her from office. It might not be possible to impeach a ham sandwich in the House, but the accused has no expectation of a fair or bipartisan hearing in the lower chamber.

Politically, the Democratic leadership is avoiding a vote to authorize an impeachment inquiry because thus far they seem uncertain whether they could win such a vote. If a vote authorizing an impeachment is seen by some citizens as indistinguishable from a vote to impeach, then House members in purple districts might well prefer to know how strong the case for impeachment actually is before they have to go on record effectively supporting an impeachment. In a perfect world, voters would be able to distinguish support for an impeachment inquiry from support for an impeachment—but in our imperfect world, the House leadership is expected to protect caucus members from unnecessary politically damaging votes. As a matter of institutional design, Congress’s ability to inquire into misconduct should not be held hostage by such electoral calculations. Rather, the system should allow for a process that allows the investigation of allegations of misconduct and uncovering of the facts, and that forces politicians to take responsibility for how they respond to those facts. A system that instead puts a thumb on the scale on the side of hiding potential misconduct is hardly in the public interest, even if it might serve the immediate personal or partisan interests of those who fear that their conduct might come under scrutiny. Americans should be reluctant to build into constitutional practice such a bias toward obstructing investigations. The constitutional framers did not themselves build in that kind of bias.

The House is a partisan political institution. It is inescapable that impeachments, which require only a simple majority vote, will sometimes be partisan in nature. A House majority must anticipate what will happen in a Senate trial if it proceeds to an impeachment on a largely partisan basis; House members must anticipate how their own constituents will react if they cast a vote for an impeachment along largely partisan lines; and the House must consider what the consequences are for the nation if a high constitutional officer such as a president is impeached along those partisan lines. Such considerations might encourage the House not to act if it cannot act on a bipartisan basis, and Pelosi has often emphasized that consideration. But if a majority of the House becomes convinced that an impeachment is necessary and useful, even if it can attract few members of the other party to its cause, voters will have the option of considering this when they next cast their ballots for their representatives.

Ultimately, this is where the Republican position has some traction: on the political question of how the public will evaluate the impeachment process. The White House can make its case to the voters that the House should make use of a more elaborate process before voting on a presidential impeachment, or that the Democrats have pursued impeachment with unseemly zeal, or that an impeachment is not substantively justified and that the Democrats are grasping at straws. Those are political arguments that the voters can and should hear and that the electorate can and should and undoubtedly will judge in 2020. Perhaps the Democrats can blunt some of those objections while still accomplishing their own goals with an impeachment inquiry—but that is a political question, not a constitutional one.

-final.png?sfvrsn=b70826ae_3)