The Situation: Grand Juries in Savage Times

The Situation on Sunday looked out the window of a chic cafe to survey the wreckage of war.

Yesterday, the New York Times reported that a federal grand jury in Washington had declined an indictment against six members of Congress who had released a video to remind active duty military personnel that they did not have to follow unlawful orders. “It was remarkable,” The Times reported,

that the U.S. attorney’s office in Washington—led by Jeanine Pirro, a longtime ally of Mr. Trump’s—authorized prosecutors to go into a grand jury and ask for an indictment of the six members of Congress, all of whom had served in the military or the nation’s spy agencies.

But it was even more remarkable that a group of ordinary citizens sitting on the grand jury in Federal District Court in Washington forcefully rejected Mr. Trump’s bid to label their expression of dissent as a criminal act warranting prosecution.

Remarkable in the sense of being worthy of remark? Yes, absolutely.

Remarkable in the sense of being surprising? Surely not.

The Justice Department has authorized prosecutors to go after any number of political opponents of the president on the most specious of grounds. Indeed, it has often ordered prosecutors, against their will, to work these cases—prompting conscientious objection and resignation and sometimes firings. That the Justice Department would attempt to criminalize the pure speech of six opposition members of Congress, all of them veterans of either the military or the intelligence community, is the least surprising thing in the world. It is just a part of the new abnormal.

Nor is it surprising that a grand jury balked. Grand juries have been balking a lot these days. Some of these cases are high profile—like the effort to indict “sandwich guy,” for example, or the serial efforts to prosecute New York Attorney General Letitia James. It’s impossible to know how many grand juries have rejected how many cases, but it’s clearly happening quite a bit. As Josh Gerstein writes in Politico:

Grand juries in Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Alexandria and Norfolk, Virginia, have all rebuffed federal prosecutors recently.

Those rejections have derailed or impeded prosecutions of former FBI Director James Comey, New York Attorney General Letitia James, people accused of threatening Trump, and little-known activists accused of clashing on the streets with federal officials..

. . .

The top federal prosecutor in Los Angeles, Bill Essayli, has also reportedly been exasperated by grand juries refusing to issue indictments in cases stemming from Trump’s immigration crackdown in southern California. At one point earlier this year, Essayli’s office had managed to secure indictments in less than a quarter of the felony cases it brought in connection with protests or immigration raids, the Los Angeles Times reported.

The idea of punishing members of Congress—or anyone—for speaking in public the self-evident truth that servicemembers have a duty to defy unlawful orders is a democratic monstrosity. It is monstrous to attack the retirement rank of a senator on such basis, as the administration has done with Sen. Mark Kelly, and it is even more monstrous to deploy the criminal process for such a purpose.

When the government engages in monstrosities, we see, in response, that layers of the democratic substrata that normally lie invisible suddenly become visible. The grand jury seems like a formality to many people in normal times. Grand juries never reject cases, after all. They are instruments of the prosecution, we all learn cynically, that offer no real civil liberties protection. Queue inevitable ham sandwich line.

Until, that is, the government engages in the monstrosity of attempting to prosecute sitting members of Congress for speaking the truth about servicemembers’ obligations to the law. Or until the government tries to prosecute protesters, say, who get roughed up my federal agents for roughing up federal agents. Or until the government tries to prosecute political enemies who once investigated or cases against President Trump.

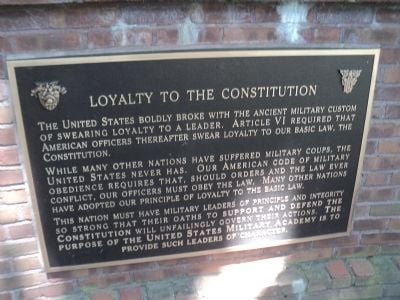

Then, all of a sudden, the substrate layer of civil liberties gets exposed. And it turns out that having 23 people vote on whether the government even has probable cause that a given person committed a crime using non-admissible evidence is a genuinely important civil liberties protection. No, it’s not one we need often in civilized times. But the Constitution has to govern us in savage times too. And when you have a president who wants to prosecute legislators with the temerity to remind service-personnel of their duty to obey the law, situating 23 citizens between him and the power to haul them into court turns out to matter.

There are other provisions of the Constitution like this too. The Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against “cruel and unusual punishment,” which at its core protects against the particularly tortuous deaths inflicted in Stewart England—drawing and quartering and the like—doesn’t seem to have a lot of application these days, though the Supreme Court has widened the scope of its coverage over the years. But I, for one, am glad it’s there, however much work it may not do in preventing abuses by ICE in detention facilities and lots of other things. Because society does regress and it sometimes does regress to points where you need protections against barbarities we haven’t had cause to think about in a few centuries. And it is useful in such savage times to have a floor of civilization below which we will not sink—lo though we may try. Who knows? Maybe we will even see Third Amendment litigation sometimes soon.

The Situation requires us all to think about what power we have and how we can use it. That means something different for members of Congress with military and intelligence backgrounds who can speak to the public loudly than it does for protestors, who may not have loud individual voices but who can aggregate their voices.

It means something different for public servants than for journalists.

It means something different for citizens than for people who have to fear ICE, either because they are not in the country legally or because they might get rounded up and deported even though they are here legally.

And it also means something different for people who happen to be put on grand juries—or petit juries—than it does for the rest of us.

The Constitution entrusts these people with the democratically sacred duty: The government cannot punish a person without first convincing grand jurors of something—without, in other words, getting popular permission. In savage times, that permission is no mere formality. It is the line between a society that flirts with barbarism and a society that plunges into it.

The Situation continues tomorrow.