Why Trump’s Madman Act Doesn’t Work

Editor’s Note: One way to explain President Trump’s bargaining style is that he is being deliberately irrational, raising the stakes by threatening to be a “madman” in order to extract more concessions. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Caitlin Talmadge and Oxford University’s Samuel Seitz dissect the madman theory, explaining why it failed in the past and is unlikely to produce successes in the future.

Daniel Byman

***

If you’re having trouble keeping up with the zigs and zags of President Trump’s trade policies, you’re not alone. American trade policy has swung wildly over the past several months, with tariffs being paused and then reimposed. Certain countries have faced particular volatility. For example, in early October, Trump said that the sticking point in trade talks with Canada was that he wanted to “be a great man” like Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, although Trump indicated that a mutually beneficial trade deal was achievable given the “mutual love” between the United States and Canada. More recently, though, Trump further hiked tariff rates on America’s northern neighbor in response to a pro-free trade advertising campaign funded by Ontario, and he is now refusing to even meet with Carney.

These erratic escalations in Trump’s trade war may be deliberate. As Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent explained shortly after “Liberation Day” back in April, “In game theory, it’s called strategic uncertainty, so you’re not going to tell the person on the other side of the negotiation where you’re going to end up.” While Bessent and Trump might label this strategy strategic uncertainty, a previous resident of the White House, Richard Nixon, called it the “madman theory” of diplomacy, and it is an approach that has been tried—mostly unsuccessfully—by leaders as diverse as Nikita Krushchev and Moammar Gadhafi.

Traditionally, leaders seek bargaining advantages by entering negotiations from a position of strength. Being stronger means they can impose more costs on the opponent than the opponent can on them, granting them leverage. To draw an analogy from outside international politics, consider the game of chicken, where two cars race toward each other until one driver swerves, becoming the chicken. In this competition, the driver in the larger car enjoys an advantage because, by virtue of operating a more robust vehicle, she can inflict far more damage on the other car than it can on hers. The result is that her opponent experiences greater pressure to avoid a crash.

Of course, for this logic to work, both sides must care about costs. It is this assumption that madman theory seeks to challenge. A madman, after all, is mad. He does not care about costs either because he subscribes to an extreme set of ideological views that weigh costs differently than most or because he is simply irrational and thus incapable of cost-benefit analysis.

In any event, the threat of suffering costs as a result of his actions does not restrain him. Thus, the theory goes, he has an important advantage in negotiating, and the other side, which is sensitive to costs, is compelled to make concessions rather than risk further escalation. To return to the previous example, if the driver of the smaller car is drunk and thus incapable of rationally weighing risks, he may not recognize his opponent’s strength and plow on regardless, perhaps even accelerating! By discounting his own safety, the operator of the smaller car can take actions that impose grievous harm on the other driver, even if he comes off relatively worse, and thus force his opponent to chicken out and swerve. According to madman theory, it is this asymmetric recklessness that grants the small car leverage.

So how well does this theory hold up in practice? In 2020, we wrote an article that assessed the logic and evidence behind madman theory. What we found should give pause to Trump or any other leader seeking to use this approach. Specifically, we identified three recurring issues that confront leaders attempting to successfully execute a madman strategy.

First, madman strategies face serious credibility problems because it is difficult for leaders to persuade anyone that they are truly mad. Reputations tend to be established early in a leader’s tenure, and so unless a leader is consistent in acting erratically and with complete disregard for costs, it is unlikely that foreign observers will find the act believable. For example, while then-Vice President Nixon was impressed by Khrushchev’s blustering over the Berlin crisis of the late 1950s, Nixon ultimately (and correctly) deemed the Soviet leader’s threats to risk nuclear war over the city a bluff—and the United States remained in West Berlin for the rest of the Cold War.

Second, madman tactics suffer from communication problems. Unsurprisingly, behaving erratically can create doubts about one’s intentions and demands. In 1969, for example, President Nixon himself attempted to execute a madman strategy. In a bid to end the Vietnam War, he decided to act as if he had reached such a point of desperation that he was willing to threaten a nuclear war with North Vietnam’s patron, the Soviet Union. To help legitimize this threat, he raised the alert level of certain nuclear forces. The hope was that the Soviets would detect this change in U.S. posture, become frightened, and push their North Vietnamese allies to negotiate. But while Moscow did eventually detect Nixon’s antics, it could not discern the message they were intended to convey. In fact, there is some evidence the Soviets thought the U.S. signal was meant to pressure them to back off of an unrelated border war with China. Needless to say, Nixon’s nuclear alert did not lead to an end to the Vietnam War on America’s terms.

Finally, madman behavior creates a reassurance problem. If a leader is consistently inconsistent, erratically changing tactics and reneging to squeeze out further concessions, negotiating partners have no incentive to concede. Indeed, they have strong reasons to stand firm. Successful negotiations require that both sides stick to their word. After all, as Reid Pauly notes, if a police officer says, “Stop or I’ll shoot,” you had better stop. But if she says, “Stop, though I may decide to shoot anyway,” you should probably be less inclined to obey.

Unfortunately for the Trump administration, these challenges are all likely to plague its approach to trade negotiations. For one, while Trump is more willing to run economic risks with tariffs than previous U.S. leaders, he is still clearly sensitive to costs. In the wake of April’s market downturn, he backed off the more extreme tariff policies. More recently, he publicly acknowledged that continuing the trade war with China at current levels was simply unsustainable.

As a result of this behavior, Trump is developing the reputation not of a madman but of a reckless yet still cost-sensitive president. Indeed, some observers on Wall Street allegedly refer to his behavior as TACO, which stands for “Trump Always Chickens Out,” hardly a moniker one wants when entering high-stakes negotiations.

Trump’s tactics also suffer from imprecise aims. Take Canada. Trump has variously justified his trade actions against America’s northern neighbor by citing low Canadian defense spending, insufficient enforcement against fentanyl smugglers, and unfair trading practices. Even if Ottawa wanted to concede, it is very difficult for Canadian policymakers to discern where they are meant to be making concessions. This is especially true in light of the reassurance problem. Canadian officials might agree to spend more on defense, for example, but how can they be sure that Trump won’t just invent a new reason to go after them? Canadians have more reason to worry than most, as Trump has already reneged on trade agreements with them. After all, it was in Trump’s first term that American officials demanded that the NAFTA trade agreement be renegotiated. Canada obliged, but now Trump has reopened the issue even though the current agreement governing U.S.-Canada trade relations, the USMCA, was negotiated by Trump himself!

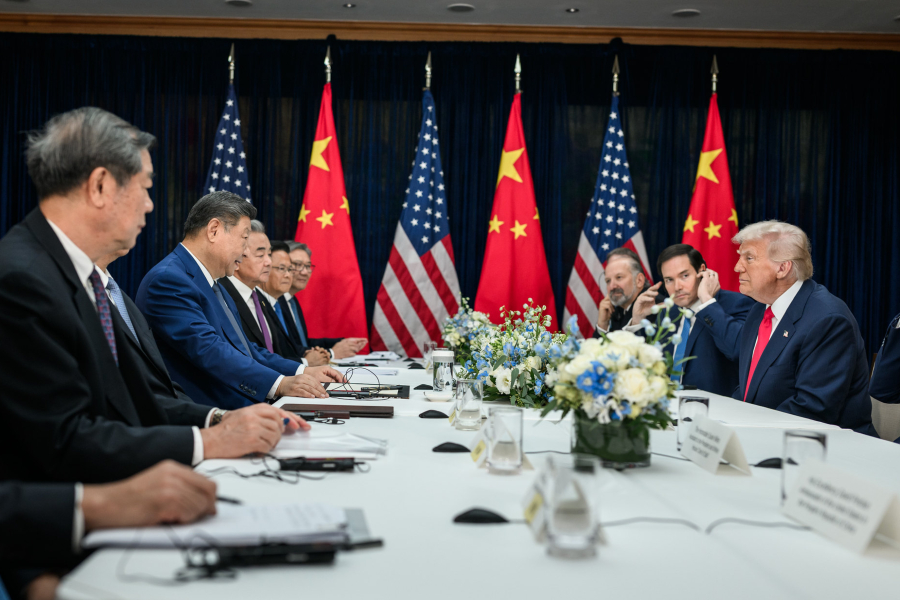

It is certainly possible that Trump will successfully extract some concessions from negotiating partners. Indeed, he already has from the U.K. But these successes are largely a function of America’s traditional sources of bargaining power—namely, the country’s relative economic strength—and not its president’s erratic approach to negotiations. Against more formidable negotiating partners such as China or the European Union, both in trade and in other areas of international politics, unpredictability is a predictably poor tactic for achieving success.

-2.jpg?sfvrsn=f979c73d_6)

.jpg?sfvrsn=407c2736_6)