The Troubling Defense of the Second Strike

Even absent an order to “kill everybody,” the Trump administration’s actions—like its broader military campaign—raise serious legal concerns that demand further scrutiny.

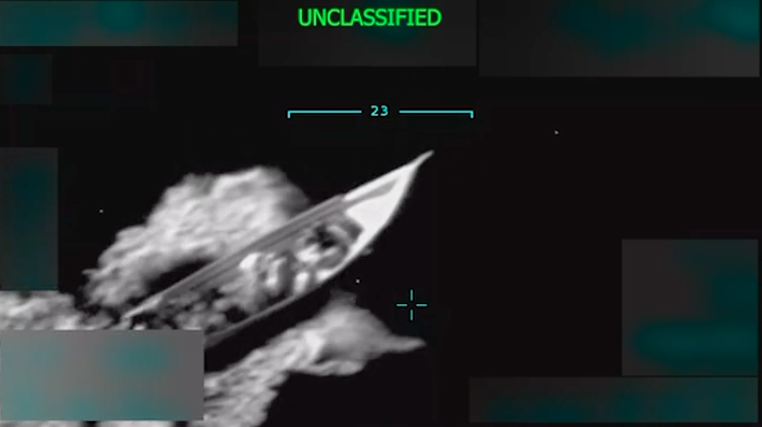

For the past week, much of Washington has been in an uproar over a Washington Post report that Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth issued a verbal order to “kill everybody” prior to a Sept. 2 missile attack on a ship allegedly engaged in narcotics trafficking, which led military commanders to pursue a second strike that killed two survivors who had been “clinging to the smoldering wreck” of their ship. Subsequent reports and statements by senior administration officials have offered competing accounts of Hegseth’s role but otherwise conceded the basic facts. Hegseth and the White House have in turn sought to shift blame to Adm. Frank “Mitch” Bradley, the then-lead military commander for the strikes and current head of Special Operations Command (SOCOM), by making clear that the second strike was his decision.

This past Thursday, Dec. 4, Bradley and Gen. Dan Caine, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, offered the clearest account of the second strike to date in closed-door congressional hearings to representatives from relevant congressional committees. They reportedly testified that Hegseth never gave an order to kill everyone as the Post and others reported. Instead, Bradley said that he ordered the second strike about 41 minutes following the first strike, after he and other U.S. military personnel observed the two survivors—who did not appear to have communications equipment and appeared to signal at the U.S. aircraft monitoring them—trying to rightsize the still-floating portion of their destroyed ship on which they had been floating. In justifying his decision, Bradley explained that he ordered the second strike “to destroy the remains of the vessel…on the grounds that it appeared that part of the vessel remained afloat [and] still held cocaine,” and that “[t]he survivors could hypothetically have floated to safety, been rescued, and carried on with trafficking the drugs[.]”

Prior to this testimony, the bipartisan leaders of the House and Senate armed services committees had publicly committed to engage in “vigorous oversight” and “gather a full accounting” of the decision to pursue a second strike. But it’s not yet clear how much further this oversight will go. At least one Republican member of the Senate armed services committee found the testimony fully vindicating, leading him to describe the second strike as “lawful and needful and… exactly what we would expect our military commanders to do” in such circumstances. Others, however, were less convinced, with at least one Democratic legislator describing the video footage shared during the hearings as “one of the most troubling things I’ve seen in my time in public service.”

In our view, Congress must continue its inquiry. Separate and apart from whatever order Hegseth might have given, the decision to pursue the second strike presents profound questions about compliance with the international law of armed conflict and contradicts longstanding Defense Department guidance. Perhaps more importantly, it may also be a symptom of more fundamental problems with how the Trump administration’s legal justification for its military campaign is shaping operational considerations. If so, it is unlikely to be the last.

The Trump Administration’s Flawed Legal Justification

The second strike on Sept. 2 has raised bipartisan concerns in a way that stands out from the substantial controversy already surrounding the Trump administration’s broader military campaign. To understand why, however, one must first understand the flawed international legal justification the Trump administration has put forward for that campaign—and how the two are inextricably intertwined.

Ironically, the strikes on Sept. 2 were the first in what has since become an extended military campaign. Over the past three months, the Trump administration has pursued 22 strikes against ships alleged to be operated by narco-traffickers in international waters in the southern Caribbean and eastern Pacific, killing at least 87 people. The most recent such strike occurred on Dec. 4, the same day that Bradley and Caine testified before Congress. While the Sept. 2 strikes purported to target members of Tren de Aragua (TdA), the transnational criminal gang whom the Trump administration has painted as agents of Venezuela’s Maduro regime, other strikes have targeted other unspecified groups. To date, the Trump administration has not produced a public list of the groups that are within the scope of the military campaign. Nor has it offered a detailed public international legal justification for its actions, leaving it somewhat unclear exactly how the strikes purport to comply with applicable international law, as the Trump administration has insisted they do.

The Trump administration has, however, offered high-level explanations to members of Congress and the United Nations. According to the New York Times, a notice provided to Congress in October sketches out the purported international legal basis for the administration’s actions:

Specifically, it says that Mr. Trump has “determined” that cartels engaged in smuggling drugs are “nonstate armed groups” whose actions “constitute an armed attack against the United States.” And it cites a term from international law — a “noninternational armed conflict” — that refers to a war with a nonstate actor.

“Based upon the cumulative effects of these hostile acts against the citizens and interests of the United States and friendly foreign nations, the president determined that the United States is in a noninternational armed conflict with these designated terrorist organizations,” the notice said.

The administration reiterated more or less the same justification in later remarks to the UN Security Council, while adding that the United States was using force “in self-defense and defense of others… pursuant to the law of armed conflict and consistent with Article 51 of the UN Charter.” This article in turn states that nothing in the UN Charter is intended to impair “the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations,” suggesting this was the international legal basis for the administration’s actions.

This invocation of Article 51 is not itself exceptional, as individual or collective self-defense have been central to the international legal justification for most U.S. military operations in the postwar era. What is exceptional, however, is what the Trump administration appears to consider “hostile acts” rising to the level of an “armed attack” warranting acts of self-defense. Even the most detailed accounts of the ways in which TdA—which, because it was the stated target of the Sept. 2 strikes, this article focuses on—threatens the United States describe it as engaging in what would generally be considered violent criminal activities, not the sort of targeted and intentional armed hostilities that the United States has relied on to justify military action against al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups. Nor has the Trump administration identified any other state with which TdA has engaged in such hostilities—if there are any—as having requested that the United States act in collective self-defense on its behalf. Instead, the Trump administration appears to be treating narcotics smuggling itself as tantamount to an armed attack, either alone or in tandem with these organizations’ other activities. This aligns with legal positions it has taken in other contexts, where it has accused TdA of “us[ing] drug trafficking as a weapon.”

As one of us explained at length in the days immediately following the Sept. 2 strike, this argument is a severe departure from both conventional understandings of international law and the past official positions of the United States. Most states view the “inherent right of individual or collective self-defence” described in Article 51 as applying where there has been (or imminently will be) armed violence whose “scale and effects” rise to a level of severity above “mere frontier incidents” and other minor hostile encounters. The United States has long rejected this view and asserted that any level of armed violence can constitute an armed attack triggering the right of self-defense. But it has still maintained that an armed attack must entail some degree of “direct physical injury and property damage… like that which would be considered a use of force if produced by kinetic weapons.” This is in part because other states have occasionally accused various non-military U.S. actions—such as the imposition of economic sanctions—as being tantamount to an armed attack, a view to which the United States has traditionally objected. It also reflects the well-established understanding of the authors of the UN Charter and decades of state practice that both preceded and followed it.

According to some reports, the classified Office of Legal Counsel opinion being used to justify the maritime strikes draws parallels between narcotics like fentanyl and chemical weapons. This is most likely an effort to try and bring the administration’s legal theory into closer alignment with these existing U.S. legal positions, specifically by emphasizing similarities in the two chemicals’ physical effects. But even if one accepts this parallel, countless other distinctions make it extraordinarily difficult to square treating narcotics smuggling as an armed attack with even the relatively permissive understandings of international law employed by the United States. After all, most Americans are willing recipients (addiction notwithstanding) of the narcotics purportedly being used to attack them—and smugglers do not necessarily intend for the narcotics to kill the recipients (though they may accept this as a possibility), as this would eliminate their consumers.

Adopting the Trump administration’s definition of armed attack would dramatically expand what kinds of actions may be lawfully answered with the use of military force, with far-reaching and potentially destabilizing consequences. For example, could selling tobacco—of which the United States is the world’s third largest exporter—constitute an armed attack allowing for an armed response? Or economic sanctions and other measures that might restrict access to food and medicine, resulting in similar physical effects? The end result of such broadening is likely to be a dramatic expansion of the circumstances in which states are entitled to resort to the use of military force, in direct tension with what most see as the UN Charter’s intent.

Similar questions pervade President Trump’s determination that the United States is in a non-international armed conflict” (or NIAC) with TdA and similar groups, which suggests that the international lawfulness of U.S. actions should be assessed under the jus in bello rules governing the conduct of hostilities. The conventional international law standard for when a NIAC exists is “[p]rotracted armed violence between governmental authorities and organized armed groups.” Existing Defense Department guidance similarly identifies “the intensity of the conflict and the organization of the parties” as criteria used to distinguish NIACs from “internal disturbances and tensions, such as riots, isolated and sporadic acts of violence, and other acts of a similar nature” that do not trigger the application of the international law of armed conflict.

Neither component of these standards existed for the Sept. 2 strike. It’s not clear what TdA has done that might constitute “protracted armed violence” with the United States (or with any other state that has requested the United States act in its collective self-defense)—except, perhaps, if one accepts the Trump administration’s unorthodox view that narcotics smuggling is itself a form of “armed violence.” Nor is it clear whether TdA constitutes an “organized armed group” of the sort usually required to be involved in a NIAC. The Trump administration’s own intelligence community reportedly assessed that TdA itself was too decentralized to have a coherent organization or command structure, two of the main considerations in weighing whether a group has the capacity to be considered to be in a NIAC.

Separately, the Trump administration has also routinely referred to the targeted groups as “designated terrorist organizations” and described the individuals targeted as “unlawful enemy combatants,” both terms that deliberately echo post-9/11 legal arguments related to U.S. counterterrorism operations. But here, the use of these terms seems intended to obfuscate the legal basis for the Trump administration’s actions more than clarify it. While the Trump administration has designated TdA and certain other cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) and Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs), these determinations only relate to the imposition of financial sanctions and similar measures. They have no bearing whatsoever on the legal authority to use military force, whether under domestic or international law. As for the use of “unlawful enemy combatants,” it’s a label that was routinely applied to members of terrorist groups to suggest they were entitled to a more limited set of protections under international law, in ways that have since been substantially debunked and constrained. Simply put, labeling a group or individual as “terrorist” does not itself help justify the use of force against it under domestic or international law. In repeatedly invoking this framing, the Trump administration is trying to make its actions look more like the sorts of U.S. counterterrorism operations that have come to be widely accepted as legitimate (at least in the United States) since the 9/11 attacks. But in reality, they are something entirely different.

Innovation is an aspect of international legal practice, and states (including the United States) do sometimes advance and rely on novel understandings of international law. But for such interpretations to successfully justify state actions, officials need to try to persuade other states and the broader public that these positions are plausible (or at least that they should not be rejected outright), including by explaining their legal reasoning, addressing critics’ concerns, reconciling their position with state practice and opinio juris, and making the case that it will not destabilize other parts of the international legal system. Yet the Trump administration has made no such efforts. Nor is it clear that such efforts would be likely to succeed.

For these reasons, few countries are likely to accept the Trump administration’s extremely unorthodox view of narcotics smuggling as being tantamount to armed violence of the sort usually associated with armed conflicts, even if they label the smugglers as terrorists or unlawful combatants. As a result, countries are unlikely to view the U.S. strikes as legitimate military activities, even if they were to comply with the jus in bello. Instead, they are more likely to see all 22 (and counting) U.S. strikes—including but not limited to the second Sept. 2 strike—as something else entirely: state-sponsored murder in violation of international human rights law, or perhaps even crimes against humanity, that run counter to some of the most foundational rules of the international system. Under either framework, compliance with the jus in bello and other aspects of the international law of armed conflict is irrelevant as the strikes are already almost certain to be unlawful.

Problems, Even on the Trump Administration’s Own Terms

The second strike on Sept. 2, however, presents a level of legal challenge that goes a step beyond the Trump administration’s broader military campaign. Even if one accepts the Trump administration’s flawed international legal justification at face value, there are good reasons to think that the alleged order to “kill them all” and the resulting second strike were unlawful. No doubt this is part of why the Washington Post’s story raised so much alarm. And while Thursday’s testimony may have alleviated some points of concern, others remain outstanding.

If Hegseth did in fact give an order to “kill them all” as originally reported, then this would be not only a violation of the international law of armed conflict, but a clear violation of longstanding Defense Department policies. The Law of War Manual that stakes out the Defense Department’s official understanding of the international law of armed conflict is unequivocal that “[i]t is forbidden to declare that no quarter will be given” and “prohibited to conduct hostilities on the basis that there shall be no survivors,” including in a NIAC. Admitting to having given such an order would be the equivalent of confessing to a serious violation of the international laws of armed conflict, even under the Trump administration’s own legal framework.

Yet if Bradley and Caine testified truthfully that Hegseth did not give such an order, this alone would not render the rest of the decisions on Sept. 2 lawful or “righteous,” as Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) described them. Other decisions made that day raise equally serious legal concerns, even within the Trump administration’s own legal framing.

The international law of armed conflict prohibits the use of military force against enemy combatants placed hors de combat (or “out of combat”), including individuals who are rendered defenseless by virtue of being wounded or shipwrecked. This obligation is expressly included in Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions, which—per the Supreme Court—applies in the context of a NIAC like the one that the Trump administration claims to be pursuing. The U.S. military is intimately familiar with this requirement, which is reiterated in great detail in both the Law of War Manual and the Operational Law Handbook used to provide more concrete guidance to wartime commanders. (The former defines “shipwrecked” to mean persons “in distress at sea or stranded on the coast who are also helpless,” meaning it would clearly apply to the two survivors.) There are also reports that the two survivors waved at a monitoring U.S. aircraft in the 41 minutes between the two strikes, which some viewers interpreted as an attempt to surrender. Per the Law of War Manual, surrender can provide separate grounds for considering an individual to be hors de combat, if their surrender is genuine, clear, unconditional, and in circumstances where acceptance is feasible.

There are, however, circumstances in which the protections provided to those places hors de combat do not fully prohibit the use of lethal force. Bradley’s reported arguments as to why the survivors could still be targeted—that they tried to “flip a boat ‘loaded with drugs bound for the United States’” and that they “could theoretically call other traffickers to retrieve them and their cargo”—appear to lean on two of these exceptions. Both, however, present serious problems.

First, individuals who would otherwise be hors de combat can lose their protected status if they engage in “hostile acts” or “continue to fight.” So, for example, a grievously wounded individual who nonetheless picks up a rifle and aims at enemy forces may still be legitimately targeted. Yet neither of the Sept. 2 survivors are alleged to have done anything like this. Instead, the triggering event for the second strike appears to have been their effort to right a floating portion of the ship, which may have still had narcotics onboard.

The only way this might be considered a “hostile act” is if one accepts the Trump administration’s framing that smuggling drugs is itself tantamount to an armed attack. Even then, however, this exception could only apply if there was reason to believe that the Sept. 2 survivors were somehow willing and able to continue to engage in the “hostile act” of smuggling those drugs into the United States. Numerous facts reported in the media—that the ship had changed trajectory away from the United States even before the first strike; that the ship had been blown in two and was presumably not operational; that the survivors are not believed to have had access to any radio or communications equipment—cast the factual basis for any such conclusion into serious doubt. While it is true that the two survivors may “hypothetically have floated to safety, been rescued, and carried on with trafficking the drugs” as Bradley reportedly suggested in his testimony, the same would be true of nearly all shipwrecked and wounded combatants, who might theoretically be rescued by their compatriots and ultimately return to the fight. If applied on the basis of this logic alone, the exception for hostile acts would swallow the broader rule protecting those placed hors de combat altogether.

Second, individuals who are hors de combat may still be collateral damage in attacks on lawful military targets, in the same manner as civilians and other protected persons and objects. Some statements by Bradley and others suggest that the target of the Sept. 2 strikes—as well as other strikes in the broader campaign—may be the drugs themselves, not the individuals onboard the ships (despite statements by Trump administration officials suggesting the contrary). If one accepts the Trump administration’s assertion that TdA’s drug smuggling is tantamount to an armed attack on the United States, then the drugs alleged to still be on the floating portion of the boat that the two survivors were trying to rightsize could perhaps themselves be seen as targetable in the same manner as weaponry. Alternatively, the drugs might be viewed as “revenue-generating objects” contributing financial support to TdA’s broader campaign, something that the United States has come to view as targetable under the laws of armed conflict, though not all countries (or legal scholars) agree.

Yet even if one accepts these positions, the second strike would have to comply with the requirement that whatever military advantage it provides must be proportionate to the harm it inflicts on civilians and other protected persons and objects, including those hors de combat. And the exact military advantage provided by pursuing the second strike is far from clear. Even if whatever drugs remained onboard the wrecked boat could reasonably be believed to have survived both the first strike and being subsequently submerged in water for 41 minutes, it’s not clear how one might reasonably expect them to return to the control of TdA, let alone move onward to the United States. Indeed, Bradley and Caine reportedly testified that the boat was believed to be inoperable and that the survivors were not believed to have had any communications equipment with which they could radio for rescue. Moreover, Secretary of State Marco Rubio previously asserted that interdiction was an available non-lethal alternative even before the first strike, providing another way of securing the same military advantage without killing the two hors de combat survivors. In this scenario, can one truly say that the marginal military advantage of destroying the drugs can reasonably be seen as outweighing the lives of the two survivors?

To be certain, these are the sorts of difficult operational decisions that military commanders must make, and there are good reasons that their determinations generally receive a substantial degree of deference when evaluated in hindsight. But this does not put them beyond question or reproach. Even taking such deference into account, the facts known about the second strike give ample reason to doubt whether the decision to pursue it comported with the international law of armed conflict, even as traditionally applied by the U.S. military. At a bare minimum, the question absolutely warrants continued investigation and scrutiny.

Moreover, this assessment still all relates to a framework designed for wartime. But few outside the Trump administration—and perhaps few within it—believe these military operations are actually taking place in the context of a real war. As a practical matter, the concerns presented by smugglers carrying narcotics are simply not the same as a soldier carrying a weapon. Yet the central premise of the legal justification the Trump administration has employed—from its invocation of the inherent right to self-defense, through the finding that the United States is in a NIAC, to the sorts of operational decisions governed by the jus in bello—deliberately conflates the two. This puts servicemembers in the unfair and immensely difficult position of being ordered to take action against the former on the basis of legal rules and policy guidelines designed for the latter.

The second Sept. 2 strike serves as a stark illustration of the pernicious effects this can have. For if an enemy soldier were caught in the same situation—or it were a member of al-Qaeda trying to rightsize a wrecked drug ship—they likely would never have been seen as a legitimate military target. But for the two survivors—who, like many of the others killed in the Trump administration’s campaign, may have simply been impoverished fishermen performing odd smuggling jobs with no specific animus towards the United States—a range of activities and objects bearing little resemblance to warfare somehow came to be treated as the equivalent of hostilities and weaponry. As a result, what may have been a simple attempt to survive ultimately cost them their lives.

Where Are the Lawyers?

Of course, all of this legal analysis presents an obvious question: where were the lawyers when the decision to pursue the second strike was made? And what advice did they give?

To be certain, foundational aspects of the Trump administration’s legal justification for its military campaign—its jus ad bellum argument, for example, and Trump’s determination that the United States was in a NIAC—would undoubtedly have been decided at the White House before any military operation was underway. Several of these legal positions have reportedly been memorialized in a classified Office of Legal Counsel opinion that would be binding on the rest of the executive branch, including the military. In this context, it’s not surprising that servicemembers—who can be criminally punished for disobeying lawful orders—might feel obligated to act pursuant to these legal positions, even if they do not personally find them credible. But no such opinion is likely to have reached the sorts of fact-specific targeting decisions made on Sept. 2.

Lawyers are traditionally integrated into every major operational decision the military makes, particularly as it relates to targeting decisions. Long-standing Defense Department policy and practice would generally require that a military lawyer with expertise in the law of war be consulted on the legality of any such attack. But under this administration, military lawyers (and their civilian Defense Department counterparts) are increasingly at risk of being either ignored or sidelined. One of President Trump’s earliest actions upon returning to the White House was to fire the top two uniformed lawyers of the armed forces. This came after reporting that Hegseth, whose own well-established contempt for military lawyers predates his time as Defense Secretary, warned members of Congress that military lawyers might serve as “roadblocks” to the president’s orders. Since then, analysts have been sounding the alarm about continued firings, as well as efforts to reassign (including to serve as immigration judges) and otherwise marginalize military lawyers (including by overhauling the Judge Advocate General (JAG) Corps and the military justice system). The intended effect of these measures, of course, isn’t just to purge the military of legal expertise, but to ensure that those who remain are pliant.

In this case, Bradley—who chose not to bring a lawyer when asked to testify before Congress about legal aspects of the military campaign this past October—claims that he consulted with military lawyers who confirmed that he could lawfully take the second strike. We don’t know what exact legal advice these lawyers gave, and it’s entirely possible that they advised against the maneuver, even if they might not have outright said it was unlawful. Regardless, if the legal advice that the head of SOCOM is receiving departs so clearly and unpersuasively from longstanding U.S. official views of what is and is not unlawful, then this alone warrants congressional attention. And there is good reason to believe that it may reflect a much more systemic and concerning state of affairs within the Defense Department.

That said, military lawyers are not the only bulwark against unlawful conduct by the military. All military personnel are duty-bound to disobey clearly unlawful orders pursuant to the Uniform Code of Military Justice and its implementing regulations, as several former members of the military and intelligence community recently argued. The obligation is nuanced—it is framed as an exception to the general duty to obey lawful orders—but it is unmistakable. The Law of War Manual speaks of “the requirement to refuse to comply with orders to commit law of war violations applies to order to perform conduct that is clearly illegal or orders that the subordinate knows, in fact, are illegal.” Likewise, the Manual for Courts-Martial, which provides that the otherwise-applicable presumption that orders are lawful and thus must be complied with “does not apply to a patently illegal order, such as one that directs the commission of a crime.”

The standard for being “patently illegal,” of course, is deliberately high. But it’s not a frivolous question in this case. After all, the Law of War Manual itself lists “orders to fire upon the shipwrecked” as an example of the type of orders that “would be clearly illegal.” As a result, it says, soldiers should “refuse to comply” with them.

No one should have any illusion, of course, that this is an easy step for any servicemember to take. This administration has made clear that defying or even questioning orders can cost servicemembers their careers and livelihoods; in the event of a court-martial, it could also cost them their liberty or even their lives during “time of war,” if their defense of the order being unlawful were to somehow fail. But this duty to question and potentially even disobey is an important one, if the U.S. military is going to live up to the standards of decency and humanity it has long set for itself. If we want servicemembers to be able to take this step, then the United States needs to provide them institutional support—and if it won’t come from within the executive branch (as is currently the case), then it needs to come from Congress.

Thus far, this Congress—in confirming nominees openly dismissive of legal and humanitarian considerations and sitting silent as the Trump administration has sidelined lawyers in order to evade potential legal barriers—has failed in this mission. But sorting through what actually happened in regard to the second Sept. 2 strike and, if necessary, ensuring accountability for those responsible could be a badly needed step back in the right direction by underscoring that there are still consequences for lawlessness.

***

For much of the world, the entirety of the Trump administration’s military campaign against alleged narcotics traffickers is a serious violation of international law. But even if one accepts every unorthodox element of the Trump administration’s international legal justification, the second strike pursued on Sept. 2 is still a problem. It’s not just in tension with longstanding Defense Department guidance on what is lawful and unlawful—it’s a paradigmatic example of the latter. If there are facts that vindicate the decision to pursue it, they are far from evident in the public record currently available. Until that changes, the issue demands further scrutiny. And only Congress has the authority and mandate—as well as the responsibility—to do so effectively.