The Year That Was (2022)

The issues—and Lawfare coverage—that kept our editors up at night in 2022.

As December draws to a close, we’ve reached the requisite moment to reflect on what happened in 2022. And although it may be cliche to say so, the answer from us at Lawfare is ... well, a lot.

We cover hard national security choices, and last year was full of them. Could the United States find a way forward one year after the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol attack? How should the world respond to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? Was U.S. law enforcement equipped to deal with the increasing threat of domestic extremism? Could law and policy keep up with emerging technologies? How should we as a society manage speech online? Would fighting climate change finally become a priority for the U.S. government? What should we make of the massive protests in Sri Lanka, Iran, China, Peru, and elsewhere? What are the appropriate limits on executive power, Congress, and the courts? And, echoing a still-unanswered question from Lawfare’s early days, how do we reckon with the injustices of Guantanamo, particularly now that we’ve passed the 20th anniversary of its opening?

We published hundreds of original articles and podcasts analyzing these and many more of the year’s most pressing national security issues. We compiled and summarized key primary source documents ranging from court decisions to inspector general reports to policy papers, including a comprehensive repository of documents and analysis relating to Jan. 6. And we also produced two narrative podcast series: Allies looks at how the United States failed its Afghan allies through the deeply flawed Special Immigrant Visa Program, and The Aftermath considers the government’s response to Jan. 6.

As ever, we benefited from indispensable work by outside contributors, without whom we could not bring you the breadth and depth of analysis Lawfare is known for. But to bring it all together—to present the big picture, to help evaluate those hard national security choices—we rely on our in-house team of experts.

So, in that spirit, I asked the Lawfare senior editorial team to write a few paragraphs to reflect on what happened in their areas of expertise in 2022, offering their own thoughts and a sampling of Lawfare’s coverage. We have Roger Parloff on the Jan. 6 criminal prosecutions, Quinta Jurecic and Molly Reynolds on the Jan. 6 committee, Tyler McBrien on climate security, Benjamin Wittes on the Mar-a-Lago investigation, Scott R. Anderson on developments in foreign relations and international law, Stephanie Pell on cyber issues, Alan Rozenshtein on social media and content moderation, Daniel Byman and J. Dana Stuster with an overview of the Lawfare Foreign Policy Essay series, and Saraphin Dhanani with a roundup of key Supreme Court national security cases.

And that is The Year That Was: 2022. We’ll see you next year.

– Natalie Orpett, Executive Editor

The Jan. 6 Criminal Prosecutions

As 2022 began, many wondered—including us—if Attorney General Merrick Garland’s Justice Department was taking the Capitol insurrection cases seriously enough and if his investigation would, as Garland promised on Jan. 5 of this year, truly reach those “at any level, whether they were present that day or were otherwise criminally responsible.” The first question was answered quickly and definitively. On Jan. 8, a grand jury charged 11 members of the Oath Keepers paramilitary group, including its founder, Elmer Stewart Rhodes III, with seditious conspiracy—the first use of that charge in more than a decade. By the end of the year, four defendants had pleaded guilty to that charge, while two more had been convicted of it after trial. I followed the Oath Keepers prosecution closely, live-tweeting all but about two hours of the 29-day trial from the courthouse media room by day, and analyzing the quality of the evidence and the plausibility of the verdict by night. I was also joined by Lawfare’s intrepid new courthouse reporter, Anna Bower, for opening statements.

The second question—whether the Justice Department would investigate the potential role of nonrioters in the insurrection, up to and including former President Trump—was more suspenseful. But as the House Select Committee on the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol exposed mounting evidence of criminal conduct at the highest levels—winning in March a civil court ruling that Trump likely committed crimes and then publicly eliciting, in June, powerful evidence of his corrupt state of mind on Jan. 6, through testimony like that of Cassidy Hutchinson—it gradually became clear that the Justice Department was hot on that trail as well, culminating in its appointment in November of Special Counsel Jack Smith to oversee that investigation. (Smith will also oversee the separate inquiry into Trump’s post-administration handling of top secret and presidential documents at Mar-a-Lago.)

At the same time, we covered the key factual and legal issues arising from the federal prosecutions of the more than 900 Jan. 6 rioters themselves, including the unusual wealth of digital evidence being brought to bear; the issue of whether judges are showing their political colors in their handling of these cases; the defendants’ recurring protestations that the District of Columbia juries are biased against Jan. 6 defendants; and the all-important question—still not definitively resolved—of whether the Department of Justice is properly using its most frequently invoked felony charge in these cases: corrupt obstruction of an official proceeding. The department has not only charged more than 290 defendants of violating that statute, already winning more than 70 convictions, but would likely invoke that law against any higher-echelon defendants who might eventually be charged, including the former president.

In the new year we will be covering another marquee seditious conspiracy trial, that of five top Proud Boy leaders, including the group’s former chairman, Enrique Tarrio. In addition, we will continue to follow the trial and appeal, respectively, in the complex contempt of Congress cases involving former White House advisers Peter Navarro and Steve Bannon. And, above all, we will be watching to see if Special Counsel Smith brings Jan. 6-related cases against nonrioters, including the former president.

– Roger Parloff, Senior Editor

The Jan. 6 Committee

It took the Jan. 6 committee a while to get the ball rolling on its public hearings this year: By April 2022, the panel had pushed back the start date for its hearings enough times that Molly Reynolds and I wondered in Lawfare just what was going on over on Capitol Hill. Once the committee finally got moving, though, its summer hearings set a rapid pace that rarely flagged. The investigators achieved an unusual feat: turning congressional hearings into a bona fide media event. Over the course of June and July—with one additional hearing in October—the public sessions showcased the committee’s ability to uncover genuinely new and surprising information about an insurrection so thoroughly documented that the Justice Department has collected 25 times more data about it than exists in the entire Library of Congress.

Most strikingly, surprise testimony by Cassidy Hutchinson, a former aide to Trump’s chief of staff, Mark Meadows, revealed a level of personal involvement by Trump in the events leading up to the Capitol riot that was sufficient to change the mind of my notoriously cantankerous Lawfare colleague Alan Rozenshtein as to whether Trump’s speech on the Ellipse that day constituted criminal incitement. As Bob Bauer wrote with Lawfare’s editor in chief, Benjamin Wittes, Hutchinson’s testimony also undermined a great deal of the assertions made by Trump’s defense counsel in the second impeachment about their client’s supposedly clean hands in relation to an armed insurrection.

When the hearings first began, I was doubtful that the committee would be able to unearth anything more damning than what was already obvious to anyone with an internet connection: that Trump had egged the rioters on and failed to stop them until well after they had already rampaged through the Capitol. My skepticism was misplaced.

Still, the single-minded focus of the committee’s final report on Trump’s personal culpability risks eliding—or flat-out rewriting—the many other factors that made Jan. 6 possible. In particular, the outright whitewashing of law enforcement and intelligence failures is a real disappointment. The Jan. 6 committee’s efforts over the past year and a half have made for an impressive and important performance. But at the last minute, it seems, the committee couldn’t quite stick the landing.

– Quinta Jurecic, Senior Editor

When the Jan. 6 committee finally began its principal series of hearings in June, I shared Quinta’s skepticism that the panel’s efforts would add much to the public’s understanding of what happened during the insurrection—not just because we already knew a lot about Trump’s role and the horrors faced by Capitol Police, the Metropolitan Police Department, and others, but also because I was skeptical that a contemporary congressional committee would be well positioned to hold Americans’ attention.

But I underestimated the committee on this front—largely because the committee’s approach to conducting the hearings departed so significantly from what we usually see in the House of Representatives. As Quinta and I wrote, the members of the committee, united behind a common purpose, displayed a remarkable degree of deference to one another and across party lines, up to and including having a member of the minority party, Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.), chair one of the panel’s sessions when chair Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.) was ill with COVID-19.

The committee certainly demonstrated what Congress is capable of when the incentives align for serious investigative work. But it also left many threads dangling when it wrapped up its work, and these remind us of the limits of a single, time-limited congressional investigation. Among the unresolved issues are, as Quinta and I discussed with Mike Stern on the Lawfare Podcast in January, whether and how a congressional committee can enforce subpoenas against its own members. Because House Republicans have promised to continue their own inquiry into the events of Jan. 6—including an investigation of the investigation itself—these questions may remain ripe in the year ahead.

– Molly Reynolds, Senior Editor

Climate Security

As managing editor, I try to make sure that Lawfare covers the most pressing national security issues of the day. It would be a dereliction of duty then to ignore climate change—arguably the most dire security threat of our time.

But don’t just take it from me. After frequently describing climate change as an “existential threat” since taking office, President Biden and members of his national security team made it official in October, giving climate change a leading role in its new U.S. National Security Strategy. As Karen Sokol pointed out in Lawfare, the strategy mentioned climate change 63 times, Russia 71 times, and China 55 times. “More important than the number of mentions, however, is how climate change is framed—as a top-tier threat on par with, and influenced by, geopolitical challenges from U.S. adversaries and competitors,” Sokol wrote. Perhaps the Biden administration took a page from the book of John Conger and Erin Sikorsky, who wrote for Lawfare earlier this year to propose some concrete climate security steps for the U.S. government.

Of course, many people, especially in the Global South, don’t need to read a 48-page PDF from the U.S. government to know that climate change is an existential threat. Climate change isn’t so much a future specter as a grim reality for many people who can see the immediate effects of flooding, droughts, and megastorms just outside their windows. Reckoning with the destruction already caused by climate change has put an emphasis on climate justice and the mechanisms for achieving it. This is an even more salient issue with emerging research demonstrating how specific emissions from one nation cause specific harms to another.

This year, our contributors asked tough questions on climate, and tried to answer them. “The impacts of climate change are not evenly distributed, and neither is the blame,” wrote Mark Nevitt in the aftermath of this year’s devastating floods in Pakistan. “Who should pay for Pakistan’s loss and damage? And what should be done to prevent and compensate for climatic harm disproportionately borne by developing nations?” As Sokol and Chris Callahan explained on the Lawfare Podcast, U.N. member states came together for the U.N. Climate Change Conference, or COP27, to discuss that very question. COP27 resulted in the creation of a loss and damage fund, a historic achievement, though one with its fair share of kinks to work out.

Before you accuse us of being all doom and gloom, I should highlight that Lawfare covered not only the threats but also some potential solutions. We drew lessons from another global disaster, the coronavirus pandemic, and explored the case for researching solar engineering in a two-part series. We even suggested a few ways to reduce emissions from the world’s largest institutional emitter of greenhouse gas emissions—the Pentagon. But the threat of climate change isn’t going away anytime soon, and neither will Lawfare’s coverage of it.

– Tyler McBrien, Managing Editor

The Mar-a-Lago Investigation

The FBI’s search of former President Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort took us, as it did almost everyone, completely by surprise. We got our bearings, analyzed the search warrant, and got to work. Jeh Johnson, former homeland security secretary and Pentagon general counsel, offered thoughts on the president’s declassification authority—given that Trump claimed to have declassified all of the material seized in the search. Scott R. Anderson wondered if it even mattered ultimately whether the seized material was classified given that “none of the criminal provisions listed in the search warrant hinge on whether the documents recovered at Mar-a-Lago are classified or not, making declassification he might have pursued largely irrelevant.” Heidi Kitrosser reflected on Trump’s potential liability under the Espionage Act, and Katie Kedian took on the larger regime of law governing classified material. Meanwhile, Alex Wellerstein spelled out the rules for declassification of nuclear secrets. Bob Bauer considered the discretionary questions associated with prosecuting the former president in a case like this one. And multiple contributors considered where the appropriate venue for a Mar-a-Lago trial would be, reaching somewhat different conclusions.

Then U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon threw everyone a curveball. She issued an order enjoining the Justice Department from using the seized material and appointing a special master to review it. Matthew Tokson analyzed the Trump arguments to Cannon and the relevant Fourth Amendment law. The Lawfare team cataloged everything—and there was a lot—wrong with the ruling and then the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit’s partial stay on the ruling. And Kel B. McClanahan commented on the appointment of Special Master Raymond Dearie.

The whole thing, of course, became moot when the Eleventh Circuit vacated Cannon’s entire order after a brutal oral argument before a conservative panel—leaving matters very much the way they were the day after the FBI executed the search warrant.

Except for one thing. In the meantime, Attorney General Merrick Garland turned the whole matter over to Special Counsel Jack Smith.

— Benjamin Wittes, Editor in Chief

Foreign Relations and International Law

This has been a watershed year for foreign relations and international law of a type not seen in decades. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and U.S. tensions with China have triggered important new questions about the international system and the United States’ relationship with it. And as policymakers have wrestled with these unprecedented global challenges, they and their lawyers have developed new and innovative tools with which to respond—some of which may have broader ramifications for years to come.

Arguably, the year’s most important developments arose from the war in Ukraine. For some, Russia’s invasion—which openly flaunted the most foundational principle of the postwar era: the prohibition on conquest by military force—initially seemed like it might be the death knell of the international system. Instead, that system has not just persevered but begun to evolve in response. International law has played a central role in determining how far the United States and its allies can go in aiding Ukraine without unduly inviting war with Russia. International institutions have begun to adapt, with the United States and other major powers openly endorsing U.N. Security Council reform even as international tribunals have embraced innovative theories of jurisdiction to try and hold Russia accountable for its crimes. The United States and other states that have historically been skeptical of these institutions are increasingly embracing them, and proposals to finally bring those states’ domestic legal systems into alignment with their international legal obligations are finally bearing fruit. Long-standing treaties are newly relevant as Europe wrestles with this new conflict; not the least of these is NATO’s foundational North Atlantic Treaty, whose obligations are playing a central role in shaping the response to Russia’s aggression. These remain perilous times, with a major conflict between two nuclear powers closer than it’s been in decades. But instead of ushering in the end of the international system, the Ukraine conflict may help make it newly relevant.

Competition with China, meanwhile, has taken a somewhat more subtle if no less important form. This past year marked the consolidation of Xi Jinping’s rule in China and the continuation of the Chinese government’s efforts to assert ever greater technological control over its citizens. Tensions over Taiwan, human rights, and other issues in turn put new strain on China’s relationship with the United States. While neither country seems inclined toward direct conflict, the continued deterioration in relations has left the two major powers searching for rules of the road that might help manage the risk of conflict between them. The Biden administration sought out new ways to put pressure on China and to bolster the United States’ own ability to compete with China in areas ranging from telecommunications to semiconductor manufacturing.

A major issue in both major power competitions—and a main focus of mine this year—has been economic statecraft, specifically a new and rapidly evolving set of tools into which major powers are channeling their competition. Following the invasion of Ukraine, the United States and its allies leveled an unprecedented array of sanctions against Russia and its ally Belarus, including a freeze of its foreign-held central bank assets and novel export control measures intended to hinder Russia’s development and limit its access to critical strategic technologies for years to come. The former has in turn triggered debates as to whether frozen funds could be used to compensate Ukraine for Russia’s crimes consistent with domestic and international law. China, meanwhile, has found itself on the wrong end of similar measures in its competition with the United States over strategic technologies. All told, in our new era of major power competition, these sorts of innovative economic measures seem likely to become an increasingly important part of countries’ foreign policy toolkits.

Yet this new era of major power competition does not mean old challenges have gone away. Even as the United States has attempted to shift its focus to China and Russia, it has still had to deal with the lingering legacy of those issues that have been the focus of U.S. foreign policy for much of the past two decades. In Afghanistan, this meant trying to deal with the immense humanitarian fallout from last year’s U.S. military withdrawal and subsequent collapse of the Afghan government, as well as lingering issues such as claims against Afghanistan’s central bank assets, how to engage with the Taliban regime now in control of the country, and the best way to advance U.S. counterterrorism policies there absent partners on the ground. In Iraq, the Biden administration continued to work on striking the right balance of engagement amid Iraq’s ongoing domestic political crisis—even as Congress wrestled with the legal legacy of the U.S.-led invasion that it authorized more than 20 years earlier. Elsewhere around the world, various policies shaped over the prior two decades continued to combat the specter of global terrorist threats in sometimes new and unexpected ways, even as our traditional terrorist rivals underwent their own major changes.

In sum, 2022 seems likely to be remembered as a threshold year: one in which the new priorities that will shape international relations (and the legal relationships that intersect with them) for years to come came sharply into focus, even as we remained anchored in our past. What’s next remains to be seen, but the year’s events give some hint of where things may lead.

– Scott R. Anderson, Senior Editor

Cyber

I have to cringe a bit whenever I’m asked the question “What’s interesting in cyber?” The online version of Webster’s Dictionary still lists “cyber” as an adjective, not a noun, and, as Greg Conti and David Raymond acknowledge in the “Hacker’s Apology” from their book, the term “cyber” “chafes at some, especially in the hacker and information security communities.” But as Conti and Raymond correctly observe, at least in the world of the military and government, the battle over use of the word “cyber” has been lost—for better or worse, it has been fully integrated into these communities.

So for lack of a different sufficiently broad term, Lawfare covered quite a number of “cyber” issues this year, only some of which I’ll mention here. The war between Russia and Ukraine drew attention to the topic of cyberwarfare. Just prior to the start of the war, Russia was engaging in offensive cyber operations against Ukrainian government websites and systems. While Russia’s intentions are now clearer in hindsight, the import and meaning of those malicious cyber operations was not clear at the time. Indeed, interpreting state intentions in cyberspace is an ongoing challenge in times of peace and when states are on the precipice of war.

Throughout the course of the conflict, however, observers have questioned and debated why Russia has not employed more destructive cyberattacks against Ukraine. But as Thomas Rid has ironically quipped, cyberwar is here and significant cyberattacks are occurring, but they are more covert and insidious in nature than some observers expected. Examining the conflict at a later point in time, Susan Landau also explained how Russia is incorporating cyber and information warfare into the war against Ukraine in ways that may not be readily apparent.

A sizable portion of the public’s vision into and understanding of the kinds of offensive cyber operations Russia is deploying against Ukraine comes from Microsoft’s own reporting. Microsoft and a number of other private-sector companies have emerged as integral players in Ukraine’s cyber defense. Unique insights from private companies like Microsoft—which own and operate much of cyberspace—are central to the kind of public-private partnership that National Cyber Director Chris Inglis believes is critical to strong cybersecurity and cyber defense. But sustaining that kind of partnership, which raises certain concerns, and the sharing of private-sector data that it entails requires trust. The government will need to be careful not to abuse that trust.

Researchers will be studying the details, scope, and intensity of cyber conflict that emerges from the war between Russia and Ukraine for years to come. And Lawfare contributors will continue to examine cyber-related issues arising out of this war, like the implications of patriotic hacking in the context of armed conflict.

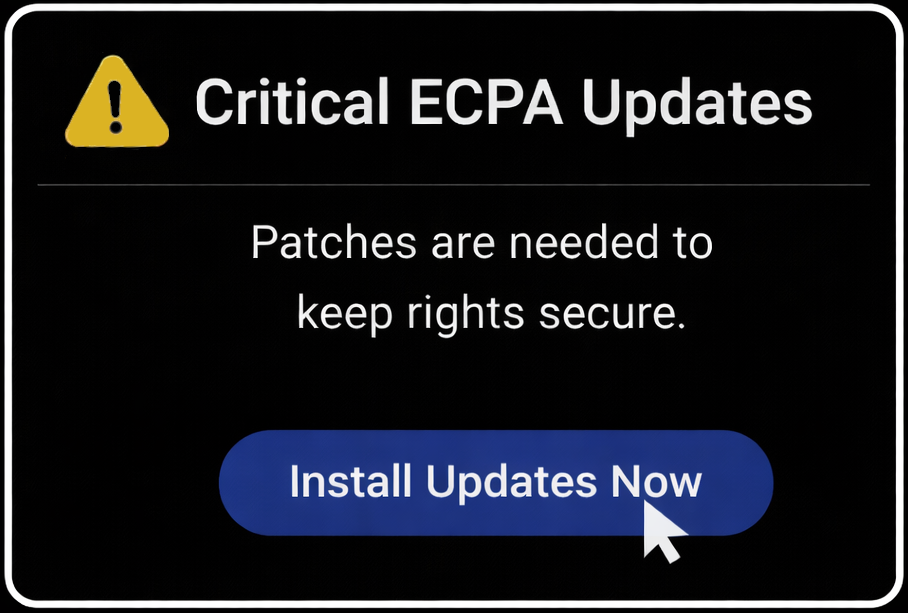

Extending the term “cyber” to apply to issues surrounding electronic surveillance and privacy, at least for the purpose of this article, I would predict that one of the most heated, difficult surveillance discussions in 2023 will involve the reauthorization of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), which is expiring at the end of 2023. Adam Klein notes that Section 702 is the National Security Agency’s “most significant tool,” providing it with “[i]rreplacable insight.” The Biden administration will not want to let this authority expire, although, as Klein explains, the politics will be challenging.

From my time spent on Capitol Hill as the lead Democratic counsel on Patriot Act reauthorization for the House Judiciary Committee in 2009, one thing I know about the expiration of surveillance authorities is that the reauthorization process can involve more than just the particular authority that is sunsetting. Beyond other aspects of FISA that Klein suggests could be targeted for reform, there will likely be additional calls for surveillance reform outside of FISA. While a lot can happen in a year’s time, and priorities can certainly change, one area that I think could be at the top of the reform list for civil society and some congressional offices is the regulation of the government’s purchase of private-sector data. There are problematic scenarios and other circumstances that are exacerbated by the government’s ability to purchase private-sector data that it would otherwise need a warrant to compel. The Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, or some similarly focused bill yet to be written, could provide a vehicle for ensuring that the Fourth Amendment continues to provide a degree of protection for categories of data where courts recognize that there are legitimate Fourth Amendment interests.

– Stephanie Pell, Senior Editor

Social Media and Content Moderation

This year saw three major content moderation stories. First, Texas and Florida passed laws limiting the extent to which large social media platforms can moderate content. The Florida law, which was enjoined by a district court in 2021, was held by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit to be an unconstitutional infringement on the platforms’ First Amendment rights, a decision whose breadth I criticized as an example of “First Amendment absolutism” (but that others defended as putting forward a “consumer protection approach to content moderation”). The Florida law also imposed a variety of transparency mandates, whose constitutionality Lawfare contributors also analyzed.

A few months after the Eleventh Circuit struck down the Florida law, the Fifth Circuit issued its opinion upholding the Texas law. I was sharply critical of the opinion, calling it a “crude hack-and-slash job” that was its own example of First Amendment absolutism, albeit from the other direction.

Second, Elon Musk purchased Twitter. Musk’s controversial decisions—some might say antics, including replatforming former President Donald Trump—have led many to abandon the platform for other options, most notably Mastodon, a decentralized alternative and part of the emerging “Fediverse.”

And third, the Supreme Court took up two cases that have the potential to radically reshape the Internet. In Gonzalez v. Google and Twitter v. Taamneh, the Court will decide whether Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 immunizes platforms from harm caused by their algorithmic amplification of terrorist content. Whatever the Court decides, Congress will no doubt continue to debate reforms to the controversial law, and Lawfare’s Quinta Jurecic offered a retrospective analysis of what happened the last time Congress amended Section 230.

Outside of these three stories, Lawfare continued its coverage of content moderation, including discussions of the use of international and human rights law, attempts by the European Union to require more moderation of harmful content, and country-specific issues in Ukraine, Israel and Palestine, and New Zealand.

– Alan Rozenshtein, Senior Editor and Book Review Editor

Lawfare’s Foreign Policy Essay Series

The Foreign Policy Essay, our weekly spotlight on national security and broader U.S. foreign policy issues, covered a range of topics this year—from growing concerns about China’s role in international politics and how the United States should respond to the currents of diverse violent extremist ideologies in the United States and around the world. But the war in Ukraine received the most attention. Although much work over the past year in various foreign policy and news outlets accurately assessed the Russian invasion as a disaster, Foreign Policy Essay contributors provided thoughtful analysis on why this was the case. They took on difficult questions and offered compelling answers for why Russia invaded in February, why that escalation has gone so poorly, how Ukraine defied expectations, and what consequences the war will have—for Eastern Europe and for U.S. allies in general, but also for the dynamics of great power competition.

Even before the invasion, when U.S. defense officials first started warning of a Russian military buildup, Foreign Policy Essay contributors warned that escalation was likely because Russia’s gray zone conflict in Eastern Ukraine had failed to meet its strategic objectives and even backfired by pushing Kyiv closer to the United States and Western Europe. When Russia invaded, it did so based on overly optimistic assessments of Ukrainians’ willingness to accept an occupation, a failure to account for the strength of Ukrainians’ will to fight—or the weakness of Russian forces’ own resolve and training. Once the fighting started, Russia was slow to learn from its mistakes, including some that it could have anticipated had it paid closer attention to the U.S. experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan. Contributors warned that now and in the future, Russia’s miscalculation will affect its capacity to stay as engaged as it has been around the world, particularly in Africa, and will make it more reliant on Kremlin-backed military contractors like the Wagner Group.

Many contributors looked beyond the immediate crisis to consider the medium- and long-term consequences of Russia’s aggressive policy, particularly for the United States and its NATO allies. Contributors warned that the war could turn into a proxy war that draws other countries into a grinding, indefinite stalemate. But the United States and its European partners largely seem to have recognized Russia’s actions as a moment of “strategic clarity” and are preparing for long-term support to Ukraine. Germany even announced plans to increase defense spending and may, in time, become a bigger player in European security.

But the consequences of the war extend far beyond the next few months in Eastern Europe. Contributors argued that the conflict will unify Europe and isolate Russia—which could make it even more desperate and unpredictable—and that NATO should remain focused on the threat of great power revisionism, from Moscow to Beijing. For the United States, lessons learned from the fighting in Ukraine should also shape procurement, training, and doctrine.

— Dan Byman, Foreign Policy Editor, and J. Dana Stuster, Deputy Foreign Policy Editor

Supreme Court and Major National Security Cases Roundup

This year, Dobbs v. Jackson and other high-profile cases underlined the reality that justices are deciding cases largely on ideological lines. With a conservative majority on the bench, decisions led to an erosion of the powers of the administrative state and a decline in civil rights protections in cases where national security was at issue.

The new year started with a coronavirus vaccine case, in which the Supreme Court stayed a workplace safety rule—known colloquially as “vaccine-or-test”—issued by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Lawfare’s continued coverage of the coronavirus and its fallout included this development, with one of our contributors arguing that the decision was a “setback” for the Biden administration’s pandemic response strategy and “signal[ed] [the Court’s] willingness to scrutinize an agency’s statutory authority.” The case became a harbinger of how the Court would rule on future administrative law cases, “as long-running battles about the limits on what Congress may permissibly delegate … and other forms of deference [to an agency’s rule] manifest themselves before a Supreme Court with members with conservative perspectives.”

This trend continued this summer in the case of West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In a 6-3 decision, the Court limited the EPA’s authority under the Clean Power Plan to regulate how power is generated to meet carbon reduction goals. Our contributors analyzed the case and its broader implications. One argued that the “real target” of this opinion “was the authority of regulatory agencies [and the] possibility of curtailing in the future the regulatory authority of other agencies such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau, and the Consumer Product Safety Commission.” The United States’ highest court, he said, is swimming against the current on “addressing the issue that will determine the quality of life of our children and grandchildren as well as the stability of the planet’s life-support systems.”

Elsewhere, the Supreme Court reined in the powers of the executive and federal courts. The justices (save for Justice Clarence Thomas) denied President Trump’s motion to block the National Archives from disclosing correspondence and documents. In doing so, it left untouched the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit’s holding: In such an “extraordinary” situation where there was a “clear and apparent effort to subvert the Constitution,” asserting executive privilege will not hold water when weighed against Congress’s need to investigate the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. And in the case of Patel v. Garland, the Court held 5-4 that federal courts were prevented from reviewing factual findings of an immigration official’s determination of whether noncitizens would be deported or granted permission to remain in the U.S.

But the Supreme Court broke away from advancing the small-government cause when it embraced a maximalist view of congressional war powers under Article I of the Constitution. The case, known as Torres v. Texas Dep’t of Public Safety, gave Congress plenary powers to authorize private suits against nonconsenting states when states impeded Congress’s powers to raise and support a military. The Supreme Court concluded that state sovereign immunity was subject to structural waiver because on this issue, the government’s powers are “complete in itself,” leaving no residual powers to the states.

Finally, the tension between citizens’ civil liberties interests and the government’s national security interests took center stage this year. A blow to police accountability came in the case of Egbert v. Boule, where the plaintiff filed a Bivens lawsuit against a U.S. Customs and Border Protection agent for violating his First and Fourth Amendment rights under the U.S. Constitution. In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court held that the plaintiff was not entitled to seek money damages for the harm caused by the agent’s excessive force and retaliation, in part because the claims raised national security concerns that the Court hesitated to opine on. Elsewhere, the Supreme Court buttressed the federal government’s state secrets privilege in not one, but two cases: United States v. Husayn (Zubaydah) and FBI v. Fazaga. In the former case, the Supreme Court held that state secrets that had been leaked, or otherwise become publicly available, did not constitute a de facto waiver of this privilege. In effect, the Court closed the door for civil suits against the government for its national security activities that had become public. And in the Fazaga case, the Supreme Court similarly held that plaintiffs could not bring lawsuits against law enforcement for their illegal electronic surveillance.

Looking ahead, we may see the content moderation case of NetChoice v. Moody creep its way up to the Supreme Court. The Florida attorney general petitioned the Supreme Court to weigh in on a Florida state law, SB 7072, that orders social media platforms to “host certain users, carry certain posts, … moderate content in a consistent manner,” and impose transparency rules. If the Supreme Court takes the case, it could altogether reshape digital speech rights and content moderation in the United States.

— Saraphin Dhanani, Legal Fellow